This year's Manton Foundation Annual Orozco Lecture on The Epic of American Civilization murals, painted by José Clemente Orozco on the walls of Baker Library, was delivered by Ithaca College art history professor Jennifer Jolly. The talk, which took place this past Thursday over Zoom, examined the 1930s work of artist David Alfaro Siqueiros — a key figure alongside Orozco in popularizing Mexican mural art in the United States.

The overarching theme in Jolly’s lecture was the importance of critical engagement with images. Jolly argued that images will only “seduce” viewers if the viewer lets them, and that people should not give images the power to do so.

“We don't have to buy into the worldview that somebody puts before us,” she said. “What we really need is to always recognize our ability to critically engage, to step back and to walk away.”

Jolly began the lecture by detailing her interest in Siqueiros. After focusing her PhD dissertation on Siqueiros’s work in 2003, Jolly was motivated to study Latin American artists and has done so now for the past two decades. Events such as the Zapatista Rebellion of 1994 — a Mexican uprising in response to the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement — inspired Jolly to center her research on the effects of U.S. foreign policy on Mexico and Latin America.

As an outsider, Jolly said that she sought not only to better understand the detrimental effects of NAFTA abroad, but also to share and spread her findings.

“I wanted to be part of educating this new generation of students in the history of our nearest neighbor, Mexico, and Latin America more broadly, too, because the United States has such a complex and problematic relationship with Latin America,” she said. “In part, what sustains that seems to be the fact that so few U.S. citizens know anything about Latin America, and so I really wanted to be part of changing that.”

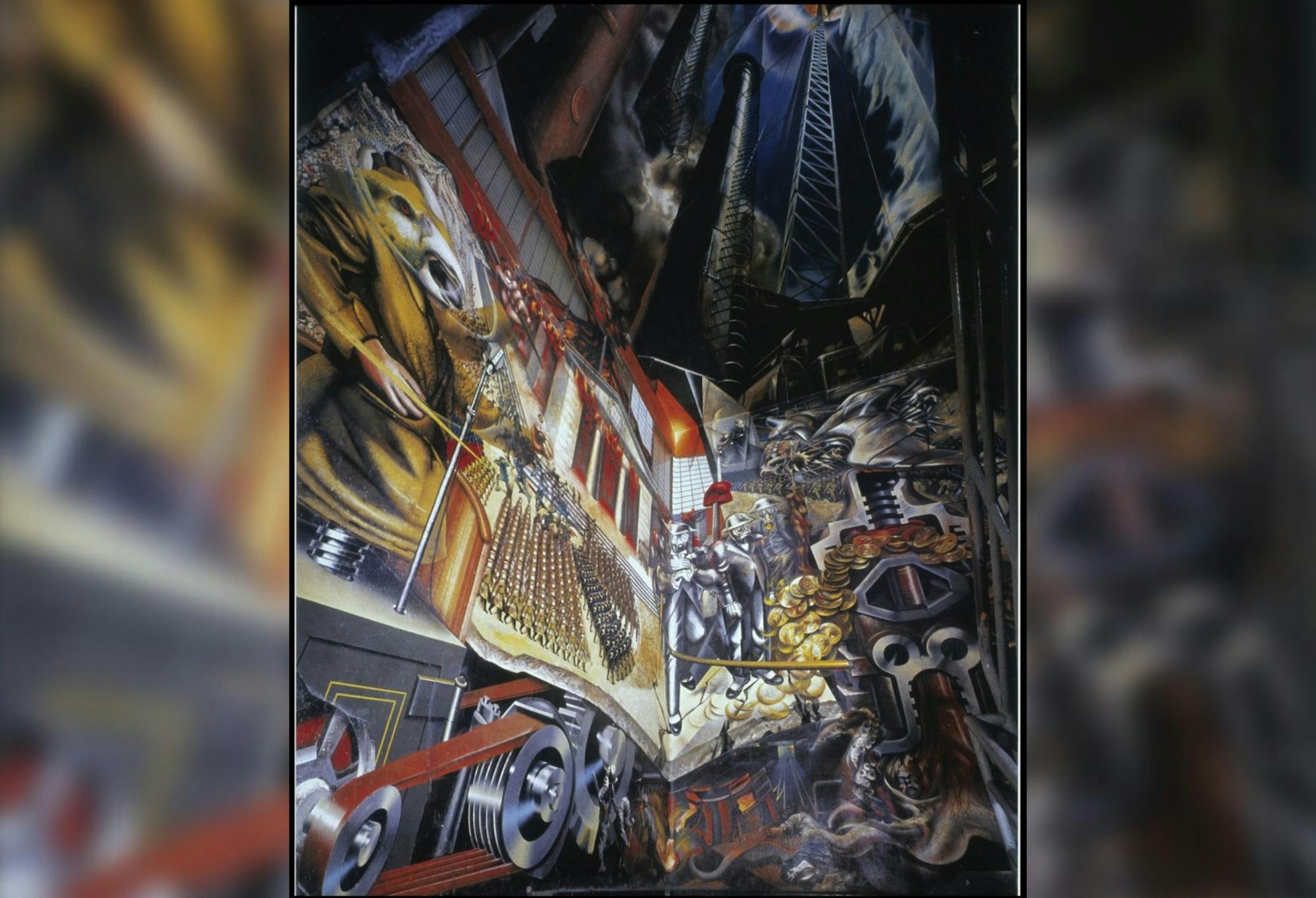

Throughout the lecture, Jolly analyzed the handful of projects Siqueiros undertook in the 1930s, focusing specifically on his approach of using linear perspective to engage his viewers and create dialogue around his murals. Jolly also delved into Siqueiros’s use of anamorphosis, a technique that distorts an image or other artwork such that it can only be viewed in full at a specific angle.

“Siqueiros was working with this idea of distorting images to try to make us work to resolve them, and this process was one of his strategies for swaying us to his point of view,” she said.

Dartmouth art history department chair and previous Orozco Lecture speaker professor Mary Coffey said she was drawn to Jolly’s lecture because it focused more on the actual form of the mural rather than just Siqueiros’s communist convictions. Coffey — a scholar of modern Mexican visual culture — said that Jolly’s lecture put the Orozco murals in conversation with other topics.

“Siqueiros and Orozco are artists who are most responsible for establishing the debates about muralism as a political art form and its relationship to the viewer and architecture,” she said. “It is important for Dartmouth to get an understanding of Orozco's peer set and how they are kind of all talking to each other, not only in what they say and what they write, but also in what they paint and how they paint it.”

Jolly said she became interested in specialize her studies on Siqueiros during her college years, when she grew curious about the relationship between art and activism. She is particularly drawn, she said, to artists who put activist work and art in conversation.

“In particular, I turned to Mexico because in the context of the Mexican revolution, it really became the norm for artists to be engaged, in one way or another, with questions of art and social transformation and how art can contribute to larger social and political processes of change”

Per Jolly, the focus of her lecture was not to celebrate Siqueiros, but rather to examine his work and question themes of art and activism. She analyzed the conditions under which art spurs change and discussed Siqueiros’s interest in sharing art with the purpose of inspiring actionable change.

Curator of academic programming at the Hood Museum of Art Amelia Kahl ’01 noted that although the Orozco murals are almost 100 years old, they continue to contribute to Dartmouth not only aesthetically, but also in terms of intellectual and academic life on campus.

“The murals were part of Dartmouth having an artistic identity and of commissioning artists,” Kahl said. “Dartmouth has the Artist in Residence Program, and Orozco was the second artist in residence in the 1930s. And so, to me, that shows the College’s commitment to contemporary artists, diversity and being open to different ideas.”

Kahl pointed out that as the College continues to teach virtually, the Hood has found alternative ways to showcase Dartmouth’s public art collection in a way that remains accessible to the community. The Hood recently launched a 3D virtual tour of Orozco’s murals which allows audiences to both take a closer look at the panels and compare them to Orozco’s preparatory drawings.

Coffey emphasized the significance of the Orozco murals and encouraged students to explore the public art collection on campus through these virtual events.

“Scholars are all helping us to appreciate [the murals] as an avant-garde art form that has a lot of nuance, but also a lot of contradictions,” she said. “These lectures are helping us have a much more sophisticated and historically accurate understanding of the contributions that these artists made to western art, political art and how we understand the relationship between art and the viewing subject.”