After a summer of historic racial reckoning, institutions across the United States have reflected on the roles they play in perpetuating racism in this country. Colleges and universities have tried to be especially vigilant in these reckonings. Princeton University has been one of the most visible institutions addressing its past: It recently removed former President Woodrow Wilson’s name from its School of Public and International Affairs and one of its residential colleges. A new residential college built in its place will be the first at Princeton to be named after a Black alumna. While the actions of Princeton and other universities undertaking similar efforts do not erase these schools’ pasts, they do represent important first steps in addressing years of racism within their walls.

However, Dartmouth has avoided doing the same. In fact, it continues to capitulate to the likes of one of its most prominent alumni, Theodor Geisel ’25, the American children’s author better known as Dr. Seuss. Though Geisel’s books are widely read, his career and the characters in his books are tainted by his contributions to racism in print media. Yet, Dartmouth still memorializes him on admissions materials and, most glaringly, through the Geisel School of Medicine. If Dartmouth is truly committed to standing up to racism, we must stop glorifying Geisel in our medical school and other campus spaces. Instead, it’s time for us to highlight other alumni whose work has done more good for the world.

Unsurprisingly, the seeds for racist aspects of Geisel’s career were sown even before his time at Dartmouth. He wore blackface in a performance in high school. He capitalized on the N-word and on racial stereotypes of Black and Asian people in the satire magazine Judge. He drew racist and anti-Semitic cartoons in the College’s satire publication, the Jack-O-Lantern. Geisel contributed to propaganda that denigrated the Japanese community in World War II.

It’s no surprise, then, that Geisel’s racism permeated into his children’s books. Though it is true that Geisel grew to disavow certain aspects of his early career, his books are still far too homogenous and offensive to be popularized. According to one 2019 paper in the journal “Research on Diversity in Youth Literature,” of the over 2,000 human characters Geisel created in his children’s books, only 45 were non-white; all 45 non-white characters were portrayed with offensive racial stereotypes. Even seemingly innocuous characters, such as the Cat in “The Cat in the Hat,” are argued by some to be inspired by blackface entertainers.

Proponents of Geisel often laud his work as having inspired millions of children, but at what cost? Yes, generations of kids learned how to read with his books. But portraying his nonwhite characters with racial stereotypes, such as a Chinese man in “And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street” with chopsticks and slanted eyes, fuel the racial biases that begin to develop in children as young as three years old. By targeting readers around the same time they begin reading, Geisel’s works undoubtedly contribute to heightened racial biases, and even racism, among his audience. At best, those infected with Geisel’s racism overcome it; at worst, that infection lives with them for the rest of their life, influencing every interaction they have with people of color.

While many would counter that Geisel’s rhetoric was reflective of the times, that does not erase the racist implications of his words. We don’t judge history’s racist characters by the prevailing attitudes of their times. Instead, when we critique historical figures, even those whose impacts appear beneficial, we must do so using today’s standards. That’s why recent efforts have tried to remove former President Andrew Jackson’s face from the $20 bill, or why Confederate monuments have been toppled across the South in recent years. And, that’s also why Princeton removed Wilson from its campus’ iconography. Though many will argue that his impact is far more positive, Geisel must not be held to a different standard. Paying fraternal homage to him as a Dartmouth alumnus isn’t a bragging right; rather, it shows how little Dartmouth cares about bettering its racist past.

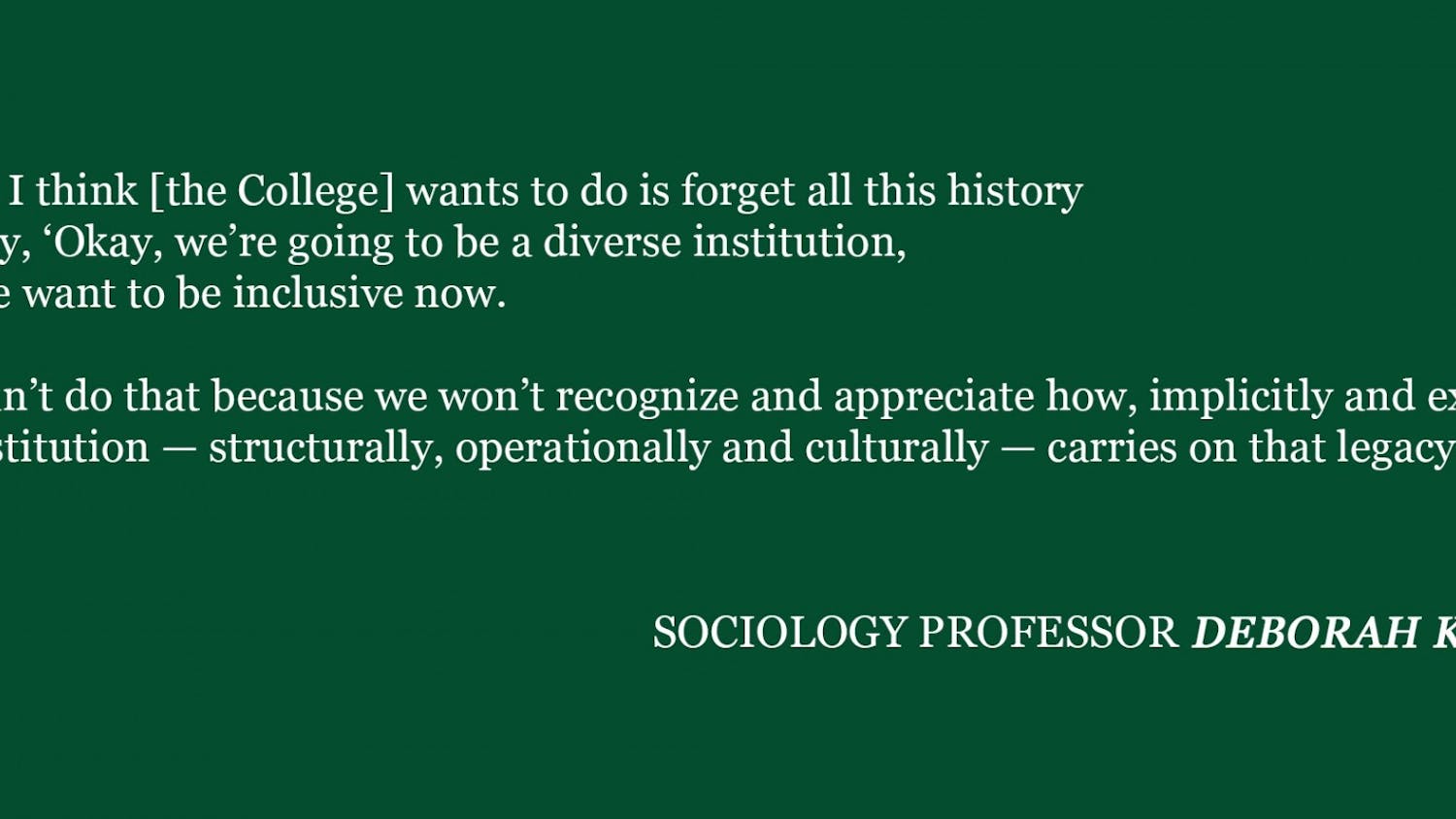

I say this knowing little will change. When the Dartmouth Medical School was renamed in 2012, the Geisel family was the largest donor in the College’s history. That kind of money speaks volumes about the company Dartmouth keeps and limits the chance for change. Nevertheless, we must not fall into the trap of unabashedly praising Geisel without recognizing the ugly history his work was born out of and the often harmful ways he contributed to children’s literature. While he never had the political power of Wilson, Geisel’s actions are no less responsible for the implicit racial biases of millions. Unless this institution wants to remain complicit in Geisel’s racist past, Dartmouth must take great pains to look within and break away from his legacy by removing Geisel’s name from the medical school and other campus spaces once and for all.