The hurried scratching of pencils on paper and the monotonous ticking of an analog clock, an agonizing reminder of fleeting time, are the only perceptible sounds in the eerily silent SAT testing room. This classroom might ordinarily facilitate lively academic discussions or debates, but in this instance, it is a vacuum devoid of intellectual curiosity and engagement. Even recounting my own harrowing experiences with standardized testing is enough to put me on edge, a sentiment often echoed by my peers. The grueling process necessary to succeed on behemoth tests left me worn and once led me to naively conclude, as many high school students have, that standardized testing should be scrubbed from the college admissions process.

Until recently, I advocated strongly for the permanent adoption of test-optional admissions and even went so far as to support test-blind admissions. However, empirical evidence does not always echo our feelings — especially about something like test-taking — and what we want is not always what’s good for us. The reality is that standardized tests are actually useful tools for admissions.

A recently published New York Times article by David Leonhardt — which draws on research from Dartmouth’s own Richard S. Braddock 1963 economics professor Bruce Sacerdote ’90 and associate sociology professor Michele Tine — highlights evidence that standardized test scores are better indicators of predicting college grades, chances of graduation and post-college success than high school grades and may also increase diversity on college campuses.

Experts from top institutions support standardized tests’ ability to predict success in college and beyond. Brown University president Christina Paxson said in an alumni magazine issue last year that “these tests do reveal useful information about whether students will, on average, be academically successful.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology Dean of Admissions Stu Schmill, who recently reinstated standardized test requirements there, echoed Paxson’s assertion that test scores are superior predictors of academic success. He explained in an MIT admissions blog that test scores are especially good predictors of success due to “the centrality of mathematics” in the MIT curriculum.

Considering the stark contrast between Brown’s open curriculum model and MIT’s rigorous, math-focused General Institute Requirements, this combination of testimonies lends credence to the overall assumption that standardized tests bring stronger candidates to educational institutions. Dartmouth, which prides itself on a liberal arts approach to education, falls somewhere between Brown’s open curriculum and MIT’s more structured model and may also find reinstating testing requirements beneficial in future admissions cycles.

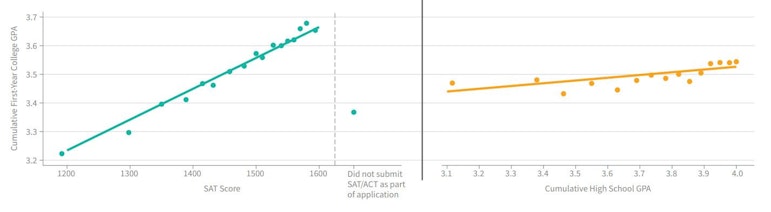

A recently released report by Opportunity Insights, a research group led by Harvard economics professors Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren and John Friedman, demonstrated the contrast between standardized test scores and high school grades as predictors of college success.

Courtesy of Opportunity Insights

As depicted in the above graphs, SAT scores are strongly correlated with first-year college GPA, whereas high school GPA had only limited ability to predict success. This revelation may come as an unwelcome and jarring surprise. It is difficult to understand that an impersonal, mass-distributed test can provide insight into a student’s success in all college courses, which vary significantly in forms of instruction and material. However, whether or not researchers can definitively link specific SAT-tested skills to success in the classroom, we cannot argue with the overall empirical evidence.

Given the Supreme Court’s ruling on affirmative action, the second and most critical benefit of standardized tests is their ability to promote diversity on college and university campuses, despite the frequent allegations that they do the opposite. As journalist David Leonhardt explains, standardized testing has become a highly politicized subject, with many progressives expressing concern about score disparities by race and class. The COVID-19 pandemic limited access to these tests for many applicants, giving institutions like Dartmouth the opportunity to shift to test-optional models. Another 2023 report by Opportunity Insights found that children of the wealthiest 1% of Americans were 13 times more likely to score a 1300 or higher on the SAT than children of lower-income families. The report also highlights the disparities between high and low-income children in their readiness to learn, health and ability to sit and listen. These factors set trajectories for a child’s education at early ages.

David Deming of Opportunity Insights specifies that many more considerable disparities emerge outside of the classroom, as low-income children's access to educational opportunities shrinks relative to their higher-income counterparts. This critical distinction between inequality inside and outside of the classroom affirms the necessity of standardized testing in college admissions. Opponents of these tests argue that, with their reinstatement, campus diversity will decrease due to income-based advantages, such as private test tutoring. Yet, eliminating tests implies that admissions officers must shift towards emphasizing extracurricular activities outside the classroom instead, most of which cater to higher-income families.

Leonhardt highlights examples such as traveling sports teams, private music lessons and access to private college counselors as application boosters, which are widely unavailable to underprivileged students. Schmill explains that MIT uses standardized test scores to indicate promising students from less advantaged backgrounds. With a lack of access to impressive extracurriculars and private assistance from admissions professionals, standardized test scores may be the saving grace of underprivileged students with extreme potential.

Dartmouth lags behind its Ivy League counterparts in racial and ethnic diversity. Among the Ivies, Dartmouth has the highest percentage of white students in its student body at 50% of all students, and only 5% and 14% of Dartmouth students are Black or Asian, respectively. It is no secret that these racial and ethnic disparities correlate with socioeconomic status, with 21% of Dartmouth students coming from the top 1% — the highest among the Ivy Plus schools — and only 2.6% of students coming from the bottom 20% — among the lowest in the Ivy Plus group. Reinstating standardized testing as a mandatory part of admissions at Dartmouth may be one of the key factors in transforming this school into a more racially and socioeconomically diverse institution.

Opinion articles represent the views of their author(s), which are not necessarily those of The Dartmouth.