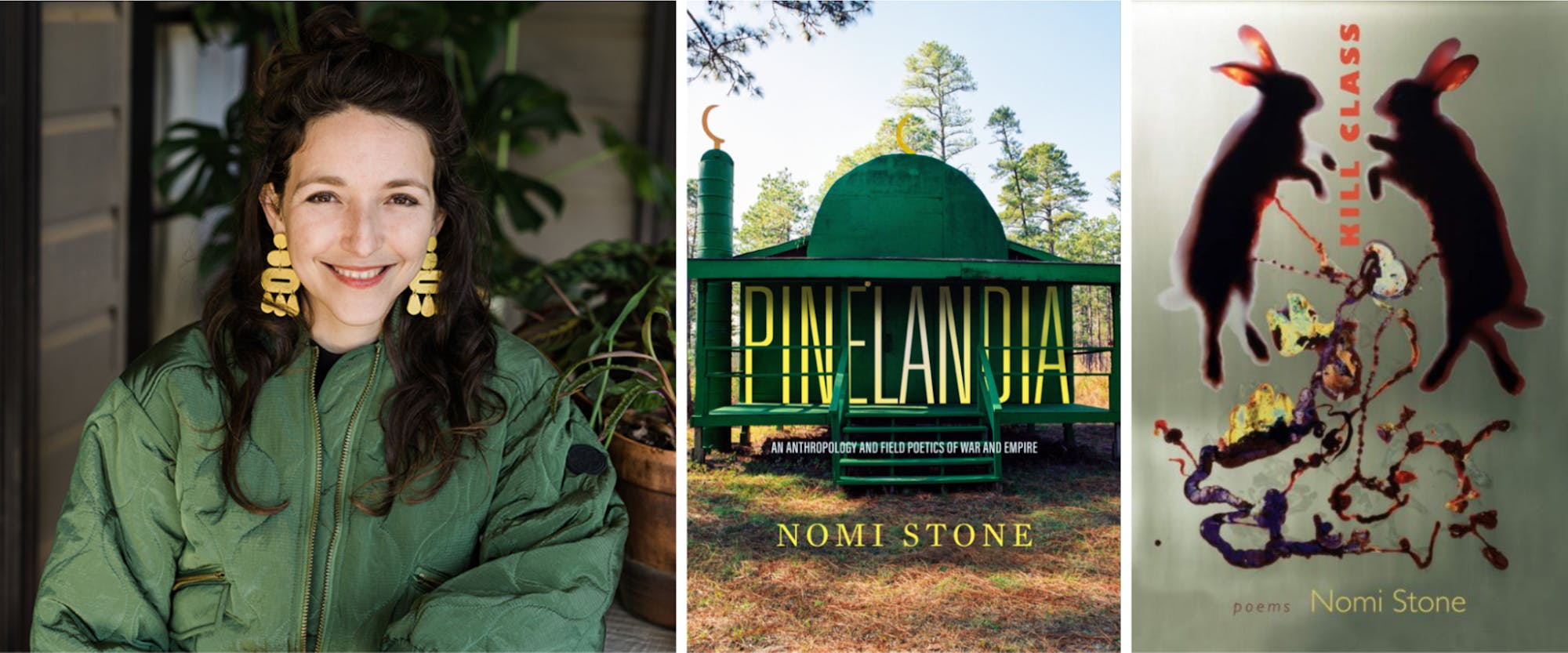

On May 10, poet-anthropologist Nomi Stone ’03 read excerpts from several of her poetry collections and participated in a Q&A session at Still North Books & Bar. Stone is an award-winning author of the poetry collections “Kill Class” and “Stranger’s Notebook,” whose poems have appeared in “The Atlantic,” “The American Poetry Review” and “The Best American Poetry.”

After completing a B.A. in French literature at Dartmouth, Stone received a Fulbright scholarship to pursue creative writing in Tunisia and went on to earn a Ph.D. in anthropology at Columbia University, an M.F.A in poetry from Warren Wilson College and an MPhil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at Oxford University. She has conducted postdoctoral research in anthropology at Princeton University, and she now teaches poetry as a creative writing professor at the University of Texas at Dallas.

A finalist for the Atelier Award, her latest book and first academic monograph “Pinelandia: An Anthropology and Field Poetics of War and Empire” explores US military pre-deployment training exercises involving mock-creations of Middle Eastern villages. The book delves into the complex microcosms of the Iraqi role-players employed within these faux villages across the forests and deserts of America, as well as the ethical questions which arise from utilizing such methods for military advancement. During the talk, Stone described the effects of the mock village activities on both the actors and soldiers; these activities include digging fake graves, fake grieving and even learning how to fake empathy through body language and facial expressions.

“These spaces can be incredibly reductive and result in a harrowing cementing of ideas for these young soldiers: for example, they start to associate the call to prayer with bombs, [and] pregnant women with danger,” Stone said.

During the latter half of the reading, Stone shifted into more personal subject matter, specifically queer family-making. Through vivid, lyrical verses, she shared how becoming a mother has prompted her to turn her critical reflection upon herself and how she fits into our society.

“For me, poems are the holiest houses for the self, though what capacious houses they might be,” she said. “In the broader sense of the term, fieldwork for me is about becoming and asking questions of the self, engaging with the crackle of the world.”

When asked during the Q&A session how she decides which moments to represent in poetry and which to discuss through more traditional ethnographic writing in “Pinelandia,” Stone elaborated on her field notes.

“I have really zany field notes,” Stone said. “I put everything into my field notes because I wanted them to produce multiple kinds of writing. The poems come first; they are immediate. But they need heat: I can’t write a poem unless something really shakes me. I always need a sensory tether for a poem that is linked to my own affect.”

After Stone’s reading and the Q&A, Stone sat down with The Dartmouth to reflect on the challenge of avoiding the aestheticization of violence — particularly in an artistic literary form that captures others’ experiences of extreme physical and psychological trauma.

“Poetry itself beds up against silence. A poem, because of its very form — which is line break, which is white space — is a form that invites the unsayable, the hardly sayable: the threshold points,” Stone said. “So with questions of violence, where certain things cannot be rendered ethically, the poem is actually the best form in which to do this, because it allows you to hit against the white, the edge: the limit point.”

Stone said her ethnographic project arose when one of her closest friends from Dartmouth began film work in a few of the mock villages. Having just returned from conducting fieldwork in Iraq herself, Stone realized that some of the same people she had been following in Iraq had actually moved to the US and begun role playing in these villages.

At Still North, Stone was introduced by anthropology and South House professor Sienna Craig, who said she is inspired by Stone's interdisciplinary work and praised Stone’s personal and artistic character.

“As an anthropologist who writes poems or an ethnographer who finds solace in reading and writing poetry, discovering Nomi’s work some years ago was like finding a perfect pebble on a rocky shoal,” Craig said. “Here was someone living and writing not in ‘either, or’ reality, but bravely and beautifully bringing forth a ‘both, and’ world: a ‘poet-anthropologist.’ An ‘anthropoetica.’”

Craig alternates teaching ANTH 73, “Main Currents in Anthropology: Theory and Ethnography” with anthropology professor Laura Ogden, and when considering new, innovative ethnographic texts to include in the syllabus, Stone’s “Pinelandia” came up as a perfect fit for the course. Craig said she felt excited to bring Stone to campus — especially upon learning that she is a Dartmouth alum. In an interview with The Dartmouth, Craig shared that she and Stone are currently collaborating on a new collection of flash ethnography.

“I first got to know Nomi working together on a collection of flash ethnography that she and a mutual friend were editing during the pandemic, and to create that collection, we did a series of virtual writing workshops, which really deepened my appreciation for her and her work,” Craig said.

This event was sponsored by the anthropology department and English and creative writing department, as well as by South House. As the South House professor, Craig said she aims to connect different parts of the Dartmouth community, including faculty, graduate students and undergraduates. She added she hopes to reflect Stone’s goal with her writing: to bring together the traditionally separate areas of research and poetry and, more broadly, fieldwork and life.

Alexandria Casteel GR — a graduate student in the Ecology, evolution, environment and society program, who also attended the event — said she applauds Stone’s courage in her experimentation with different writing styles.

“So often within the constraints of a discipline, we’re told our writing has to look a certain way, and for Nomi, it’s sort of taken this shape where poetry and ethnographic writing are read simultaneously, which I think is quite beautiful,” Casteel said.

The reading was followed later in the week by a two-hour workshop led by Stone. The workshop was attended by a mix of anthropology faculty, graduate students and members of Anthropology Professor Laura Ogden’s senior seminar. This workshop involved a long, reflective walk through campus, followed by a writing exercise. Casteel, who attended both the reading and the workshop, said she appreciated the opportunity to learn more about Stone’s writing process and to write with others.