A few nights ago, I was up late, lying in bed and watching reruns of The Office. I was horrified. Jim and Pam were shopping for a new toothbrush for their daughter, Cece. “How reckless,” I thought, shaking my head in disgust while the sweethearts of one of America’s favorite sitcoms walked aimlessly through a drug store, neither of them wearing a mask. I cringed before realizing that life didn’t always used to be this way. I fantasized, as I often have since the start of quarantine, about when times were normal.

Most of the time, the word “normal” has a neutral, if not negative connotation. Normal is — by definition — not bad but not necessarily something to strive for. Normal is a welcome adjective, but motivational speakers don’t make their living off of taglines like “five easy steps to land a normal job, find normal love and live an all-around normal life.” During normal times, it is easy to feel entitled to an existence that is more than just normal. In times of crisis, such as this one, normal is no longer an entitlement. Normal is now wrongfully fetishized as a dreamlike destination when, in reality, the word normal reflects an unexamined apathy that is at least partially responsible for the exacerbation of the current crisis.

Whether it’s taking in-person classes, being social without distancing or walking — like Jim and Pam — through a drug store without fear of infection, fundamental elements of our normal lives have been taken by COVID-19. The coronavirus has served as a stark reminder that even the most basic aspects of everyday life are privileges that can be lost in times of crisis. We wish life would go back to normal. Yet, as the days go by, our immediate return becomes less and less likely, and we condition ourselves to accept this world as a new normal.

Since the beginning of quarantine, the word "normal” itself has taken on a positive connotation. The positivity of normal is equal in magnitude to the negativity of the times. Amid the unpredictability of an unprecedented crisis, there is comfort in the predictable past. Stripped of previously unconscious privileges, normal life is romanticized. But what really is normal, and does it deserve all of the praise it has recently received?

I think back to when life was truly normal, and I struggle to put my finger on any particular time span. Labeling pre-coronavirus life as normal oversimplifies and devalues a human experience that I know at the time felt far more complex. The existence of normal itself requires a level of privilege that allows for some kind of detachment or lack of attention. For the present to be normal, it has to be unexamined.

To illustrate, when I first met the people who are now my closest friends, for the most part, I found them to be normal. At first glance, they were simply the collection of a name, a face, a major and a hometown. As friendships develop, human complexity becomes undeniable. They are artists, musicians, filmmakers and silent romantics. In describing them, normal is no longer a word that comes to mind. The only normal person is a stranger, and the only normal time is an unexamined one.

Yes, life was more normal when the word “mask” was most mainstream around Halloween and when news headlines didn’t read like a sci-fi script. It is important to understand, however, that normal can only truly exist in comparison. When we wish for normal, what we are really wishing for, is better. We can always strive for better, and we should, but when we strive for normal, we risk complacency.

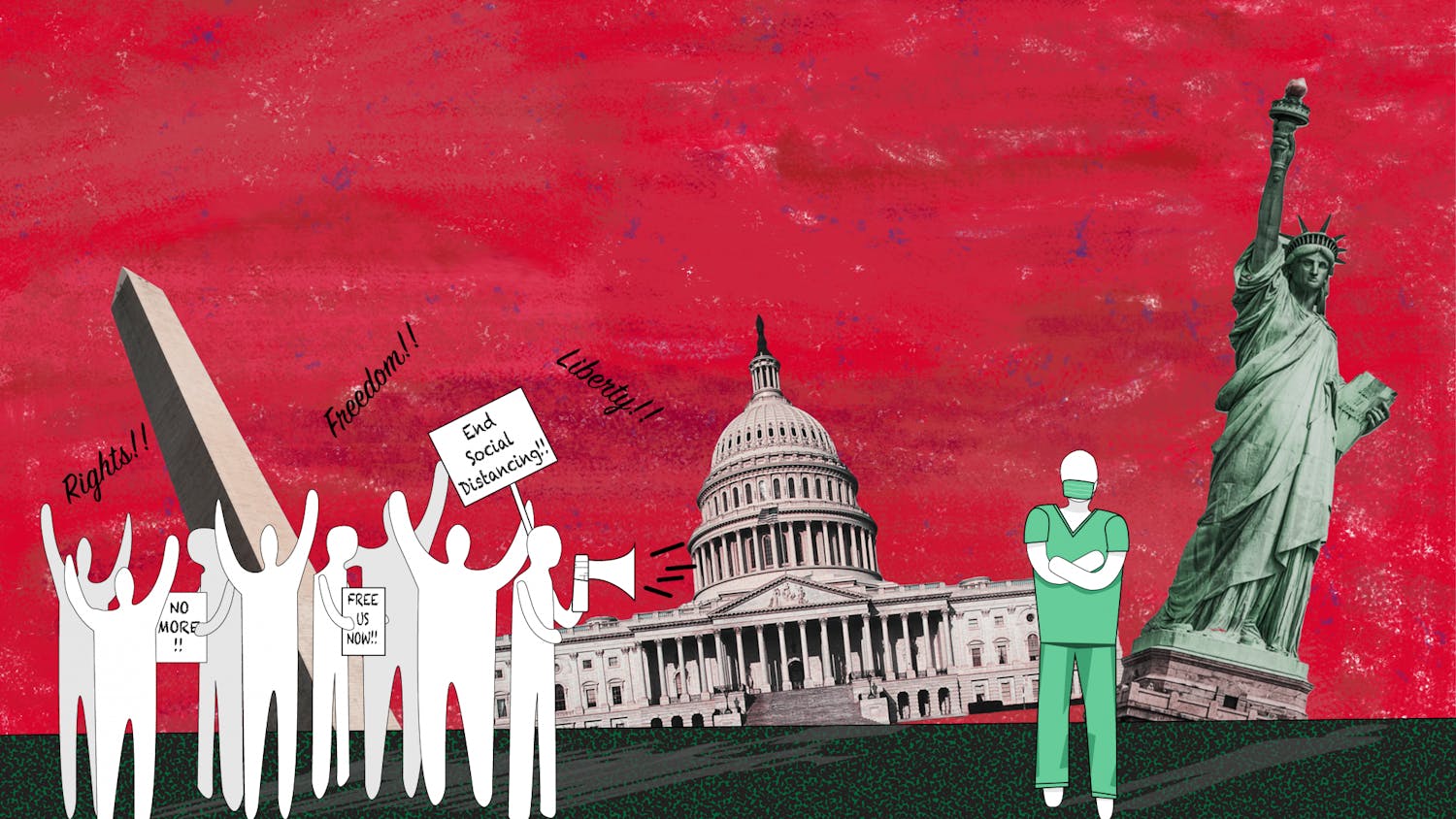

Normal life should not be the goal, as some key characteristics of so-called normal life have exacerbated the current crisis. Indeed, before the coronavirus, it was commonplace to share drinks at a party, shake hands with strangers and go into work even if you were feeling sick. Certainly, the coronavirus spread more quickly because of some of these normalized social practices. More importantly, however, long before the onset of the coronavirus, the spread of misinformation was normalized in the United States. This problem has persisted during the current crisis. Before the coronavirus, we didn’t know which source to trust, becoming frustrated and eventually jaded. Now, this aspect of “the old normal” and “the new normal” costs countless lives on a daily basis. If this is normal, then normal cannot be the goal.

These are unprecedented, tragic and even hopeless times. Nonetheless, we cannot fantasize about returning to normal because normal itself is the product of apathy, not progress.