Updated 3:45 p.m., Oct. 14, 2021.

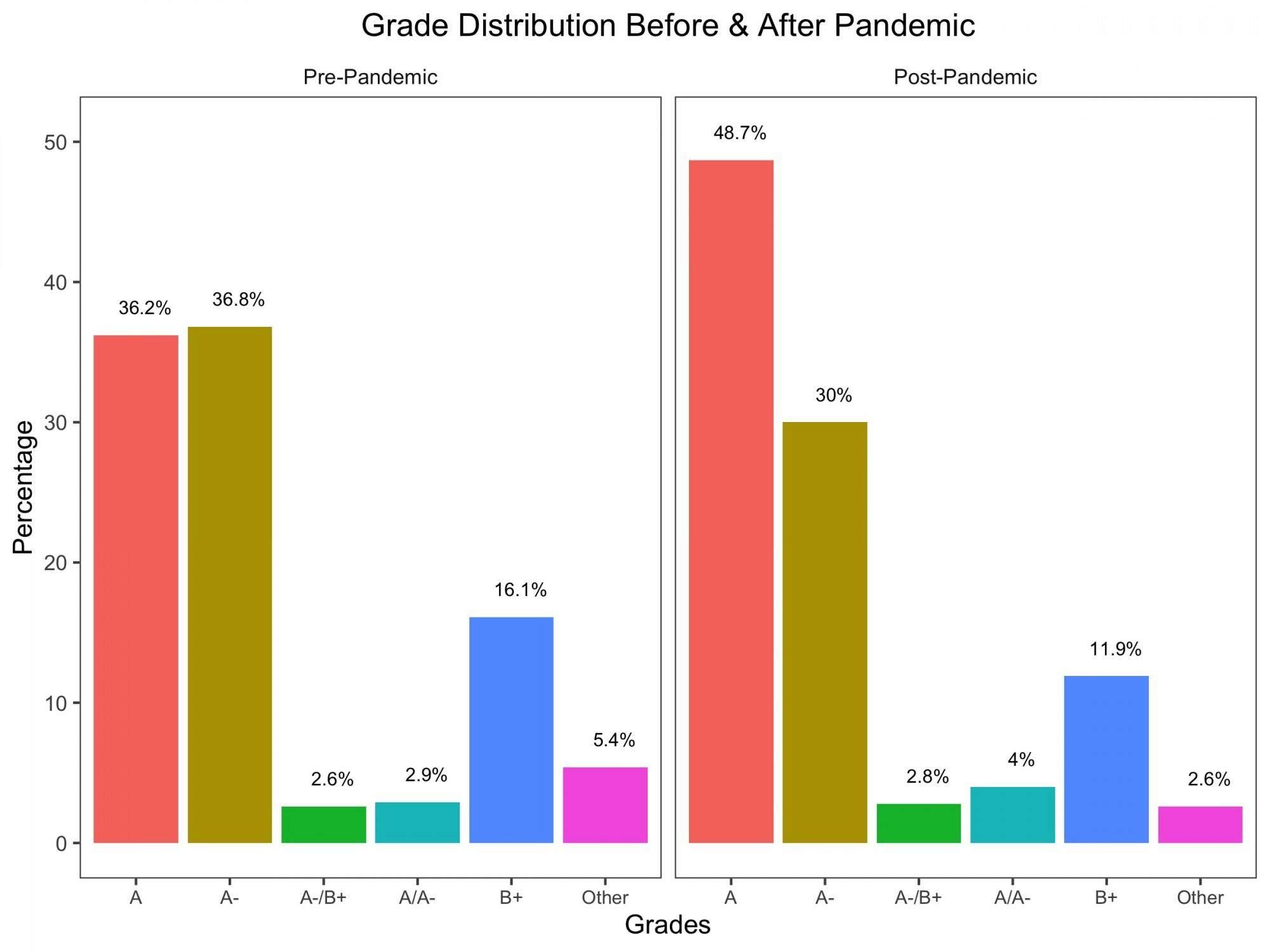

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with a significant increase in the number of students receiving top grades in their classes. According to Office of the Registrar data analyzed by The Dartmouth, the proportion of classes with an enrollment of at least 10 students that had a median final grade of “A” rose from slightly above 36% in the three terms preceding COVID-19 to almost 49% in the three terms after the outbreak that saw normal grading. The pandemic also correlated with a drop in the number of classes with “B” and “B-” medians, from 5.4% of classes before the onset of COVID-19 to 2.6% in the three terms after.

The number of recipients of academic honors has also increased as median grades went up. The College awarded the Phi Beta Kappa sophomore prize to 36 members of the Class of 2023 in 2021, up from 14 in the Class of 2022.

Classes with under 10 students do not have publicly available medians and were not included in The Dartmouth’s analysis. The terms before the pandemic included in the analysis were spring 2019, fall 2019 and winter 2020; the terms after the pandemic included were fall 2020, winter 2021 and spring 2021. Spring 2020, the first term of the pandemic, saw universal credit/no credit grading.

The Dartmouth College Organization, Regulation, and Courses Archives indicate that over the last year, the grade point average cutoff for summa cum laude honors rose from 3.93 to 3.94; the cutoff rose from 3.83 to 3.86 for magna cum laude and 3.69 to 3.72 for cum laude. These thresholds have trended upwards since 2012 — archives from the 2011-2012 academic year placed the year’s cutoffs at 3.90, 3.78 and 3.62, respectively.

These increases come after decades of slow but steady pre-pandemic grade inflation at the College. Previous reporting by The Dartmouth, based on an internal report obtained in 2019, showed wide disparities between departments in average grades and an increase in "A" and "A-" grades compared to all other grades between 2007 and 2018.

Some students attribute the upward trend in grades during the pandemic to a decrease in rigor while classes were held virtually. Emily Sun ’22 said her classes “definitely got easier … on a couple of fronts” with the move to online classes this past year. She attributed her easier schedule to the increased free time she had due to the elimination of in-person factors such as walking to class and social obligations, leaving her with more time to study.

Sun added that her professors were more accommodating, offering open book exams intended to head off cheating.

Community standards and accountability director Katharine Strong wrote in an email statement that “the number of reports [were] similar to years past,” but that there have been “increases in the numbers of students included in those reports in the last two academic years.”

Other students said they did not notice significant changes in the difficulty of their classes’ curriculum. Isabella Yu ’23 said that her professors in spring 2020, the first term impacted by COVID-19, were “more flexible” than usual, but added that “the difficulty of the class material” in later terms was similar to a normal term. Yu said she also had added challenges, as she was living in China while taking virtual classes and had to navigate time differences to attend her classes and office hours.

History professor Jorell Melendez-Badillo said his teaching style “changed greatly” as a result of the pandemic.

Instead of assigning traditional papers at the end of the term, Melendez-Badillo said he tried to foster a sense of community in his online class by having his students work on a collaborative project or an “interactive timeline.” He added that since shifting to an in-person setting, he considers his classes “more demanding in terms of participation from students, not from assignments,” adding that he has not increased the difficulty of his content, but has increased his expectations in the classroom.

Conversely, writing professor Ellen Rockmore said she believes her classes were not noticeably different during the pandemic; she noted that she already used Canvas before the shift to remote learning. Rockmore added that she may have had an easier time adjusting with her 16-person courses, noting that larger courses could have faced more difficulty in conducting class discussions and feeling “like they’re a part of a community.”

The changes witnessed during the 2020-2021 remote school year have caused some students to wonder whether the same leniency will exist with the return to in-person classes. Sun claims she has “less time on [her] hands” to complete a similar workload since returning to in-person classes.

Sasha Kokoshinskiy ’23, who took a gap year during the virtual year, said that while his classes feel “harder” coming off of a gap year, he has felt that the actual difficulty of his classes is the same as they were pre-COVID-19. He added that his professors, in an effort to aid their students with the transition back to in-person learning, still conduct their office hours over Zoom even though classes are in person.

This article has been updated to include the specific terms before and after the pandemic included in the analysis.