This article is featured in the 2023 Commencement & Reunions special issue.

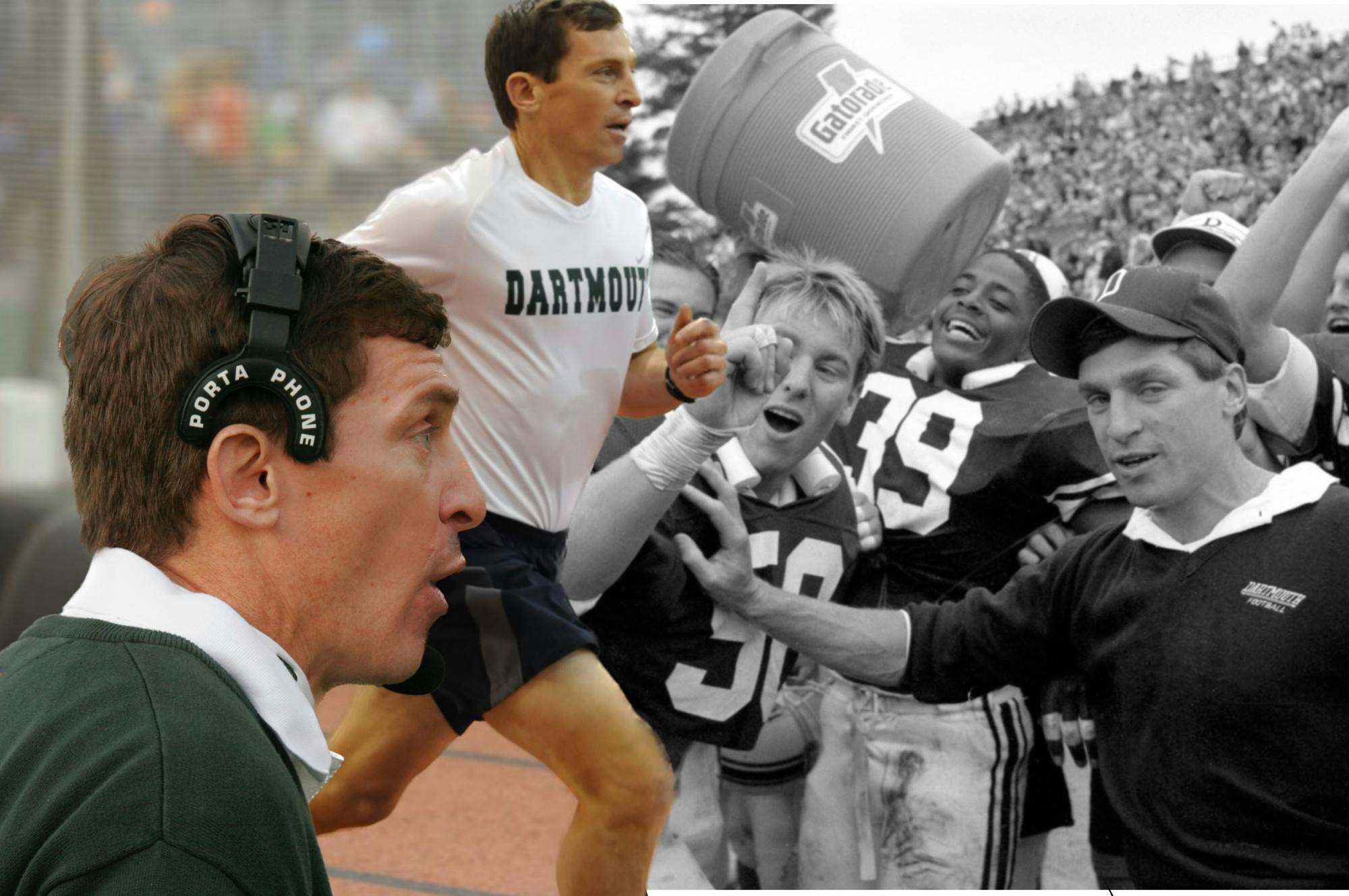

The name Buddy Teevens ’79 strikes a chord beyond Dartmouth — even NFL commissioner Roger Goodell stops when he hears the name.

“Buddy is a force — a force for the good of football but more broadly [for] communities,” Goodell said. “He made football better, but he did it in the context of making Dartmouth better — and at every place he was, he made it better.”

Goodell spoke while standing in a place familiar to Teevens. A complex that Teevens, with the help of his vast array of supporters, rebuilt almost 20 years ago.

Floren Varsity House, a 44,000 square-feet building, was built because of Teevens; Memorial Stadium was renovated because of Teevens.

It was only right, then, that Goodell — a footstep away from exiting Memorial Stadium last Tuesday — stopped when I, an over-eager, freshman reporter, called his name. He stopped because of Teevens.

A chance encounter in France

In the spring of 1977, in a city far removed from rural New Hampshire, Teevens himself was stopped.

It happened in Bourges, France, on a lonely soccer field.

Midway through a pickup soccer game, a flock of muscular French rugby players rapidly approached Teevens.

“They saw Buddy, [whom they immediately called Tarzan], and they immediately recruited Buddy for their rugby team,” Ben Riley ’79, who met Teevens his sophomore spring during a study abroad program, said.

While Teevens was a great athlete, what Riley and Peggy Tanner ’79 remember Teevens more for is his character.

“There’s no one who’s a better human being, person, classmate or friend than Buddy Teevens,” Tanner said.

Teevens has stayed that way, both said, through a coaching career that has taken him to eight different schools. His ties to Dartmouth, though, remain deep.

Recently, Tanner and Teevens were working together on a class gift. Despite managing a Division I football program, Tanner said Teevens dedicated himself fully to the effort.

“He was engaged in every conversation whenever he was needed,” Tanner said. “He made himself available. I feel like his own needs never were a priority. It’s always about other people.”

A helping hand in the sports industry

Teevens’s influence has touched the lives of others in the sports industry, like Callie Brownson. At 28 years old, Brownson, now the assistant wide receivers coach for the Cleveland Browns, had undoubtedly expanded football’s female frontiers.

Having interned with the New York Jets, Brownson, serving as Dartmouth’s offensive quality control coach, was the first full-time Division I female football coach at the time. On September 15, 2018, though, gearing up for her first collegiate game, Brownson found herself on the periphery.

Before its season opener against Georgetown, the Big Green football team sat inside the locker room at Memorial Field awaiting a signature Coach T speech.

“I’m standing outside the door in the locker room because it’s the locker room — now nobody’s changing or anything, everybody’s dressed — but I’m like, ‘I can’t be in the locker room,’” Brownson said, giving a long pause. “I can’t be a part of this moment where he’s gonna get in front of the team, first game of the season, and get everybody fired up.”

But Teevens would not allow Brownson to miss out on the moment.

“[Teevens] walks in … and he stops, and he looks back at me, and he’s like, ‘What are you doing out here?’” Brownson explained. “‘Well Coach, it’s, it’s — it’s the locker room.’ And he goes, ‘I don't care. You're part of his team. Get in here, immediately.’”

That, Brownson said, is the moment she knew Teevens was special.

“To me, it’s just always funny because I overthought,” Brownson explained. “All [Teevens] wanted to do was make sure that everybody who was part of the program felt like part of the team, because we all were.”

Teevens bred new life into her career once the Jets internship was over.

“I didn’t really think I was ever going to get back into football at a high level again — as a female in the sport, it was just hard,” Brownson said. “I don’t think giving up is the right [phrase], but I just … put football as a ‘this isn’t gonna happen’ kind of deal for me.”

Hiring female coaches — Brownson, Chenell Tillman-Brooks, Jennifer King and Mickey Grace — and eliminating tackling in practice, as mentioned in the New York Times and the Washington Post, is just part of who he is, Brownson said.

A risk taker

In 2010, as the national conversation surrounding chronic traumatic encephalopathy among football players heightened, Teevens decided Dartmouth football players would no longer tackle during practice — a decision that fellow coaches said would surely get Teevens fired, according to Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

Nevertheless, the Big Green’s 2010 season was its best since 1997 and missed tackles dropped by half, according to the Magazine.

“To him, he was just tasked with this bigger purpose to do the right thing, to change the game in the right way,” Brownson said. “Whether it was popular or not … it didn't matter to him.”

Goodell, too, said that he appreciates Teevens’s efforts as the NFL continues to face backlash for the risk inherent in such a physical game.

“He was a pioneer,” Goodell said. “He had the courage to do it. And he did it for all the right reasons, which is making the game safer for our players.”

In the spring of 2011, Teevens sought out former classmate and Thayer School engineer John Currier ’79, Th ’81 with a question: Could Currier make a tackling dummy mobile?

The answer was yes, and soon Teevens was the chairman of MVP LLC, a company that designs mobile tackling dummies. Current CEO Quinn Connell ’13, who worked on Currier’s project as an undergraduate assistant, says the project would not have been possible without Teevens’s love for the sport, the Dartmouth football program and the College.

“He has an enthusiasm and energy that just sort of draws people to him,” Connell said. “And he’s created this network of people that are fans of Buddy and believe in the culture and ethos that Buddy lives by.”

Doing things his own way

While it’s hard to forget your first ever Orange Bowl, it’s harder, Dartmouth interim football head coach Sammy McCorkle said, to forget the first time he met Teevens.

When Teevens first started his coaching stint with the University of Florida right before the 1999 Orange Bowl, adapting to the Gator atmosphere was a challenge for Teevens. McCorkle, a Florida native, Gator walk-on and graduate assistant at the time, recalls the culture of the Florida football program as being “really laid back.”

Teevens, who had grown up in Massachusetts and attended Deerfield and Dartmouth, approached the job differently.

“Everybody kind of comes in pulling paper out of their pockets, or a pen, or whatever,” McCorkle said. “And here comes Buddy as an organizer, and he opens [a binder] up and he has all these different colored highlighters.”

“I’m watching him, like, ‘Who’s this guy?’” McCorkle explained. “And I remember our ops guy was like, ‘Yeah, that’s an Ivy guy for you.’ But I just knew right there, this guy’s different — in a good way.”

McCorkle put his full faith in the Northerner when Teevens, returning to Dartmouth in 2005, invited the lifelong Floridian to Hanover to repair the Big Green’s struggling program.

“I said, ‘heck yeah,’” McCorkle said. “Starting essentially at the ground floor with him and watching him, and how he went about building this thing back up — I couldn’t ask for a better opportunity ever.”

McCorkle, who began coaching without Teevens for the first time in 18 years in March, said he recognizes that the program he is stepping into — the one Roger Goodell visited last month — is Teevens’s program.

“The one thing I really appreciate … was his persistence of wanting to accomplish something that … was going to be important to this football program,” McCorkle said. “Starting from getting these facilities built and getting the alumni back involved in this program.”

McCorkle paused, as if he was soaking in memories from the last two decades.

“Sometimes as a coach you’re brought up as, ‘Hey, this is the way we do it,”’ McCorkle explained. “And sometimes some of his ideas you’re like, ‘Where’s he going with this?’ But I’ve learned, knowing him long enough, that it wasn’t just crazy. He had a plan — he knew what he was trying to accomplish — just his way might have been different from a lot of people’s.”

A wide web of support

Although Brownson’s career has taken off, Teevens continued to check in with Brownson every week, sending her messages after every win and loss, first when she went to the Bills and then the Browns.

“I was really only [at Dartmouth] for a year, and he could easily say, ‘Hey, congratulations, et cetera,’ and move on. But that’s not that's not who he is. He’s a person where relationships matter the most.”

It all ties back to Teevens’s first experience at Dartmouth, McCorkle said.

“When he came up here on his visit, the coaches didn’t even know his name,” McCorkle said. “He felt like he was kind of the outcast a little bit — and he doesn’t want people to feel that way.”

Teevens’s culture of inclusivity, McCorkle said, is something he will continue to make a priority.

“Regardless of who you are, what your status is, if you’re willing to commit to something and do the work, or show that you’re invested in something, your value’s just as high as anybody else,” McCorkle said.

And while Teevens recovers, people have invested in him.

“You always knew there was a large group of alumni that were really excited about Buddy and what he’s done here,” McCorkle explained. “But … I still today get emails, almost on a daily basis, from individuals — some of whom I’ve never met before or spoken to — and they just reach out and offer their support.”

Goodell said “Kirsten and Buddy are like family members” to him.

“[Teevens] has got something special,” he said. “It’s like a beacon. He just lights everybody up. And he just motivates people. And there’s not a single person who he doesn’t try to help.”