On June 16, I departed for my study abroad program — the LSA in Santander, Spain — with Dartmouth. When I left, my sister sent me an article in The New Yorker called “The Case Against Travel” by Agnes Callard. It describes time abroad as a manner of “obscuring from view the certainty of annihilation” and tricking oneself into believing we are growing. After reading this piece — which describes travel as “preparation for death” — I was suddenly self-conscious. I hugged my parents goodbye and boarded the plane for Madrid.

In the air, I tried to vindicate myself: I was going to Spain to study and learn a language, not remain a passive outsider. But it didn’t make me feel better that I had recently bought myself a Nikon FE from 1982. The camera bag slung around my neck reminded me that I was like every traveler Callard identified — motivated by “trinkets and photos.”

The camera is the quintessential tool of the distanced tourist. In the book “La Furia de las Imágenes,” Spanish photographer Joan Fontcuberta argues that digital photography and social media have transformed the way we use cameras. When we snap a selfie in front of a landmark, we are only asserting our existence, reminding ourselves, “I was there.” Our era of photography is premised on solipsism.

It’s true that at the Alhambra, everyone lines up behind each other to take the same photo of the Nasrid Palace. But, viewing everything through a camera lens, how could I pretend to be distinct from this alienating lack of looking? I could eavesdrop on conversations and (to Callard’s point) try to sniff out the “Spanishness” of those around me — but I would always be a girl from New York looking through her camera.

This essay was born in response to these anxieties. These photos are moments of quietude or intimacy, when I felt exposed to the “real” Spain (whatever that means).

I took this first photo in Sevilla during a week of solo travel. I was lonely, and it was 105 degrees, so I sat down under a large shade installation and ate ham I bought from the grocery store. I drank water copiously and admired the skateboarders who could bear to wear jeans in the heat.

Stefano, a 23-year-old photographer from Lima, Peru, approached me while I was watching. He charmed with kickflips and the drawings of ghosts up his forearms. Despite the fact that he spoke English, he spoke to me in Spanish — I don’t really know why. I never understood why he was living in Sevilla, but I knew that he wanted to leave. He missed his father, and this didn’t feel like home. In my own isolation, I agreed.

He had an old friend named Pedro, who zipped around on an electric scooter. Before benches lined the plaza, Pedro could scoot up the wall and do tricks, Stefano told me. New seating was another way tourists took over their skate park, along with the Instagrammable “I Love Sevilla” sign and an aquarium. I pretended not to recognize the irony of him complaining about tourists to me.

This is Esperanza, the woman I lived with in Santander. She is a grandmother with bright red hair and this little backyard where we ate lunch. Weeds grew through cracks in the cement, and the walls were covered in friendly graffiti: “Hola,” a smiley face and “paz.”

Esperanza and I were a good match. We talked about politics and Spain, the subjunctive tense and Vega, her two-year-old granddaughter. I realized over time that her constant acts of giving — lending me a bed, a key, a sandwich — were characteristic of her generous nature: Vega stayed for long stretches of time with us while Esperanza’s daughter went on vacation. Esperanza hemmed the pants of her niece’s friend. An 11-year-old French girl, who spoke no more than three words of Spanish (“Buenos/as días/noches”), slept in Esperanza’s bedroom for two weeks.

That’s why I took this picture of Esperanza setting down full plates of food. She ran around the house in her floral dress, always finding something to do. I realized when I left that she had darned my socks. We had a ritual after every meal: When I would start to wash my dishes, she would scold me and insist, “tranquila, tranquila.” Still, she seemed to dislike housework, promising me on multiple occasions that she would be reincarnated as a man so she could free her mind of it all.

On a weekend away from Esperanza and Vega, I also realized how much I liked cows this summer. Since they don’t perceive cameras as threatening, photographing them felt personal, not distanced. I took this photo on one of those clear, glorious summer days when the warmth makes the world feel very awake. The calf just stood there, and it felt like a reciprocal exercise in looking. She considered me, unfrightened and uninterested. I looked back, and we just stood there together on the top of a mountain, and that was all.

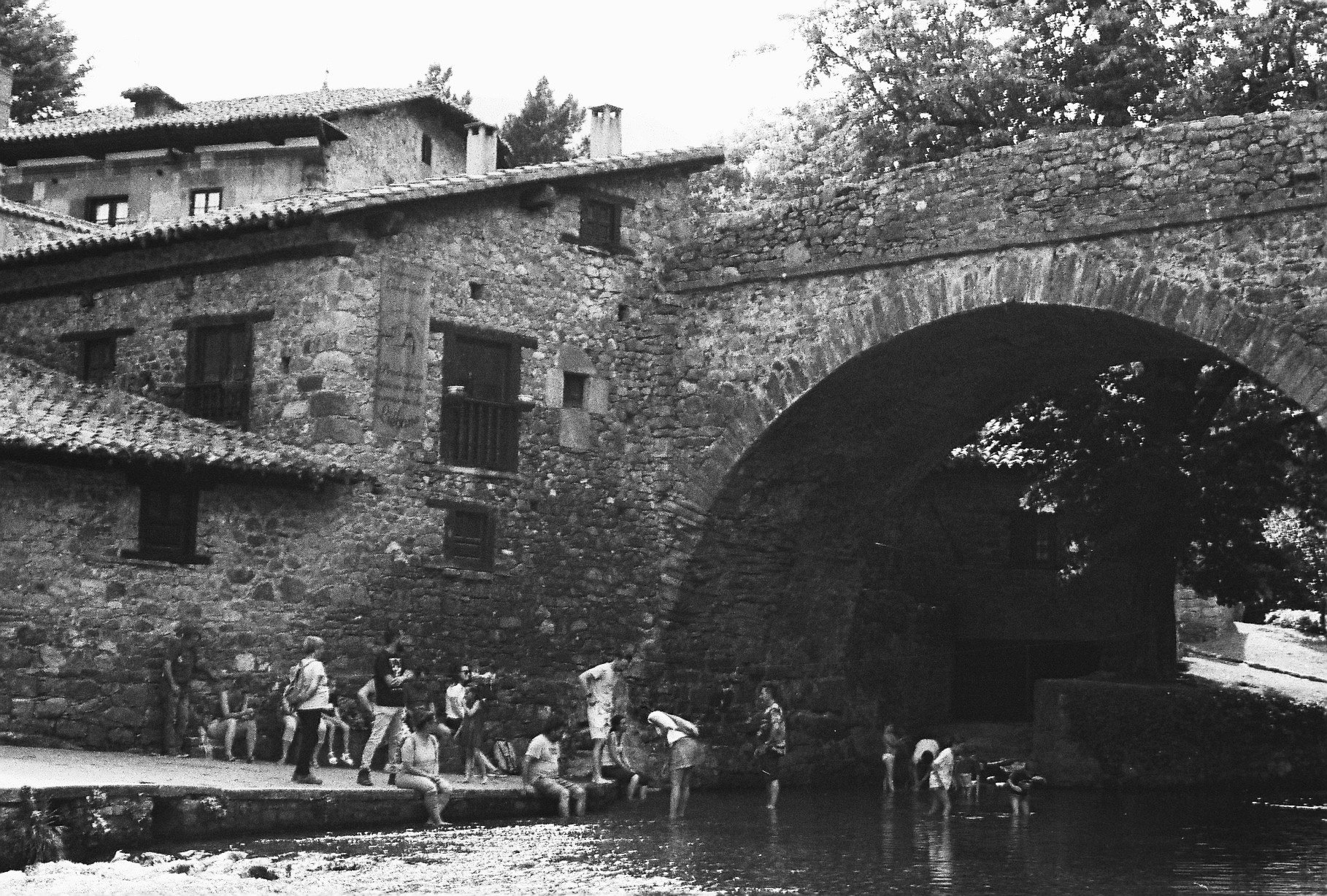

These next two photos capture moments of quotidian communality. I went to the market and the river when I was looking for the anonymity of crowded places.

I imagine that the woman in the first picture is pointing at the ovular frame. “I must have this for my dining room!” she says, with conviction. I hope that painting of the dancing, grinning girl now has a home.

Of course, these photos do little in the way of defining a country. In “The Myth of Sisyphus,” Albert Camus writes, “This world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge and the rest is construction.” When we travel, we tend to construct. We look for a definition of the world because a sense of knowledge distracts from what we will never experience.

But it’s impossible to enumerate all the aspects of people and culture and create one “true” cohesive image. So I will contend myself to this simple act of touching, looking. Of Spain, I will remember the woman bathing in the evening light with feet dug into sand, the calf nursing from its mother on a slowly sloping mountain and Stefano’s candor. I think of perfect ceramic concentric circles, toes timidly dipped into river water and the flower market on a rainy day. I see the wide almond eyes of baby Vega, as she sings to me, “Mira, Carlota.”

Charlotte Hampton is the editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth. She hails from New York, N.Y., and is studying government and philosophy at the College.

She can be reached at editor@thedartmouth.com or on Signal at 9176831832.