On Oct. 13, clay and textile artist Anita Fields participated in a live conversation hosted by the Hood Museum of Art curator of Indigenous art Jami Powell. The conversation focused on Fields’ practice as well as her work, “So Many Ways to Be Human,” which is part of the exhibit “Form and Relation: Contemporary Native Ceramics” that runs from January 2021 to July 2022. Six Indigenous artists are included in this exhibit, which focuses on themes such as community, land, gender and responsibility. Dartmouth ceramics studio director and instructor Jennifer Swanson facilitated the talk.

Fields, who studied painting at Oklahoma State University’s Institute of American Indian Arts, created thirty small figures for the Hood that were installed on a wall in diamond formation. Powell noted that this shape allows viewers to see the multiplicity of the installation.

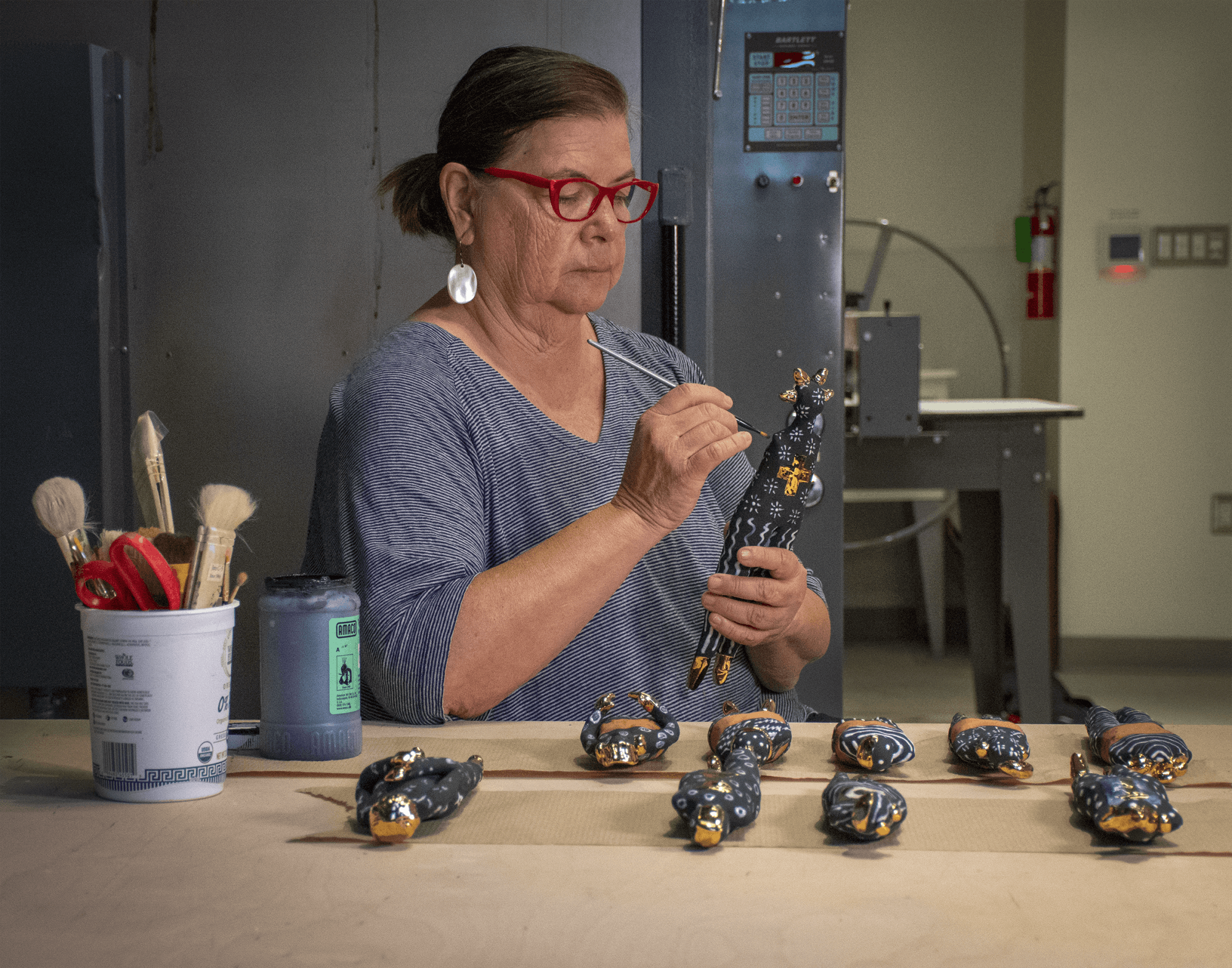

“These figures are not necessarily gendered, they’re pretty abstract — some have arms some do not, some have hair some do not, some have textiles wrapped around the center of the figure some do not,” Powell said. “The conversation you’re able to have when you put them all together is the most interesting to me.”

These small figures are mounted and displayed on a mauve wall, with black and white bodies contrasting the gold leaf accents that surround their various body parts. With clothing-like accents made of various materials added to only certain figurines, each has intentionality in design, appearance and positioning.

Powell noted the importance of having as many as thirty figures exhibited at once at the Hood.

“I have been following Anita’s work for decades, and she creates these figures and has really only ever had five or six displayed together at any one time,” Powell said.

Lily Gray ’24, who has visited the exhibit, noted how the seriality of the figures added to her understanding of the work.

“The artist’s ceramic figures are beautifully intricate and unique,” Gray said. “Each doll is compelling and interesting individually as well as with the collective.”

Fields used a variety of materials for the figures, including bits of cloth, gold leaf and paper, some depicting a map of Osage county. Fields noted she and her daughter would keep any information they found about Osage people, which helped her in the construction of these figures.

“I want to dispel the many myths that were written about us,” Fields said.

As a member of the Osage Nation, Fields spoke about how the figures explore dualities within the Osage culture.

“There are so many ways to be human, so many ways to be who we are . . . I have found clay to be so representative of a human being,” Fields said. “The kind of words you use to describe clay are words you can use to describe human beings.”

Swanson asked Fields about the intentionality behind the figures’ doll-like qualities; Fields responded that she does not think of them as dolls, but rather as figures.

Many of the figures are not realistic— some do not have arms — but Fields emphasized their representational value.

“I do not see them as missing something, I see them as representing the human spirit,” Fields said.

Fields’ other works in “Form and Relation” are the landscape “When Referencing the Earth and Sky,” which is now part of the Hood’s permanent collection, and the ceramic sculpture “Reconstruct, Conversion, Here.”

Fields said the landscape piece was inspired by her travels with a group of Osage people.

“It had a really profound impact on how I started to think about landscape,” Fields said. “Landscape holds memory of the cultures who were first there: who lived there, who left there.”

Fields’ noted in the talk that her love of material is central to her practice, dating back to her grandmother teaching her how to sew. Her work is also inspired by traditional Osage clothing and Osage ribbonwork.

“I can use those kinds of items as metaphors . . . when trying to translate how beautiful our culture is,” she said.

Fields touched on the other recent work she had done, explaining her creation of a bullhorn to represent the need for change illustrated over the last year. The inside of the bullhorn is dusted with gold lead to represent the importance of the information being represented as Fields hoped to encourage viewers to examine what is going on in the world.

Within the last ten minutes of the conversation, the talk was opened to questions from the public. Many were specific to individual figures from “So Many Ways to Be Human,” such as questioning the intentionality of positioning behind the one holding up their fist and another with one gold foot.

Fields also discussed another of her art series, a collection of purses. Inspired by a purse that was gifted to her by her grandmother, she thinks of purses as representative of what we carry. This collection reflected on the many ways to be human, a common theme seen also in “So Many Ways to Be Human.”

When interviewed, Powell talked about how this event originally intended to bring Fields to Dartmouth campus for a live interview and workshop, explaining how COVID restrictions halted these plans and caused the change.

“Originally the plan was to have Anita come to campus and be here in person, and she was going to do the conversation in the galleries but also to have an in person workshop in the ceramics studio in the Hopkins center for the arts,” said Powell. “With the delta variant and being unsure about traveling, we decided to just move to a virtual program for the conversations and connections, but I think still hope to bring Anita to campus to do an in person workshop.”

Elle Muller is a ’24 from Tucson, Arizona. She is double majoring in English and creative writing & theatre. At The Dartmouth, she served as the news executive editor for the 180th Directorate. Before that, she wrote and edited for Arts. In addition to writing, Elle is involved with dance and theatre at Dartmouth.