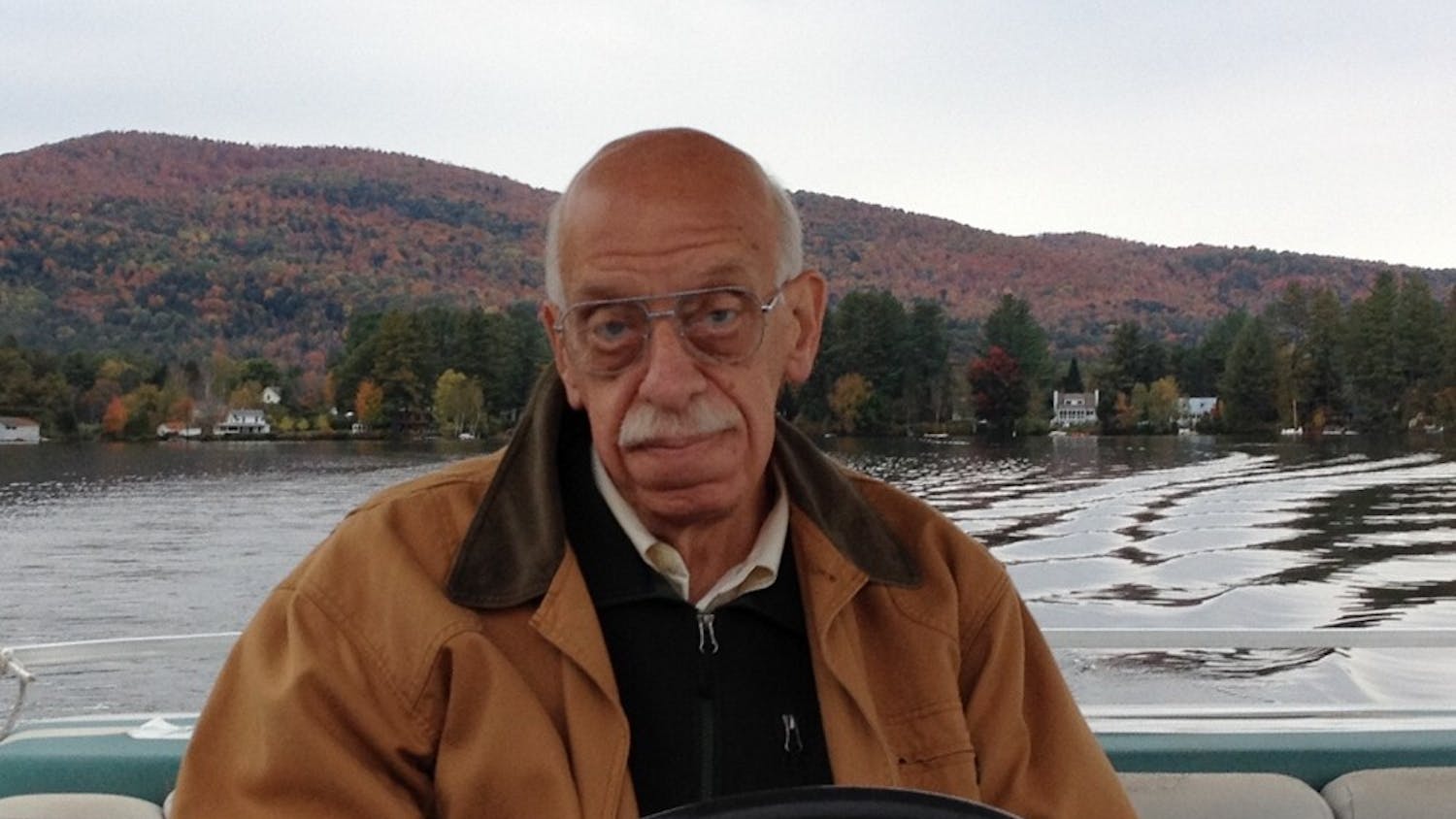

A prolific researcher and dedicated father and husband, Alan Ivan Green was known for his endless enthusiasm, innate curiosity, steady nature and kindness.

“He was a wonderful, warm, intense man who was one of the most curious people that I've known — a real scholar and someone who just was ready to make the most of every opportunity that came his way,” said Kathryn Kirkland, a fellow professor at the Geisel School of Medicine and Green’s friend and neighbor.

Green, who served as the chair of the Geisel department of psychiatry and professor of molecular and systems biology, died of cancer at the age of 77 on Nov. 26. He is survived by his wife of 37 years, Frances Cohen, his children, Henry and Isobel Green, and his extended family.

Green grew up in Norwalk, Connecticut, where he excelled in tennis and skiing. He graduated from Columbia University with a bachelor’s degree in history in 1965 and went on to receive a medical degree from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1969.

Green began his career with a fellowship at the National Institute of Health and an internship at the Beth Israel Hospital in Boston. Following a brief stint as the director of research for the White House Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, he began his residency in psychiatry at Harvard University in 1972. Delayed by a viral illness, Green finished his residency in 1981 and proceeded to work at Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Mental Health Center, before arriving at Dartmouth in 2002.

While at Dartmouth, Green served as an inspiration to many, including fifth-year graduate student Emily Sullivan, who worked in his lab for four years. Sullivan said that Green was an “incredible mentor and advisor” to her and the entire lab.

“He was an incredibly busy person, but he always took time to meet with us,” Sullivan said.

She added that when she wrote a grant this past year, Green took the time to walk through it line by line, helping her to “craft the story.”

“It just really meant a lot to all of us — the effort and the time he put in to help our own careers develop,” Sullivan said.

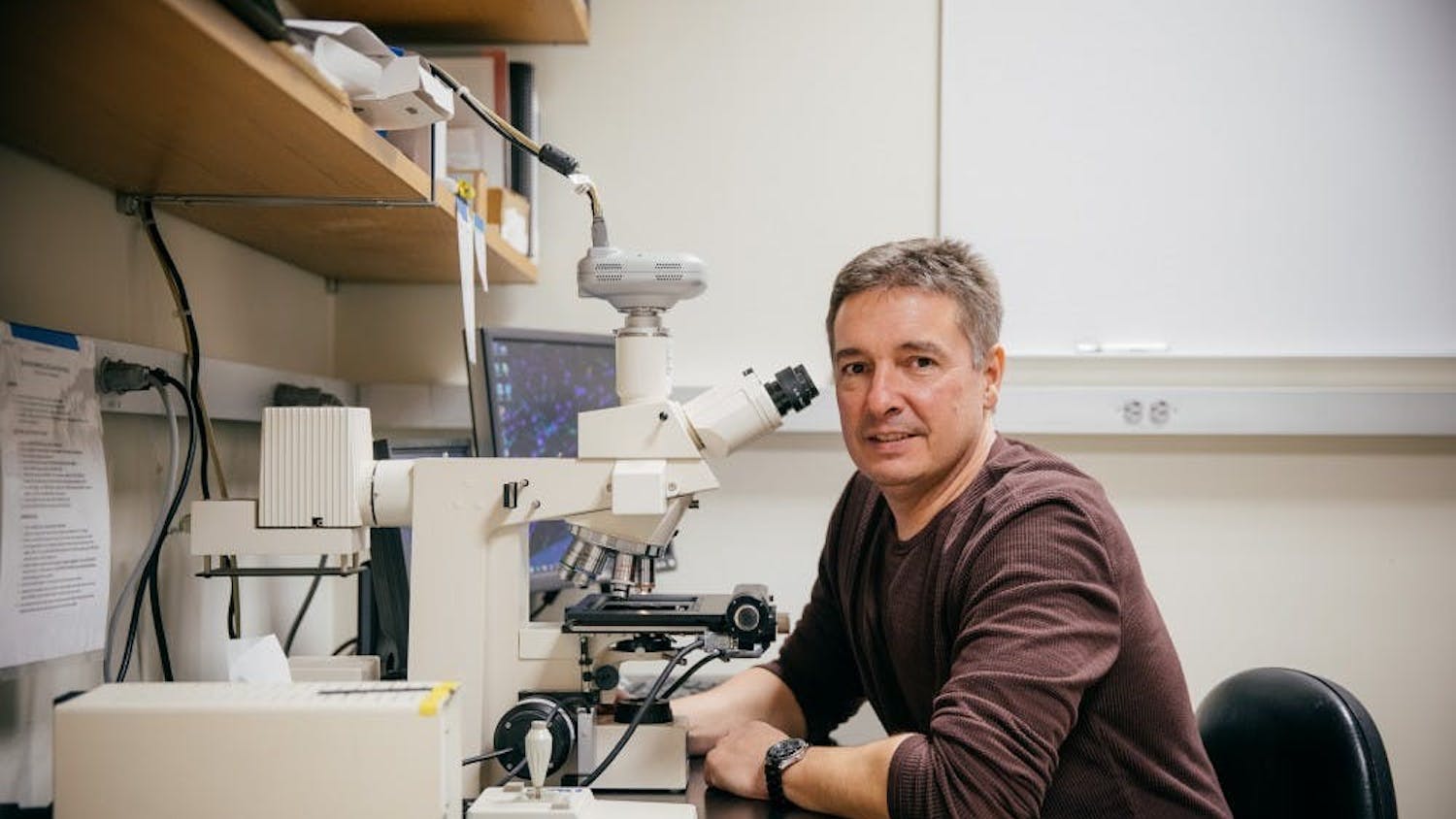

Geisel psychiatry professor Cornel Stanciu recalled that when he came to Dartmouth in search of a job, Green was there to help him through the process.

“I recall as if it was yesterday the day I was discussing my current position with him in his office,” Stanciu wrote in an email. “He pulled up a wooden chair next to [me]. ... He spoke from the heart about his life journey, challenges he overcame while dedicating himself to furthering the knowledge base of our field. His genuine personality helped me figure out my own values and to glean direction in my professional life.”

Geisel psychiatry professor William Torrey, who was a student at Harvard Medical School while Green was there as a faculty member, said that Green served as a role model both in his dedication to students and to his own work.

“[Green] just was interested in and excited about everything to do with psychiatry,” Torrey said. “He really believed in providing outstanding clinical care. He wanted the teaching program to be remarkable.”

Geisel molecular and systems biology and neurology professor Hermes Yeh referred to Green as a “ball of energy” when it came to scientific research. Yeh said he was especially curious about the relationship between schizophrenia and alcohol abuse.

“[Green was] just a consummate scientist,” Yeh said.

Torrey added that Green played a vital role in the development of Moms in Recovery, a program that helps parenting women deal with substance use disorders, and the expansion of the crisis and consult services at Dartmouth.

“He’d be at his desk at 11 o'clock at night at the hospital with the lights on,” Torrey said. “The residents would tell me, when they're on call in the hospital, they'd feel lonely, working their way through the night. But they'd see him there working too. And that helped them to feel like they weren't alone in this work.”

Outside of work, Green dedicated much of his time to his family.

“He brought passion to everything that he did,” Kirkland said “… He was equally personally engaged in both his devotion to the academic institutions that he was affiliated with and to his large extended family that seems amazingly close.”

Isobel Green said that her father “never seemed busy” and was always eager to spend time with her. If she wanted to go for a walk, chat or eat ice cream, “he was always up for it immediately,” she said. She added that Green loved ordering the smallest size of a classic sundae with vanilla ice cream, hot fudge and a cherry on top.

Henry Green recalled his father’s caring nature.

“He would often be the one to do dishes after dinner … so that everyone else could sit at the table and be talking. And I feel like that sort of encapsulates him,” Henry Green said. “… He would try to provide an environment where we could all blossom.”

Cohen, a lawyer, fondly remembered how Green would always attend her oral arguments when she was younger and how supportive he was of their children and their achievements.

Later in life, when Cohen joined a swim team, Isobel Green said her father would always attend the swim meets to cheer on his wife.

“She placed last every single time, but my dad was so beyond proud of her,” Isobel Green said. “I remember just standing in the stands, watching the swimming pool with him. And his face was totally trained on her and just lit up. I just thought it was very cute that he supported her … no matter what she did.”

In addition, Cohen said Green always tried to instill the value of getting “back up on your horse” in his kids. Isobel Green said that if she had any issue, her father would ask her about her next step and encourage her to put the past behind her.

“I did reach out to him whenever I was disappointed or discouraged just because he was such a good buoying force, and I'd always get off the phone with him feeling better,” she said.

In his free time, Green loved to dance, play music and write.

Kirkland called him “the best dancer in the Upper Valley prior to his death.”

“He could really cut a rug. … He could do anything from the waltz to the foxtrot to swing, to just rock and roll,” she said.

According to his wife, Green loved to dance to the Great American Songbook, Frank Sinatra and the Beatles. She said that since she has “no sense of rhythm,” Green would count out the beats for her when they danced together. She added that Green could play any song on the piano with a bit of practice.

Green was a prolific writer of both nonfiction and fiction, according to Kirkland. When Green contracted the viral illness in the ’70s, he took the time to write a novel titled “Rucker’s Rule,” though it was never published. He also loved to garden, Cohen said. He was particularly fond of dahlias, which his mother also grew.

Faith was an important part of his life as well. Green spent much of his spare time celebrating the Jewish holidays with family or talking to his rabbi at the Upper Valley Jewish Center.

Green’s funeral was held on Nov. 29 at 11 a.m. over Zoom, with a private burial afterward. His family then observed Shiva, a week-long mourning period in Judaism.