From April 5-11, the Hopkins Center for the Arts held a symposium that brought together acclaimed speakers to discuss the issue of police violence and its ties to racial injustice. Since the symposium, Derek Chauvin’s trial has ended with his conviction of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. However, the end of the trial did not mark the end of police violence, nor the discourse surrounding it, in America; it remains an ongoing issue. This week, The Dartmouth sat down with art history professor and symposium co-organizer Mary Coffey to ask her to reflect on the event as well as provide insight into what students can do to remain engaged in the fight against police violence. These answers reflect Coffey’s personal views, and she noted that she avoids pushing any specific views onto her students.

What led you and African and African American studies professor Tricia Keaton to decide to organize the symposium at Dartmouth during this time?

I think I was responding to [Keaton’s] initial call. She sent an email around to a bunch of professors to put together something on the problem of police violence. From the very beginning, we were interested in having people in our community — and we worked with students on this — weigh in on this issue. For the past several years, we've been undergoing a kind of consistent set of protests, outrages and perspectives on the problem of police violence in the United States. But this is a global problem, to such an extent that the United Nations is acknowledging it. And maybe there's a way that we can do something to think about this, not only in the national framework, but also more globally to do some comparative thinking or to think about how police violence manifests in other national frameworks.

Many of the panelists spoke about the lack of effectiveness in pushing for police reform or reallocating of funds due to the power possessed by legislative bodies to block these proposals, and some spoke about the complete abolition of the police system as an alternative. Do you think pushing for reform or abolition is more effective at this point?

My personal belief is that reform is not a viable approach to addressing the problem of police violence because reform tends to focus on techniques and symptoms. But it can't really address the sort of structural problems that produce the forms of racialized policing, surveillance and criminalization that result in violence.

So I have, for a while, been invested in the idea of defunding. I always try to explain to anyone who's really alarmed by that term that defunding the police means, at its simplest level, reallocating some of the massive amounts of state and local financial investment that go into policing into other social services that over the past several decades have been stripped of funding and suspension and support. My personal belief is that abolition is what we should be moving towards. I also see abolition as a creative reimagining of our world — you have to be able to imagine a world in which policing doesn't exist or doesn't need to exist, at least according to the things we think today, in order to address that problem.

As the Derek Chauvin trial has ended and we mark almost a year since the protests following George Floyd’s death, how do you suggest people remain engaged and determined to continue the fight against police brutality and racial injustice?

I think there's a significant part of the American public who are going to say, “yes, justice has been served. And now we're turning a corner, and this will stop happening.” And I would argue that with Chauvin, there should be consequences for his homicide, but the question of what real justice looks like is something very different. It would have been horrific if he'd been exonerated in the trial. That wouldn't have been anything close to justice, but his going to prison, if that's exactly what happens to him, doesn't necessarily bring any real justice to [Floyd’s] family. It doesn't mean that we won't be in this situation again and again and again, because nothing's really been addressed at the systemic level.

So, how to keep people's attention on this is you have to keep having these conversations with the people we know who don't agree or who don't see the issue. And I think we'll have many opportunities for that because we will continue to have police murders. And we will continue to have kind of spectacular, public, clinical debates about those murders. And so, this is a conversation that's not going to go away on its own. And then it becomes the job of those of us who think this is important to be consistently trying to provide people with the information that they might need to come to a more informed conclusion about policing.

Is there anything else you would like to add about the symposium or the future of fighting against police violence and brutality?

I felt like there was something powerful and amazing in every panel; I just really learned a lot from them. I think some of the big takeaways are this simple observation that the bad apple argument — and even the spectacle of police coming out and testifying against Chauvin — is really fundamentally about shoring up the police. And I thought Simon Balto’s observations about how reform often ends up exacerbating financial and economic investment in policing, despite the fact that it doesn't generate any measurable or meaningful outcomes, is really important. It was helpful for me to think about why that can actually be counterintuitive, like actually investing in those forms of reform can often redirect more money into the police route than actually reforming anything.

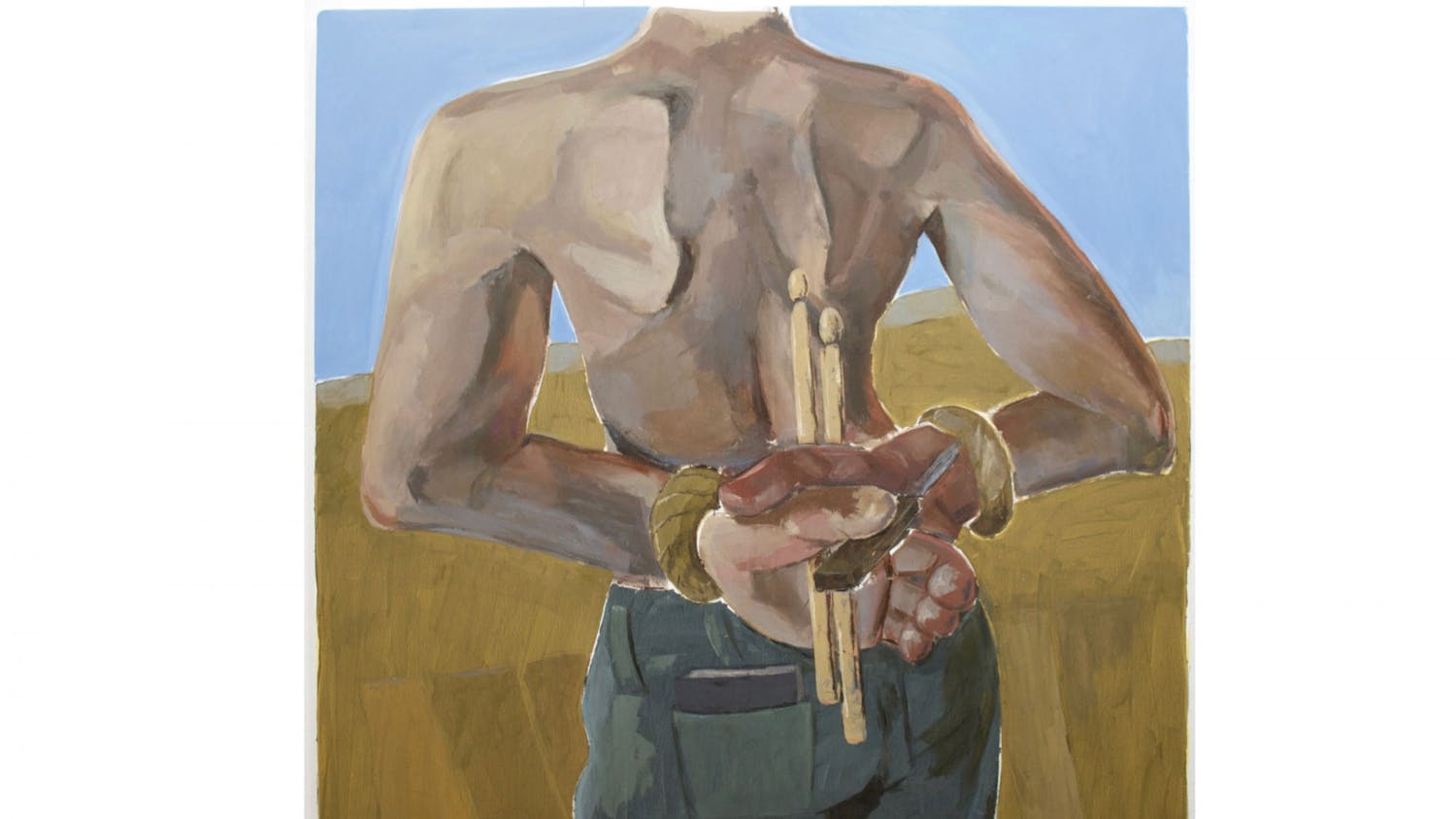

I thought that Andrea Ritchie and Nikki Jones, both their presentations, were just unbelievable and incredible in terms of helping us to understand just how intensified and dangerous policing is for women and LGBTQ+ people and children. I learned so much from the international panels about the form of policing in France and the role of the ID checks as the kind of primary tactic for just constantly harassing and surveilling and criminalizing people of color. I learned a ton about how this plays out in the post-colonial framework of Nigeria and Uganda, thinking about colonialism rather than slavery as the kind of key historical framework. And I really enjoyed all of the artistic presentations because one of the questions raised by this moment we're living in, where people are circulating images of murdered Black and brown people all the time, or people from Latin America in cages, as part of liberal or even progressive politics, is, “what is the impact of that imagery on the people who see themselves in those in those bodies? And what can art do to combat that?”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.