On Sept. 20, Princeton University professor of African American studies Dr. Ruha Benjamin delivered the inaugural Susan and James Wright Lecture on Computation and Just Communities. The lecture, titled “Utopia, Dystopia, or… Ustopia?,” was held in Oopik Auditorium and attended by about 250 people, according to Wright Center manager Christine Ellen.

The lecture was the first to be sponsored by the Wright Center, founded in 2020 in honor of President emeritus James Wright and Susan DeBevoise Wright. According to their website, the center seeks to understand the impact of computational innovations on social and civil issues.

In her lecture, Benjamin spoke about two stories behind technological progress — a “techno-dystopian” narrative where technology turns against humans and a “techno-utopian” narrative where technology solves all of our problems. Both share a “techno-deterministic” logic, which discounts the importance of human agency in deciding the future impacts of technology, according to Benjamin. She said it is time to “pull back the screen” on technological progress and think about the motivations behind these innovations.

Benjamin also spoke about the concept of “discriminatory design,” or designs that discriminate against specific groups of people, using an example of a park bench with built-in armrests to prevent homeless people from laying across it. The bench is an example of how design and innovation can be used to exclude people while doing nothing to address the causes of problems, like the housing crisis, according to Benjamin. She said a bench with a rainbow pattern and the same armrests is an example of “predatory inclusion,” which are cosmetic changes that are only inclusive at the surface level.

“It’s not a quick fix, [to] just throw technology [at a problem],” Benjamin said. “If we’re going to use these types of [digital] tools, why are we pointing them at the most vulnerable?”

Benjamin added that technological innovations can improve convenience for certain groups at the cost of other groups. For example, she said she could order a steaming hot bowl of ramen on her phone to be ready outside as soon as the lecture was over. That would be convenient for her, but it would not take into consideration the conditions of the people who made the experience convenient, she added.

“The fantasy of some is a nightmare of others,” she said.

According to Benjamin, digital innovations like AI are often subject to bias, introducing the concept of the “new Jim Code,” — a term she said she coined in reference to the Jim Crow era. Jim Code, as Benjamin defined it, occurs when discriminatory design is built into new technical innovations in a way that excludes or harms certain groups while appearing to improve efficiency and convenience.

Benjamin emphasized the importance of learning from history, particularly the moments in history when “scientific progress” was used to justify racism and oppression. Benjamin said that the increased public focus on “deep learning,” but said that computational depth without social and historical depth is not in fact deep learning but “superficial learning.”

“In many ways we’re living in someone else’s imagination,” Benjamin said. “It’s not just the impacts of these tools that we need to be concerned about, but the inputs.”

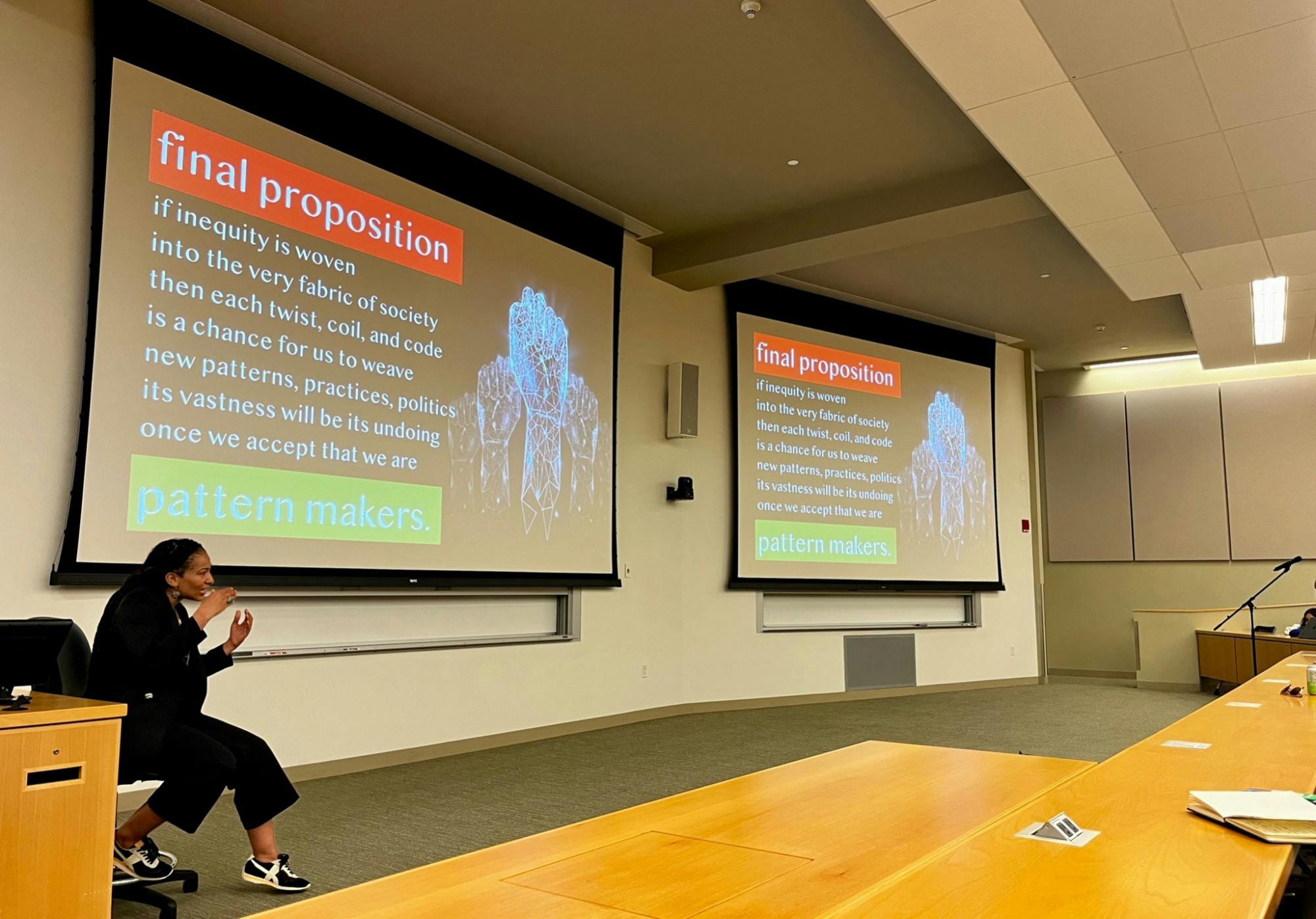

Benjamin concluded her lecture by laying out several areas in which she said progress could be made in terms of ensuring that technological progress has truly equitable outcomes. She highlighted initiatives including the Consentful Tech Project and the Data Nutrition Project, which both advocate for more careful data and information use by AI models to prevent biased data being built into these new technologies.

Engineering professor and co-director of the Design Initiative at Dartmouth Eugene Korsunskiy said Benjamin’s lecture impacted the way he thought about his own teaching.

“It’s really important that students are equipped with conceptual and critical tools, and they know how to use the power they have as designers and engineers,” Korsunskiy said. “It’s not enough to teach students to question and point out the flaws without being able to create better possibilities.”

Film and Media studies professor Jacqueline Wernimont also attended the lecture and said she appreciated the focus on small-scale practical innovations that make a more equitable world. Wernimont added that she is teaching Benjamin’s 2022 book, “Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want” in FILM 48.04: “Social Justice and Computing.”

“Dr. Benjamin’s work is super valuable to me,” Wernimont said. “She asks questions about how we build the world we want.”

Ellen said that she appreciated how Benjamin engaged with students throughout the talk.

“[It was] as if each student was alone in a room with her having a chat,” Ellen said. “She embodied what the Wright Center is all about.”

Benjamin ultimately urged the audience to both learn from past generations and adapt to current contexts.

“The durability of racism … is directly tied to a belief about its inevitability in biology, “ she said. “If science and scientists were so pivotal in creating the problem [of racism], we’re also responsible for addressing it.”