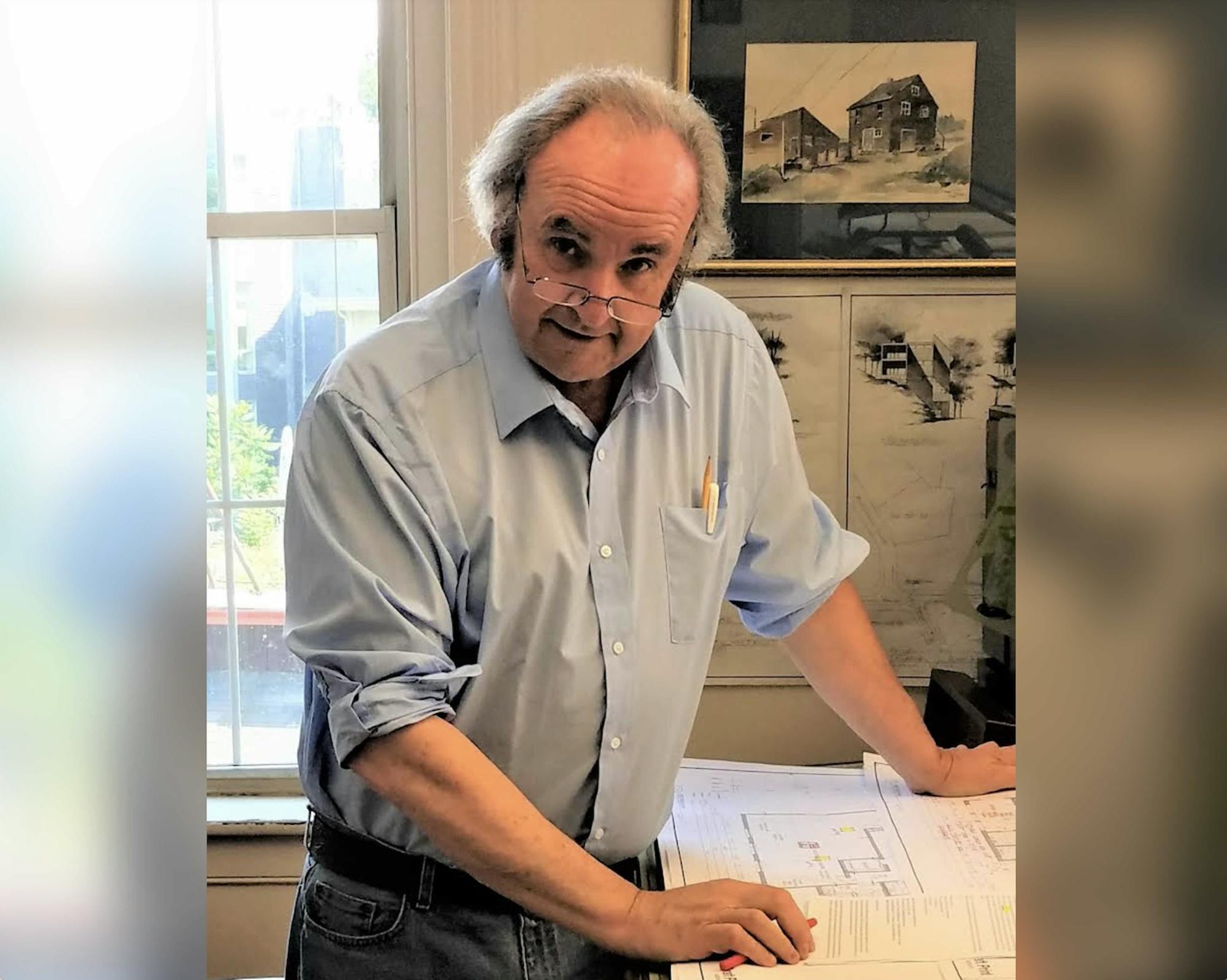

Frank J. “Jay” Barrett Jr. has always had a passion for architecture and a love for the town of Hanover. As a former Hanover Historical Society president and an architect by profession, Barrett has himself made contributions to chronicling the town’s history, even recommending buildings to the National Register of Historic Places. As a writer he has thoroughly chronicled Hanover’s rich history in the three volumes he has already published on the history of Hanover.

In an interview with The Dartmouth, Barrett discussed his experiences as an architect and how his interests in historic preservation and restoration have led him to publish his fourth volume on the history of Hanover. The book, titled “Lost Hanover, New Hampshire,” is slated to be published Monday.

What originally inspired you to write about the history of Hanover?

FB: I was a very young boy growing up in Hanover, and the son of an architect, so I’ve always enjoyed the history of the buildings. I’m 68 years old now, but I can remember watching buildings being moved from the seat of my bicycle during the summer months, being taken down, new ones being built — and at a very early age I knew that I, too, wanted to be an architect like my dad.

I’ve just always been sort of watching — not only the built environments around the College and the downtown village, but also the natural environments. I grew up on Mink Brook, so I was always watching the changes of the land, and was always very interested in the history of the land. That’s what inspired me to want to do a book on the lost buildings that have come and gone and the stories associated with them. It’s actually my fourth pictorial history of Hanover.

How is “Lost Hanover” different from your other three volumes?

FB: The first three were strictly pictorial histories. Hanover and Dartmouth were very fortunate in that the community was very well-photographed over the years. So the first Hanover book I did was in 1997. It sort of looks at the College and downtown from about 1890 to 1940, which is when the College and downtown went through a tremendous amount of change.

The second book I did on Hanover, I did in 1998, which covers all the rural parts of Hanover. That was very interesting because once you got beyond the College and the Village at the College, as it was once known, it really became hard to find images. But I did. And then the third one, published in 2007, was just a whole bunch of stuff that I hadn’t had the chance to use in the first two books.

This book — “Lost Hanover, New Hampshire” — I originally wanted to have the title, “Lost Hanover, New Hampshire at Dartmouth College” because it just focuses on the campus and the downtown village. I think it’s got to be 89 images and a 50,000-word text, and it deals with the earliest buildings that came and goes right up to the demolition of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital about 25 years ago — and includes a lot of stuff in between, telling the stories of the buildings and related institutions. There were just a lot of other buildings that were great buildings that have come and gone.

How has your experience in both historic preservation and restoration impacted the book?

FB: As an architectural historian and preservationist, I’ve put a number of buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places. That involves research, and it involves pretty exacting language in describing a bridge or a building — how it was built, the materials, et cetera. I was also a little bit limited by the fact that the history press willing to publish this did give me a limit of 50,000 words — I would have enjoyed writing more words — so I needed to write in a way that moves along and told the story, so to speak, without getting overly down in the weeds with description. It was about striking a balance.

What was the most difficult part of the journey to publication of “Lost Hanover”?

FB: Selecting the images. Between what I’ve collected, and what is in the collections at Rauner Library, there are just a lot of great images. Being an architect and being very visually-driven, there were some hard choices that I had to make as to what images to use and what images to unfortunately not use, so that was a real hard one.

What do you hope readers will take away from “Lost Hanover”?

FB: I think just a general appreciation of architecture and local history. One of the things that is very apparent in my book is describing how buildings go in and out of style. Former Dartmouth President Earnest Mark Hopkins purged the campus area of a lot of Victorian-era buildings and sort of replaced them with nice Georgian, Colonial-revival buildings.

I can remember the Hopkins Center for the Arts being built as a young boy — I’ve always really enjoyed that building for a variety of reasons, but by the 1980s, 1990s, it was a building that was underappreciated and out of style — people were just sort of turning against [post-war modern architecture]. Thankfully, the College has taken good care of the Hopkins Center, and what changes they’ve made to it over the years have been very sensitive to the original architecture of the building. But the style of buildings comes and goes, the needs for various buildings come and go, and that’s especially true in this book.

What are your writing goals for the future? Do you have any other works planned?

FB: I’m doing a lot of architectural work in Claremont, New Hampshire, which is about 25 miles south and was once a really vibrant mill community. It’s got lots of tremendous architecture left — even though for the past 30 or 40 years the community has been on hard times, it’s rebounding. You can just tell at one point how much wealth there was in that community due to manufacturing. I’d like to do a good architectural history of Claremont because you can tie it into so many other stories — manufacturing, transportation, advancements in technology — more so than what occurred in a community like Hanover.