On April 27, a repatriation ceremony will take place at the Mohegan Cultural and Preservation Center in Connecticut for the College to return the Samson Occom papers, which include diaries and autobiographical statements belonging to Occom — a co-founder of Dartmouth — to his native Mohegan Tribe.

Part of the significance of the documents lies in their linguistic information and history. According to College archivist Peter Carini, among the 117 documents and two books in the collection, there is a primer that contains what is believed to be the oldest example of the Mohegan Tribe’s written language.

According to Mohegan Tribal Council vice chairwoman Sarah Harris ’00, the last fluent speaker of the Mohegan language passed away in 1908, at a time when many Mohegans had stopped teaching the language out of fear of “retribution” from local teachers. Harris wrote in an emailed statement that the Mohegan Language Project plans to use the primer substantively as a teaching tool towards the Mohegan language revitalization efforts.

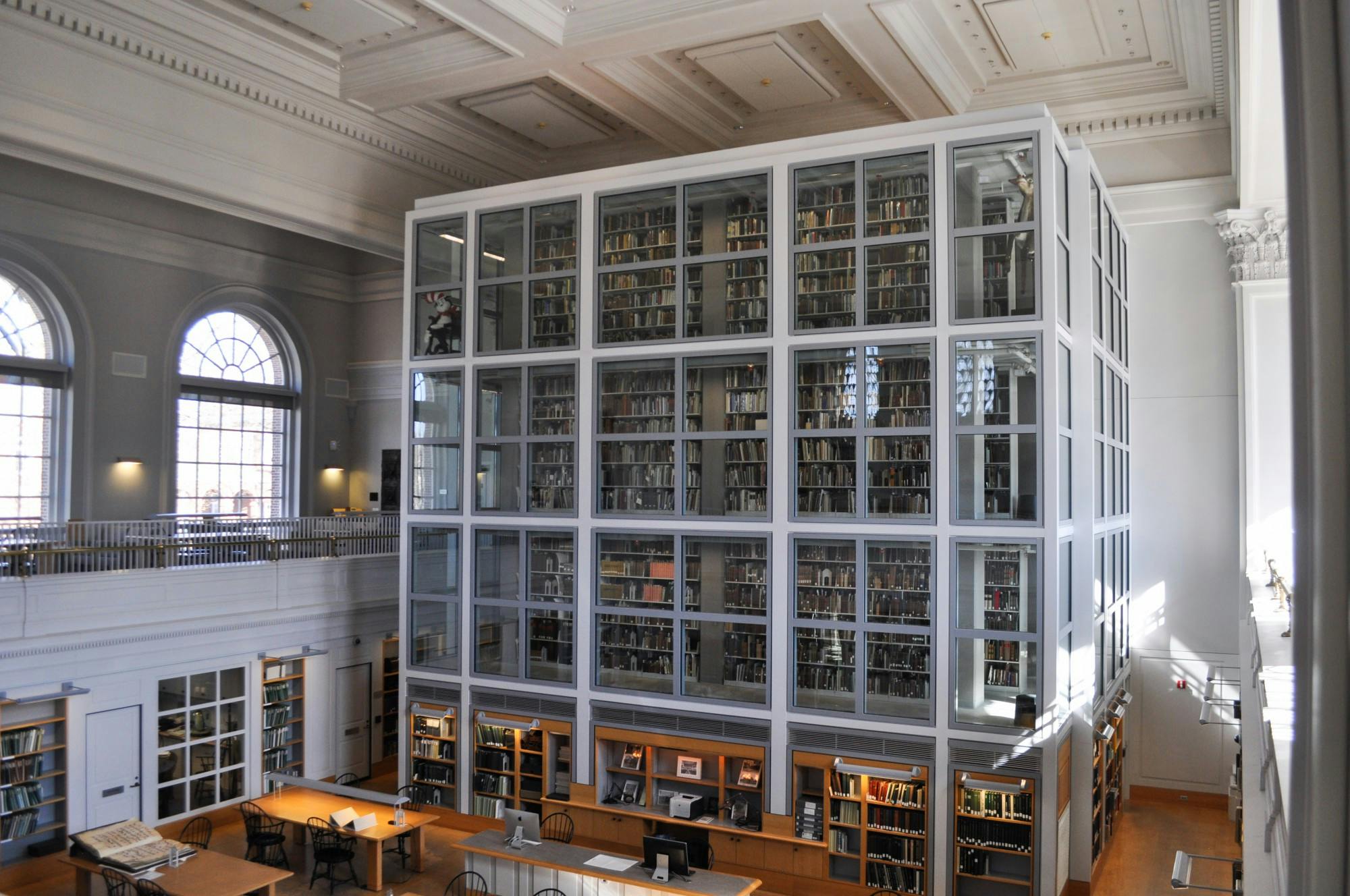

The Occom papers are currently housed in an underground storage facility between the back of Rauner Library and the east wing of Baker Library. According to Harris, the return of the Occom papers is particularly meaningful for the Mohegan Tribe because the Mogehan people believe that objects and writing hold their maker’s spirit within them.

“With the return of his papers, Occom is coming back to our homelands and our people,” Harris wrote.

Taught by Eleazar Wheelock, Occom was considered a remarkable student by any standard, according to Native American studies professor Colin Calloway. Calloway said it was this experience that prompted Wheelock to found Dartmouth College with the initial intention of educating Native American youth.

According to Carini, by assisting the Mohegan Tribe with legal documents and fighting for their land rights, Occom hoped to use his education to support his homeland.

However, according to Calloway, in Dec. 1765, Occom traveled to England to raise money for what he believed would become a school for Native Americans which instead became Dartmouth College — “another school basically for white students,” Calloway said. Before returning in 1767, Occom had raised roughly 2 million pounds in today’s money, Carini said.

Then, in 1777, Occom wrote a “scathing” letter to Wheelock regarding Wheelock’s broken promise to care for Occom’s family while Occom was away and repurposing of the collected funds to create a college that served sons of New Englanders, Carini said. According to Calloway, in the letter, Occom said that Dartmouth should not be considered an alma mater, but instead an “alba mater” — a white mother.

Carini said that Occom never saw Wheelock ever again and never set foot on Dartmouth College.

“I’m encouraged by [the repatriation] because it is a step in the right direction,” Calloway said. “It is an important first step towards restoring a relationship that was severely damaged a very long time ago.”

Carini said that staff from the College’s libraries and the Hood Museum of Art attended workshops with the Mohegan Tribal Librarian and Tantaquidgeon Museum to better understand how to collaborate with Indigenous communities, as well as Occom’s role in the founding of Dartmouth. According to Carini, members from administrative offices such as the admissions office were also invited to these workshops.

“We think [they] could benefit from better understanding of the story and the background and how to work with indigenous people a little bit more,” he said.

According to Carini, the College is also “in conversation” with members of the Abenaki Tribe — the land of whom the College was built on — in Odanak, Quebec concerning tribal materials still held by the College. The process for any items to be repatriated has yet to be determined. One factor in determining what items should be repatriated is the question of how the item was originally sourced and if it was bought or stolen, Carini said.

According to Carini, “a lot” of materials held by the Hood museum were originally sold by members of the Abenaki.

“The Mohegan [repatriation] came up very quickly and we reacted to it but we want to prepare ourselves before we field any additional requests because there need to be some internal protocols in place for us to judge when it is most appropriate to return items,” Carini said.

In regards to repatriating the Occom papers to the Mohegan Tribe, Carini said that he is “really excited.”

“It’s very rare in my job that we get to have an opportunity to return [such documents] in such a direct way and in a way that starts taking some steps toward correcting harms from the past and creating reconciliation,” he said.

Harris shared Carini’s optimism.

“This repatriation marks the beginning of a new chapter in the shared history of the Mohegan People and the Dartmouth community, one in which Occom’s dream of an education for Native students moves closer to fulfillment,” she wrote.

Arizbeth Rojas ’25 is a managing editor of the 181st directorate from Dallas, TX. When she’s not listening to DJ Sabrina the Teenage DJ or planning her next half marathon, you can find her munching on a lox bagel.