As the classic image of Totoro against a bright blue backdrop glowed on the screen, I couldn’t help but be reminded that “The Boy and the Heron” was the last movie that Hayao Miyazaki — co-founder and director of Studio Ghibli — would ever create. He told his producer that this film would be his last. Miyazaki won his first Golden Globe at age 83 for “The Boy and the Heron,” on Jan. 7.

“The Boy and the Heron” is an encapsulation of Miyazaki’s life and career. Rather than creating a character whose journey closely follows his life, Miyazaki projects himself, his thoughts and his experiences onto several characters, illustrating different stages of his life and the conflicting ideas and philosophies he holds. The semi-autobiographical film follows Mahito, a young boy growing up in early 1940s wartime Japan. Right at the beginning of the story, Mahito loses his mother to a fire in a hospital caused by a bomb. As he runs through the burning city towards the hospital, the animation style is distinctly different from the rest of the film, taking on a disorienting and chaotic quality that reflects Mahito’s desperation and seems new and unique among Miyazaki’s animations. This scene is personal to Miyazaki, whose earliest childhood memories are of bombed, burning cities, according to IndieWire.

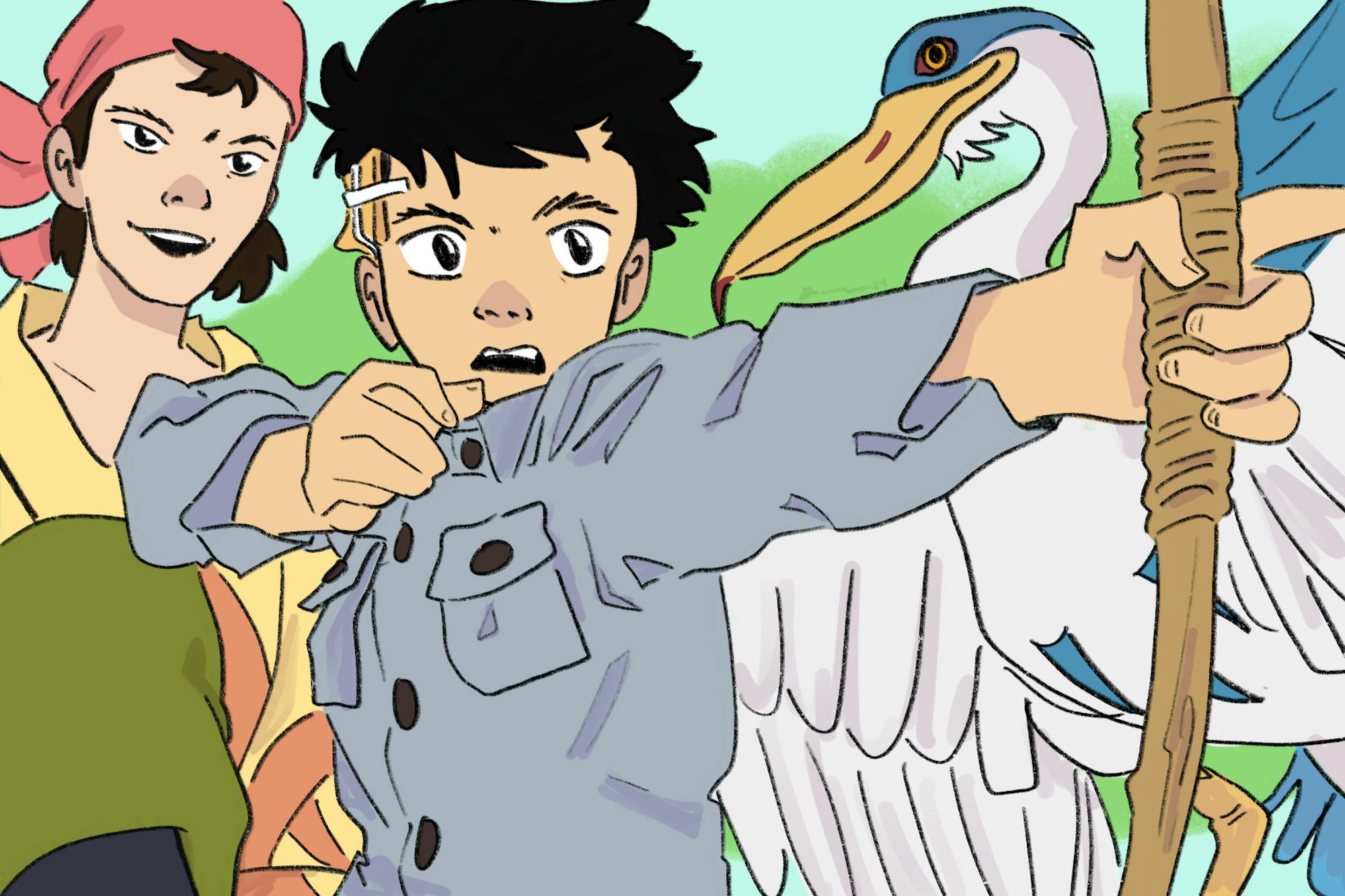

After the fire, Mahito and his father move in with Mahito’s maternal aunt, who his father has since married, in the Japanese countryside. The house, also inhabited by several old ladies who seem motivated by their desire for cigarettes, sits next to a lake, with a dilapidated, old, stone tower nearby. There, while struggling with his grief and not accepting his aunt as his stepmother, Mahito encounters a mysterious gray heron who, through a series of strange events, guides Mahito to a tower that takes him to a world populated by the living, the dead and the fantastical. The strange world he enters contains creatures ranging from the adorable Warawara to human-eating, anthropomorphic parakeets. It is kept in balance by his grand-uncle, who strives to create a perfect world that is “free from malice.” His grand-uncle wants Mahito to continue his work.

In the real world, this malice is embodied by the violent conflict of World War II and Mahito’s experience being bullied at school, which pushes him to injure himself with a rock to avoid going back. In the fantasy world, malice manifests itself in the pelicans that prey on the Warawara and in the monstrous, human-eating parakeets. Mahito’s grand-uncle sees the predator-prey dynamic between the parakeets and humans, as well as the pelicans and the Warawara, as a form of evil, reflecting his belief that death in itself, even as a natural part of the cycle of life, is inherently negative.

The pelicans and the Warawara also speak to environmental issues caused by excessive human manipulation of the natural world, demonstrating the harmful impact of introducing a species from one ecosystem into another — the pelicans from the “real world” into the “fantasy world.” Studio Ghibli has never shied away from environmental issues and interactions between humans and nature: “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind” and “Princess Mononoke” are some of the best examples of this.

Despite his grand-uncle’s need for a successor, Mahito chooses to go back to his world, having seen, throughout his journey, that it was impossible to create a truly perfect world. He wants to return to the world he knows, in spite of its violence, grief and pain. In many ways, the grand-uncle’s desire for a world without evil and Mahito’s understanding that there is beauty and joy in the world and in humans despite their imperfections and pain reflects Miyazaki’s personal philosophies. Miyazaki reveals that because of our inherent imperfections, humans are only capable of creating a beautiful world, not a truly perfect one.

Watching the movie brought back memories of some of the first movies I’d watched by the studio when I was four or five years old, like “My Neighbor Totoro,” “Howl’s Moving Castle” and “Ponyo.” “The Boy and the Heron” brings classic elements of Miyazaki’s filmmaking style — beautiful poster-paint backgrounds and fantastical creatures, to name a few — and even parallels some scenes and elements of his other films. One scene, in which Mahito finds a tunnel-like path into the woods that leads him to the tower, looks almost identical to a similar scene in “My Neighbor Totoro.” The shadowy figures Mahito encounters are reminiscent of similar beings in “Spirited Away,” and the strange world dominated by the sea with prehistoric-looking creatures feels very “Ponyo”-esque.

While the animation of the film is beautiful — possibly the best of his career — the plot can be hard to follow. It is not a movie designed for people who need everything to be resolved in a way that makes sense; it raises more questions than it answers through its exploration of grief, mortality and the instability and beauty of the world. Viewers might need to watch it twice, or several times, and do a good bit of thinking afterward to digest it fully, but all great works of art reveal more meaning the more you engage with them. It’s the kind of movie that leaves viewers feeling slightly dazed after leaving the theater, in a “what did I just watch?” kind of way.

“The Boy and the Heron” has been criticized for its sometimes awkward pacing and the constant introduction of new and unresolved plot points, without much time and space for viewers to contemplate and understand them. I disagree: Whether intentional or not, the film’s chaos is enticing and immersive, leaving viewers with questions about humanity and the world at large. Miyazaki seems to use the characters and his classic, world-building style to immerse us into his mind — in all of its complexity and fantasy.

Rating: ★★★★☆