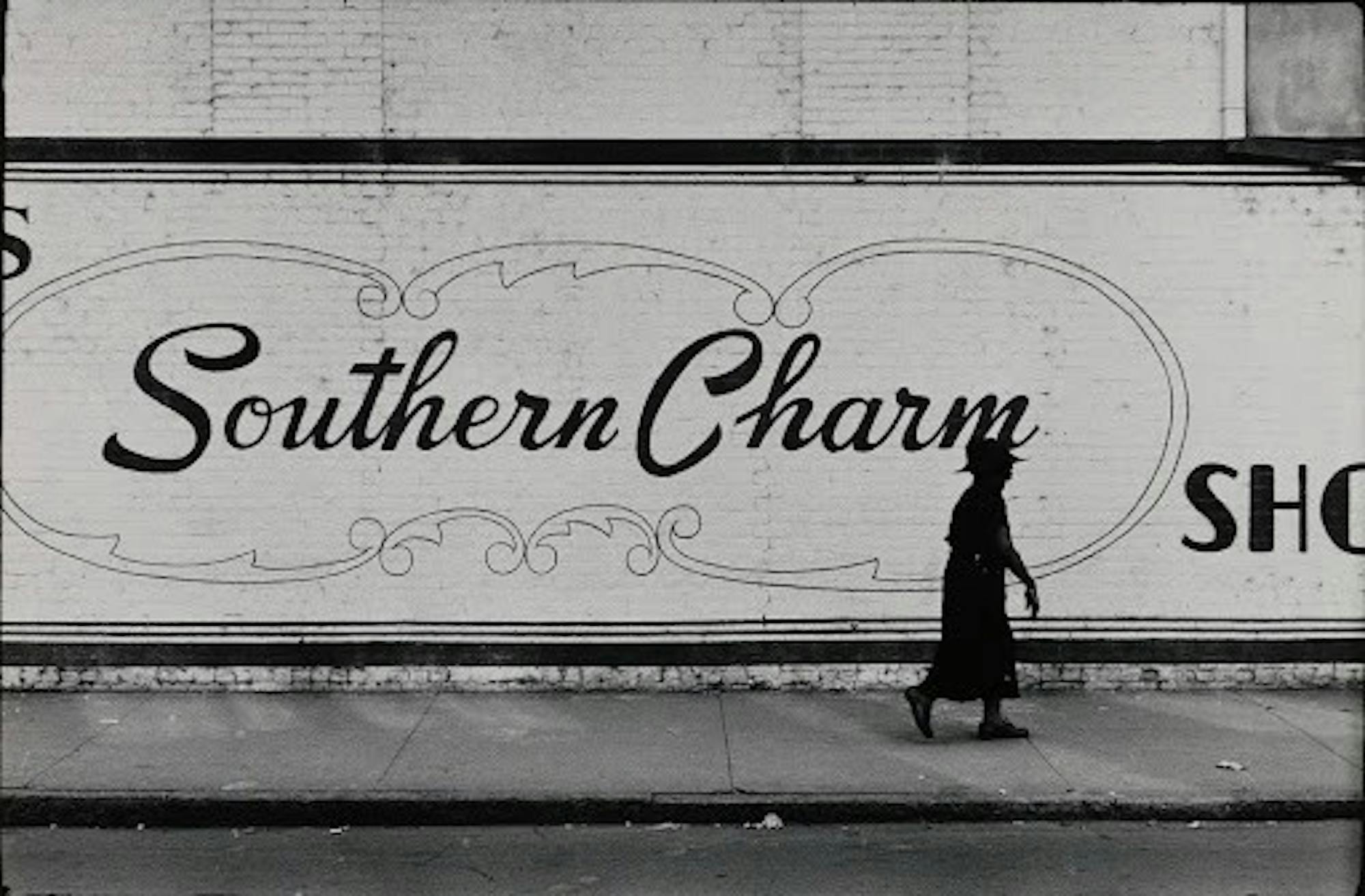

On Jan. 14, the Hood Museum of Art hosted Conroy intern Abigail Smith ’23 for the latest installment of the museum’s “A Space for Dialogue” series. During the Hood’s first in-person gallery talk since winter 2020, Smith discussed her curated collection, “Southern Gothic,” which examines the complex and often macabre world of the Southeastern U.S. Featuring pieces from the Jim Crow era to the 2010s, Smith’s collection aims to capture both the darkness and light of the Southern Gothic era, according to the event’s promotional materials.

Smith, an art history major from Macon, Georgia, was inspired by her Southern roots to create the exhibit and tell the story of the Southeast.

“In doing Southern Gothic, my goal was to uplift the minority groups and call attention to a lot of the social issues that I think have gone on for too long in the Southeast,” said Smith.

Smith said she is trying to tackle the ways in which public perceptions of the South can inhibit positive change in the region through her curating.

“Southern Gothic” is a literary genre popularized by Southern writers that features themes of the supernatural while showcasing the South’s complicated and dark history, often as it relates to racism and other social issues of the region. To transform this into visual art, Smith researched the Hood’s collection to find pieces that related to the South, the Civil Rights era, Reconstruction and the Great Depression while looking for a dramatic, black and white palette.

During the gallery talk Smith gave a presentation in which she discussed her curation process and the motivation behind “Southern Gothic.” Smith went into detail about the vibrant wall color, “Haint Blue,” seen on porch ceilings and front doors in the South, which was once used to ward off malevolent spirits by the Gullah Geechee people, who are descendants of enslaved Africans.

Emily Hester ’23 said she came to the gallery talk with a basic understanding of Southern history but left with a whole new perspective.

“I didn’t really know what Southern Gothic was at all, but I knew a lot about what we’ve learned about the history of the South in school,” said Hester. “I think analyzing [Southern history] through an artistic lens and the style of Southern art gave me a more complex conception of a lot of the pieces [Smith] was talking about.”

Lisa Sumi ’23 said she left the gallery talk with more knowledge of the relevance of the Southern Gothic genre.

“I really enjoyed how most of the pieces were in black and white, but I liked the way [Smith] added two color pictures at the end,” Sumi said.

Hood curator of academic programming Amelia Kahl ’01 said the care and craft Smith put into her show have come together to create a wonderful exhibit.

“[Smith] always has a great story to tell,” said Kaul. “She is really connected to her family, and, in the show, thinks through her identity as a Southerner.”

Interns at the Hood have never worked with the niche Southern Gothic genre before — Kahl described Smith’s idea of relating visual art to the literary genre as “brilliant.” However, the task was not without challenge, as certain photos Smith wanted to display could not be displayed.

“If anything that I wanted in my show had been out on view within the past few years, it couldn’t come out because, if [the photographs] are out in the gallery, they are being damaged,” said Smith. “So, you have to be very sparing about how frequently you display certain pieces.”

Smith believes that the photo “Press Conference with Lee P. Brown, Atlanta Chief of Police, at Task Force Headquarters” by Leonard Freed best represents her goal to shed light by exploring the darkness of South’s history. The picture is from the Atlanta Child Murders of 1979-1981, when 25 Black children went missing and were found brutally murdered. At the time, the leader of the investigation was only able to make an arrest for two of the murders.

Recently, authorities reopened the investigation and collected DNA from the dozens of other children that were killed.

Smith said that public awareness on the murders has increased as a result of more media on the topic, such as the HBO series “Atlanta's Missing and Murdered,” adding to the public pressure to reopen the case.

“Right now, things are hopefully getting better, and the reason for that is because we are putting more national attention on them,” said Smith. “If we just paid more attention to the problems in the South, we could help the people that need that attention a lot.”

Smith said the piece that is most “Southern Gothic” and the focal point of the pamphlet is “Breakfast Room, Belle Grove Plantation” by Walker Evans, a photographer who was supported by the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program. The photo depicts an ornate breakfast room in the abandoned Belle Grove plantation in Louisiana.

“This was probably once a beautiful home,” said Smith. “But during its most opulent eras, its walls were filled with ugliness. When this building was at its height of luxury, many were suffering.”

The Belle Grove plantation reached its peak during the antebellum era while its residents exploited enslaved people’s labor for their own livelihood, Smith said.

Smith noted that her hope for the show is to draw attention to the South, aiming to help change negative perceptions of the region that prohibit productive change.

“I think artists have a profound capability to uplift people through showcasing the realities that they live in,” said Smith. “Not giving up on the South is not an endorsement of those who do harm, but an affirmation of those who have been harmed. The reality of the South is that we are constantly haunted by our own past, but we must acknowledge it to have a better future. To me, Southern Gothic has been an opportunity to reckon with the complicated legacy of the place that I call home.”

“Southern Gothic” will be on display in the Gutman Gallery in the Hood through Feb. 27. A recording of the “Space for Dialogue Gallery Talk” will be available on the Hood’s YouTube channel.