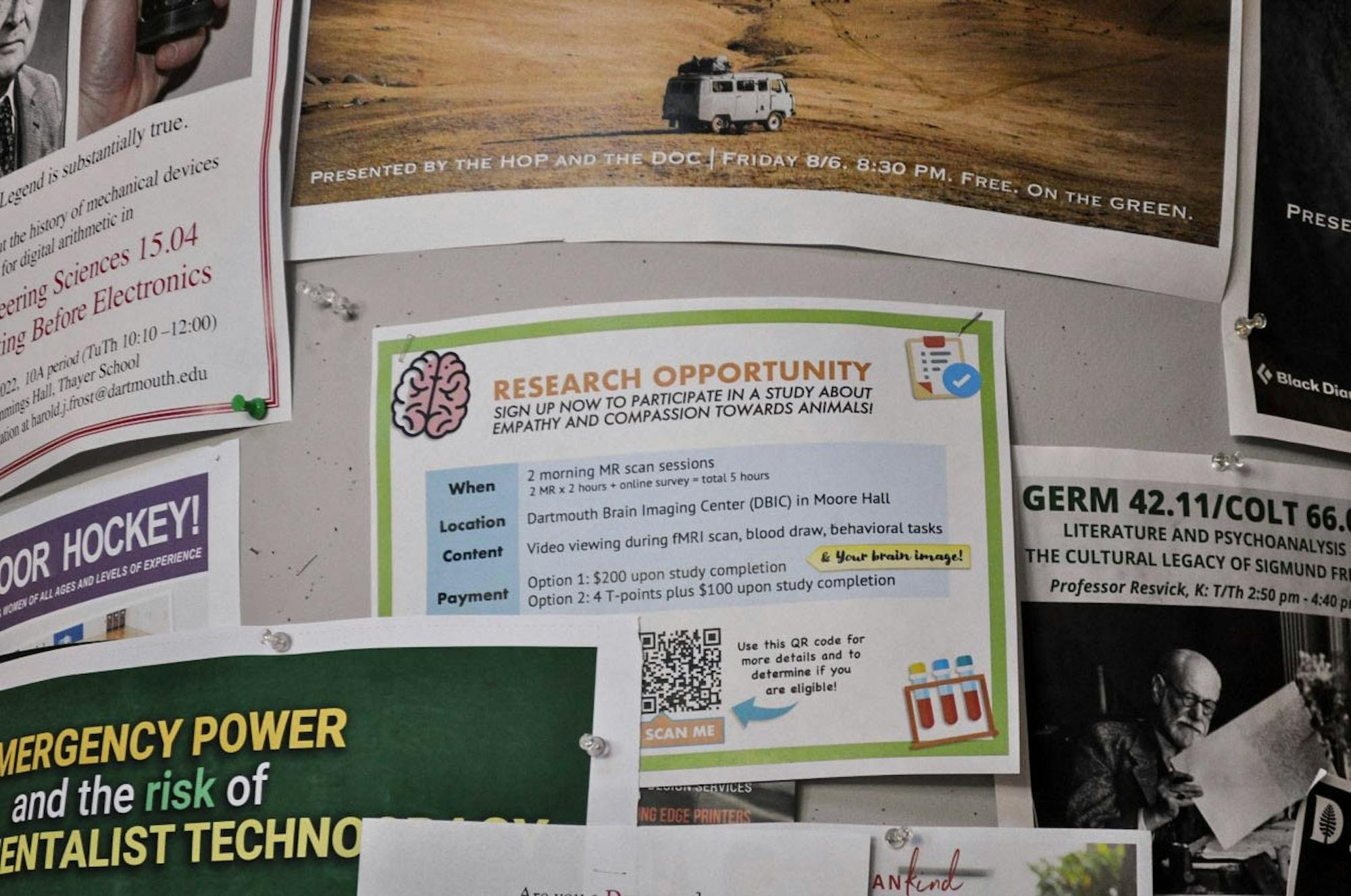

On my way out of Sanborn last week, I found a poster taped to the door. In big orange letters, it advertised a “Research Opportunity,” surrounded by cartoon images of test tubes and brains. I stopped to read, intrigued: “sign up now to participate in a study about empathy and compassion towards animals!” The logistical information was laid out clearly: Where? Moore Hall. When? Two morning MRI scan sessions. Compensation? Up to $200 and — highlighted in bright yellow — an image of your own brain.

The sign-up form was conveniently linked to a QR code at the bottom of the poster. I scrolled through the form, which provided more background information on the study. I clicked through the first pages of the sign-up form, scanning sections about data collection, payment, screening, privacy and consent. After this in-depth information, though, signing up seemed pretty easy: simply pressing the “I agree” button on the screen. Although I ultimately decided against volunteering myself as a participant, a few days later, I had the opportunity to discuss the study with its primary investigator, neuroscience professor and director of the Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Laboratory Dr. Tor Wager.

“We’ve been studying emotions and affect, which is basically how you create feelings,” Wager said.

In this particular study, he describes, “people watch movies where there are legal, currently-practiced animal production processes … [where] animals are really suffering.”

Using MRI scans, Dr. Wager and his team evaluate how watching these videos affects participants’ brains and immune systems. To do this, they need volunteers.

“We’re recruiting broadly from the community, not just students,” Dr. Wager said. “We’ve been putting up flyers and advertising … [and] people are quite interested in signing up.”

In Dr. Wager’s study, participants donate blood samples and undergo two MRI scans, which they are allowed to keep afterwards. According to Dr. Wager, brain imaging studies are common in the psychology and brain sciences department thanks to the MRI scanner located in Moore Hall.

Another experimental study currently underway at Dartmouth is looking into improving oral alternatives to the polio vaccine. Sirey Zhang ’20, a current student at Geisel involved in the study, explained that while most people in the U.S. receive the injected polio vaccine, there are oral alternatives that actually confer a greater amount of immunity. The catch, though, is that they are less protective against virus mutations. Zhang’s team, along with teams at schools like the University of Vermont and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is working on developing a new oral vaccine that prevents these breakthrough cases.

While polio has been eradicated in the U.S., it still exists in many countries around the world.

“There’s something huge to say about humanity coming together, working hard to eradicate this disease that has harmed so many people,” Zhang said.

Much of this effort comes from study participants, many of whom are Dartmouth students. In order to recruit volunteers, Zhang’s team posted advertisements to Facebook and hung up posters in locations such as Dick’s House and the Hop. They also employed Listserv, sending out an email that I remembered receiving at the beginning of the term. Zhang’s team has recruited over twenty patients so far.

In terms of demographics, the participants are split “half and half” between Dartmouth undergraduates and community members from around the Upper Valley. Each patient receives a dosage of the oral vaccine, after which stool samples are collected weekly or biweekly for at least fifty-seven days, along with other monitoring processes. Participants receive $1,100 or $1,200 — depending on the group they are placed into — as compensation.

Studies such as Zhang’s are closely linked with both Dartmouth-Hitchcock Hospital and the College.

“Dartmouth-Hitchcock is a teaching hospital,” Zhang said. “It’s close to the college, it does a lot of research activities, [and] there are lots of trials and studies that involve … recruiting students.”

These students may participate out of interest in the study, to make money on the side, or to earn “T-points” for psych or neuro classes. As Yangyang Li ’22 explained, these T-points, accumulated by participating in studies, can raise the student’s grade by a certain amount. Li herself has participated in various studies since freshman fall. One study involved receiving burns and gauging her pain response, while another, which she is technically still contributing to, uses an app to collect data about her daily habits.

“I’m pretty sure it tracks a lot of information,” Li remarked. “Like how much I’m walking, where I’m going, my location … stuff like that.”

“But as far as what the study is doing,” Li added. “I actually have no idea.”

She doesn’t even know if the researchers will eventually reveal the purpose of the study to her — although she hopes they do, out of personal interest. Li described that her participation in the study was driven primarily by the incentive of receiving class credit.

“I’m not really like ‘oh wow, I’m so proud of myself.’ At the time it was just something that I did to improve my grade … [and] make some extra money on the side.”

However, Li added that as an economics and math major, she “really [understands] the importance of data.” Her contribution to the study is not lost on her: “because it takes ten seconds out of my day, I’m like ‘why not help?’”

Dr. Wager echoed the importance of student participation in research, even if driven by compensation or T-point accumulation.

“I think participation in research is a partnership,” he said. “[Volunteering for studies] has a tremendous value for science, for our research community and for making Dartmouth the great intellectual institution that it is. And students are a huge part of that.”

These partnerships — between student and researcher, study participant and scientific knowledge — drive the collective advancement of knowledge at Dartmouth. At a school where researchers and students coexist and interact on a daily basis, both groups are able to actively contribute to a growing body of knowledge and a strengthened academic community. These studies, from Sirey Zhang’s polio vaccine to Dr. Wager’s animal empathy inquiry, provide almost any Dartmouth student with the opportunity to participate in groundbreaking research — and maybe earn a little cash on the side.