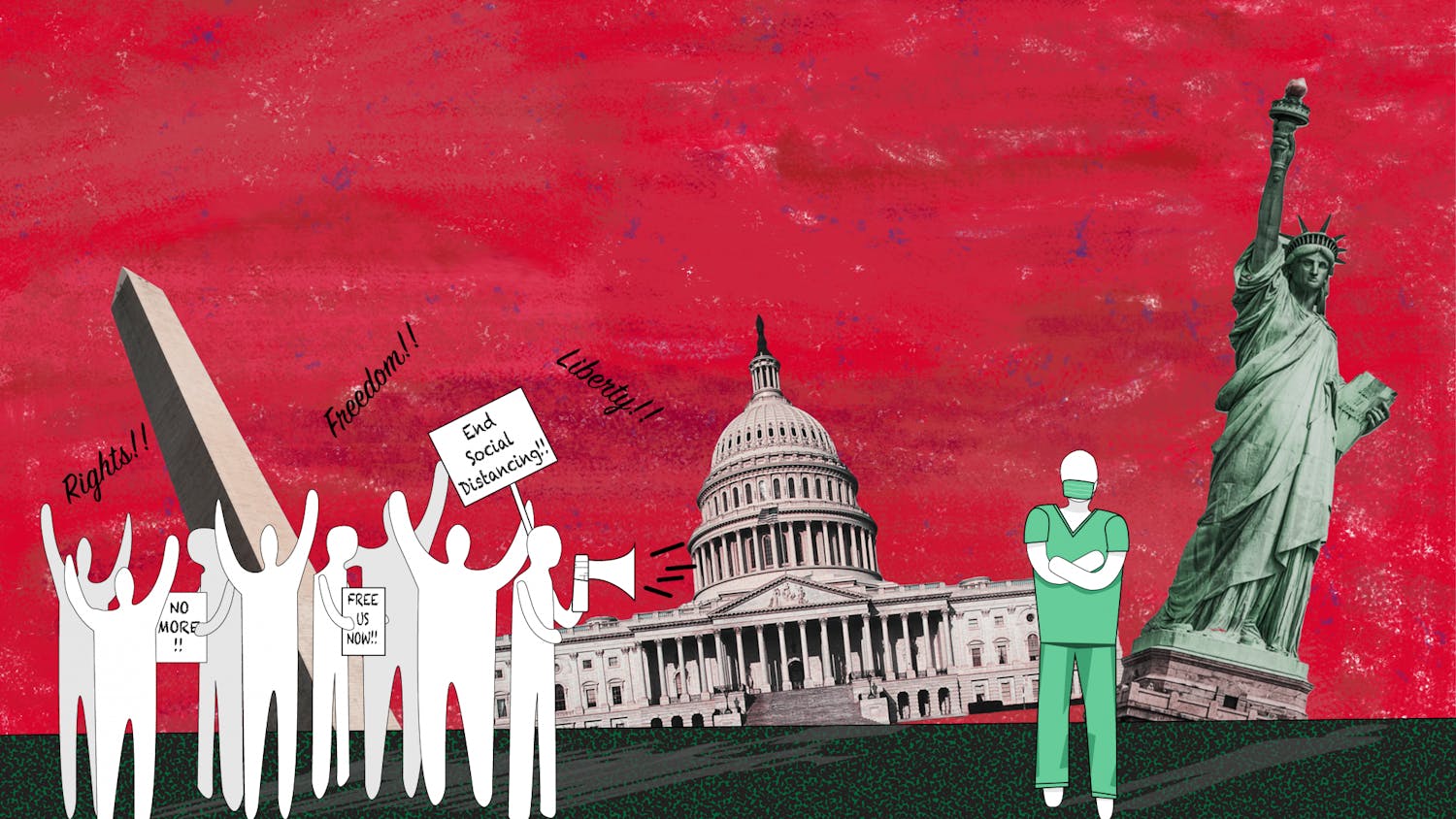

The global COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement continue to rage on throughout the country. The government’s reactions to both have unsurprisingly and consistently failed to protect its marginalized constituents. The U.S. is reaching record-breaking rates of infections and deaths as the failures of the government’s public health measures, or lack thereof, become apparent. Alongside this health tragedy, anti-racist protestors are facing violence and imprisonment at the hands of armed government forces.

Many Americans have focused their energy toward the general election in 2020 as the sole solution for these structural inequalities, namely racist enforcement and scarce health access. The underlying logic is: by defeating Trump, regardless of who the Democratic candidate is, they can create a White House that listens to its people and has the basic common sense to take the advice of experts in all fields.

But simply voting cannot change the unequal order that the United States is built on — it instead centralizes and gives power to that same order. Rather, we require vast structural change.

Relying on voting alone defends the sources of these inequalities rather than aiming to take them down. It is true that certain candidates in various bureaucratic positions could help improve American lives — such as through increased access to healthcare and more open immigration policies. But, as it stands, the change that voting can bring about on its own is not enough. The American political system does not allow space for solutions outside the realm of precedence and broad moderacy. Just this week, the Senate voted 23 to 77 against the second attempt of a progressive amendment that would have put 10 percent of the annual defense policy bill — $74 billion of a whopping $740.5 billion budget — toward education, health care and poverty measures for the most disadvantaged people in the U.S. In times of intensified crisis that have called for broader, sweeping solutions, those in elected positions have refused to place the people over traditional, capitalist agendas.

What to do, then, outside of the sphere of focusing on electoralism as our savior? How can we make material gains that may not be realized within bureaucracy?

Rather than focusing on voting alone, the civic-minded must emphasize other forms of solidarity with marginalized groups. Mutual aid and community work are two examples — remembering that the goal is not a symbolic political victory, but true change. Voting cannot be the sole point where activism ends or begins, as it risks removing focus from the greater mission: a truly liberated people.

And in order to do so, we need to reframe how we think about our relationship with legal and legislative systems; we need to realize that they should exist to serve us, the people.

Accordingly, we should organize to create communities that depend on each other; where people do not have to rely on elections alone to get what they need. Those interested in doing good should manifest the politics of compassion and interconnectedness, figuring out what support their specific community needs. Baltimore-based researcher and organizer Bilphena Yahwon speaks about how definitions of safety often do not include heavy governance or policing, but what people can provide for each other: freedom from harm, compassion, existence without fear. Sometimes, electoralism alone cannot provide or account for these things. Every individual has unique trauma within their lives that the traditional systems cannot account for, but people can. Many contemporary activists offer broad advice on how to account for these diverse experiences. Project NIA, which works to end the incarceration of children and young adults, encourages us to learn how to resolve conflict within our communities, create networks of support that can prevent people from turning to harm and participate in mutual aid, or ”cooperation for the sake of the common good:” a moral commitment and defiance towards normal politics, whether that be through support programs, bail funds, court support, ride systems, rapid responses or other forms of direct help. It is helping those who do not wish to be helped by the state for their own reasons — it is intimate harm reduction in the way that voting is not.

For many, casting a vote is the way in which they make material change. It is their civic duty and how they choose to do good in their communities, especially in local elections. But the important takeaway is that there is always more we can do. We can question why we act and why we are limited in the ways that we are. We can work in ways that bureaucracy deems unviable, understanding that we all want a better world. It is a slow, steady process. But I believe that we can get there.