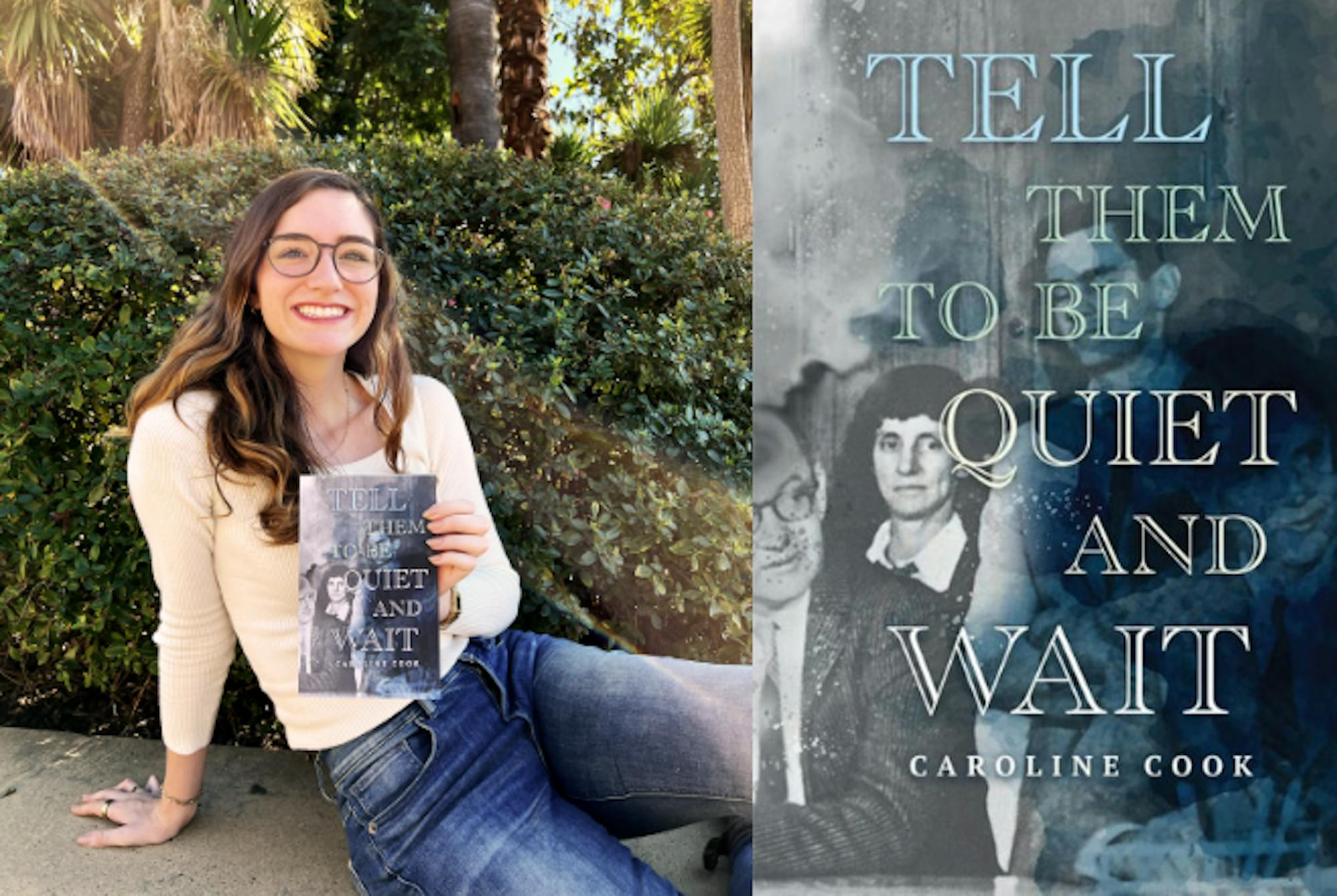

Caroline Cook’s ’21 first novel, “Tell Them To Be Quiet and Wait” will be released on Nov. 1 to coincide with Dartmouth’s 50th anniversary of coeducation. The book is inspired by the life of Hannah Croasdale, Dartmouth’s first female professor to receive tenure. The novel follows two fictional women from two different times, 1935 and 2015, and explores how each navigates academia and science all the while emulating the true events of Croasdale’s life. During her time at Dartmouth, Cook studied Croasdale extensively through a student research fellowship at the Rauner Special Collections Library.

The Dartmouth sat down with Cook to discuss her writing process, the importance of inheriting a history and what the Dartmouth community can learn from reading the novel.

How did you discover Croasdale’s story?

CC: It's an interesting story actually because I was the first person to do the Historical Accountability Research Fellowship, which is out of Rauner Special Collections Library. Initially, the fellowship was about finding something interesting in the archives and learning the process of archival research. Then the folks at Rauner said, “actually we’re pivoting the fellowship.” And then everything had to be about Dartmouth and historical accountability. Jay Satterfield, who was the head of Special Collections suggested I study the first first female professor at Dartmouth, Hannah Croasdale.

What compelled you to write this story?

CC: I was an English major and I have always been a writer. And Jay, who was advising me, said “I think you might want to do something with this story.” I was so interested in the parts of her story that I couldn’t prove but that I had a lot of opinions about. The thing about the archival work is that some of the more interesting parts of the story are the things that you can’t find. We call them the silences in the archives. I did a lot of nonfiction writing, but it really felt like to truly show what I had learned about her life and about this generation of women, it felt like it needed to be fiction.

What creative liberties did you take in retelling Croasdale’s story, and were those challenging decisions to make?

CC: I took a lot of liberties and I think I’m very haunted by the fact that I will never know if I told this story in a way that she approves of. I’m very specific about the way that I describe the story because I don’t pretend to know how she felt.

But that said, I wanted to explore all of the ways in which not having language for a lot of the things that we have language for now might have changed how somebody described their experience at the time. So do I believe that the only woman in a department might have faced some sexual harassment? Yeah, I believe that — but there was no way to describe those things until the 70s when sexual harassment and sexual assault got their own vocabulary. That was really difficult. I created some scenarios that I can’t prove happened, but I think it’s more about her reaction to those scenarios that I believe is accurate, having studied this historical moment.

This story features parallel storylines between Dr. Beverly Connor in 1935 and Lena Rivera in 2015. Why did you employ this device and what is the impact of such a structure?

CC: One, I wanted to show the two women in the same place and highlight the fact that people occupy the same spaces without thinking about the people who occupied them before. It’s something we all do, and it’s such a powerful tool — especially when those storylines never intersect. When you’re reading the book, you keep waiting for there to be some obvious connection between them to meet or interact in some way. And that doesn’t happen, because that’s not how the world works — but that doesn’t mean that those stories are not related. That’s a part of the point that I’m trying to make in the book: your story is connected to all of the women who came before you at Dartmouth, whether you think about it or not.

Could you elaborate on the significance of the release date?

CC: The novel is launching on November 1, partially to tie in with the 50th anniversary of coeducation. We’re at this particular moment where we could just be looking forward and celebrating all of the progress that we’ve made, but we cannot properly appreciate how big of a deal that progress is if we don’t also create space for looking backwards and knowing who’s responsible for getting us to this moment.

Why is it important for our community to highlight and pay tribute to figures in Dartmouth history like Croasdale?

CC: Who gets to tell stories at Dartmouth or any institution is always going to be challenging. As an institution that focuses on education and therefore is focusing on the future, I think our understanding of the future is only ever going to be as strong as our understanding of the past. I think that capturing as many perspectives of the important figures in our history will set us up better for the future. That’s why this fellowship in the library is so important: There are untold stories that we need to dig out and pay attention to and learn from.

What perspective can readers gain from reading this story?

CC: That it’s not just about this one story, this one person. It’s not just about Dartmouth. It’s not just about women. It’s not just about science. It’s about understanding what it means to inherit a history.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Caroline Cook ’21 is a former Opinion editor for The Dartmouth.