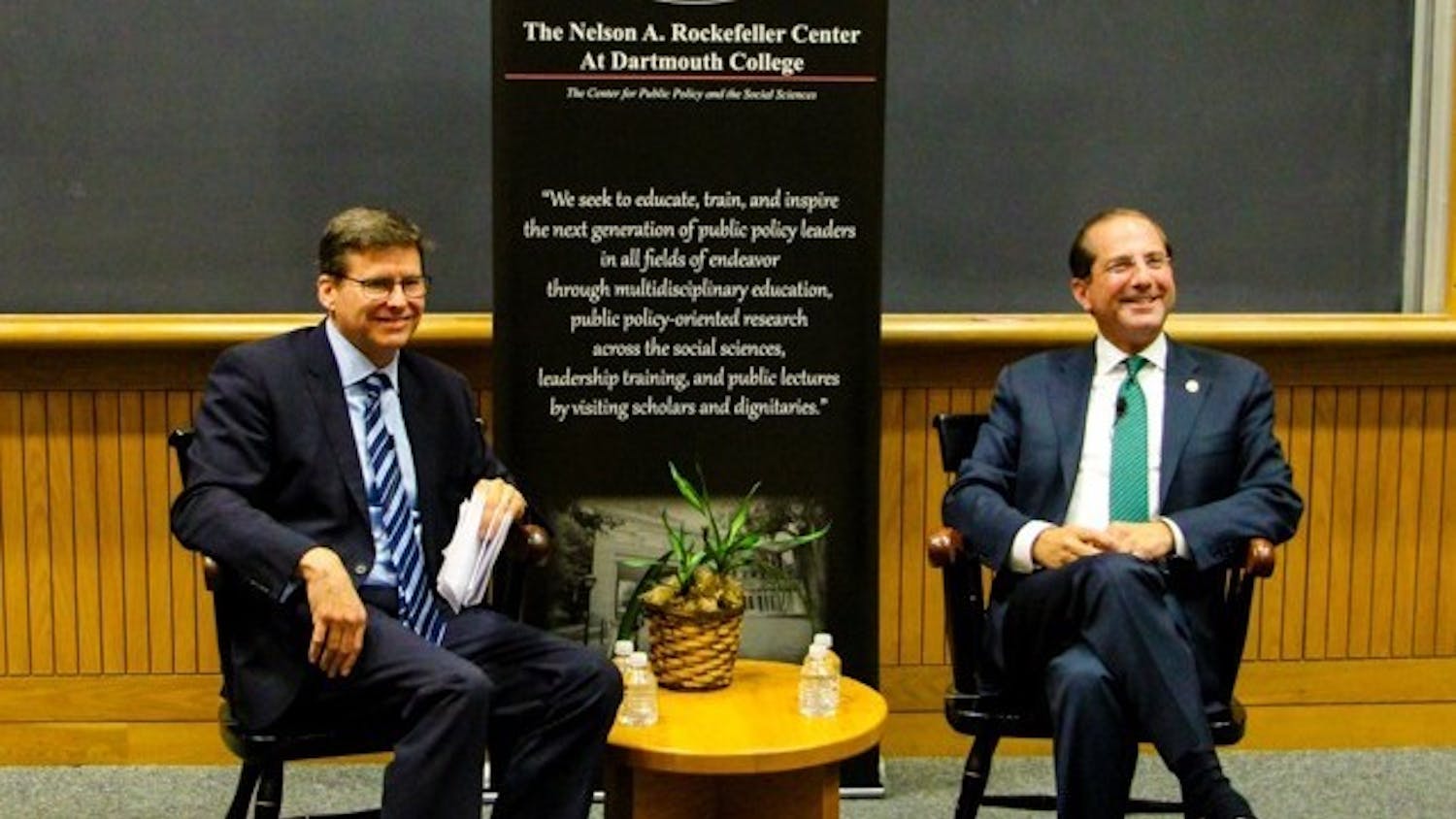

Dr. Daniel Lucey ’77, Med’81, a professor of infectious diseases at Georgetown University Medical Center, has been studying infectious diseases for nearly 40 years. Lucey has worked to develop front line responses to public health crises including SARS, swine flu and Ebola, and he oversees an exhibit on epidemics at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

Lucey sat down with The Dartmouth to talk about his research on the new variants of COVID-19, the threats these variants present to the U.S. and Dartmouth community and how to prepare for them.

You have studied infectious diseases around the world since 1982. How big of a concern are these new COVID-19 variants, and why?

DL: These new COVID-19 variants have actually been here for months — we just haven’t discovered them. There are more variants that have not been discovered but are already present, including in the United States and multiple other places around the world, which are a great concern.

I’d say we should be concerned about this new strain for several reasons. One is that they are more contagious than the current worldwide non-variant coronavirus. We know that for the variant that was first found in the United Kingdom and the variant that was first found in South Africa. I think we will have strong evidence of increased contagiousness in the variant that was first found in the northern Brazilian city of Manaus and in the Amazon region, but again, there are more variants that are being discovered all the time.

According to a report last week from South Africa, the very first vaccination in Africa was less effective in preventing infection than that same vaccine was in a study in the U.K., which includes the U.K. variant. So some vaccines are still working against some of the variants, but some are not.

We should also be concerned because some of these new variants can reinfect people who are already infected and have recovered. That is very, very bad news because for individual patients, they may become more ill and/or die with a reinfection from a variant. But also, it affects this concept of a so-called “herd immunity,” a phrase I really don't like at all — I prefer to say “community immunity.” The idea is that if a large enough percentage of people in the population have been vaccinated and/or have recovered from an infection, then the virus won't be able to spread wildly like it does before anyone has immunity.

You’ve had experience fighting many different pandemics and viruses over the decades. Can you draw correlations with other infectious diseases you've seen mutating in the past?

DL: Well, the first analogy that most people think of, myself included, which I think is an imperfect analogy, is influenza. So we know that each year influenza viruses mutate, and that's why we need to change the vaccine every year. In addition, there are now at least four types of influenza viruses, which we call H3N2, H1N1 and two influenza Bs that circulate around the world each year. We include all four of those influenza viruses in the flu vaccine.

I think that's where we need to go with COVID-19 vaccines immediately. I think we need to create new vaccines that are combination vaccines like the influenza vaccine, meaning combining several different kinds of what we call now variants. That's what we need to do to try to get ahead of this multi-variant pandemic, which is really what we're seeing now. It will hit the U.S. very hard — I would say by late March into April — in terms of the variant from the U.K. spreading.

We know that it’s more contagious. And two Fridays ago, the U.K. government publicly stated that their analysis shows now that the variant from the U.K. is now somewhat more deadly. So not only more contagious, but more deadly. That hasn't been said about the variant from South Africa or Brazil.

How would you assess the U.S.’s readiness in terms of the tools at our disposal to get this virus under control? Do we need to keep evolving our medical measures or personal protection?

DL: In my opinion, we definitely need to keep evolving to prevent infections, hospitalizations due to serious illness after the infection, patients needing intensive care being on breathing machines or ventilators and people dying. Some days in January, there were more than 4,000 Americans dying in one day. 90,000 Americans died in the month of January. So we need to do more.

I think you can see that in the new administration by the administration's efforts to vaccinate more people. President Joe Biden has set a goal of vaccinating 100 million Americans in the first 100 days of his administration. I think that that’s a minimum number.

But in my view, it’s very important to make sure people get the second dose of the vaccine. The U.K. and also the U.S. have recently said that the second dose could be given at a later time point than was shown through vaccine studies to be safe and effective. So instead of after three weeks or four weeks, maybe after six weeks is OK. From a scientific point of view, I’m against that. But I also recognize that we need to protect people as much as possible, especially if this U.K. variant is going to become predominant. As of Wednesday, the U.K. variant is in 33 U.S. states, so it’s more than half the states where this variant from the U.K. has been found.

What are the implications of these new variants for the Dartmouth community and other colleges looking to return to on-campus and in-person normalcy?

DL: I’d defer to the judgment of Dr. Lisa Adams and her co-chair of the Dartmouth-wide COVID-19 task force. All I can say is from a distance, it seems the Dartmouth community has had a very positive response in terms of keeping the level of transmission of the virus and number of people infected — both students and other members of the Upper Valley community — really quite low, particularly compared with some other universities and surrounding communities. I hope that Dr. Adams and others at Dartmouth will publish what they've done to offer a model of success for other colleges and surrounding communities.

I think that what applies to the United States as a whole, whether it’s in cities or in rural areas, applies to the Dartmouth community in terms of advent of these variants and their transmission.

So I think we need to be, if anything, more vigilant — although it's extremely hard to do that because people are very fatigued, frustrated and harmed economically by this pandemic. But if the variant from the U.K. is more contagious — and I think everyone agrees with that — it means we have to be even more stringent, if you will, in terms of our what's called “non-pharmaceutical interventions,” which is wearing a mask, or now some people are saying two masks, and maintaining at least six feet of distance.

What is something that you think most people don’t know about COVID-19, but should?

DL: One thing is that it is real. It is real, and it does kill people. Over 445,000 Americans are known to have been infected and died of COVID-19, which means there’s many more. And it might sound obvious to people in the Dartmouth community and to many people that the virus is real, but as you can see from behavior, particularly at the highest levels of the past administration, it wasn't taken as a real threat to many people.

I think that's still true — you see people not wearing masks at all. Even some of our lawmakers in the Capitol — you've seen the video, I'm sure, from Jan. 6 — during the insurrection, some of the lawmakers were offered a mask, and they refused to wear it. So that’s one thing, and it sounds perhaps too basic, but I think it's very, very important.

And it reminds me, by analogy, to when I first got off the plane in Freetown, Sierra Leone in early August 2014 to go work during Ebola. In Freetown, there were big signs in the airport and right outside the airport that said, “Ebola is real.” And I was mystified at the time.

So really, that’s it: COVID-19 is real, and the variants are coming. The variants are here. And they’ll be in the Upper Valley if they’re not already, just like they’re in California and Washington, D.C. and Boston and Chicago and everywhere else.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Correction appended (Feb. 5, 2021): A previous version of this article stated both that the president plans to vaccinate 100 million Americans in his first 100 days and also that he is aiming for 150 million people vaccinated per day. We have deleted the second, incorrect statement.