There is a small portrait of William Shakespeare stuck to my computer, mustachioed and smiling under the sunglasses drawn onto his face. “Today is the day,” I tell Shakespeare every morning when I sit down at my desk. “Today is the day I make you proud!”

Riding this wave of noble artistic purpose, I pull open one of the unfinished plays in my works-in-progress folder. I stare blankly at it. I write exactly three words, and before I can congratulate myself for finishing a sentence, I find myself on Twitter.

“Friendly reminder that Shakespeare wrote ‘King Lear’ while he was in quarantine,” someone has tweeted. I think about my abandoned script, and I turn back to my portrait of Shakespeare. “Are you mocking me, William?” I ask.

Though few feel victimized by the Bard of Avon himself, I am far from the only person struggling to create in quarantine. Writers, artists and creators of all kinds are caught between the expectation of unprecedented free time and the reality of a world in crisis.

In theory, isolation limits external distractions, affording us more time to pursue our interests. In practice, however, isolation is not an idyllic stretch of empty hours; it’s a jarring shift in the rhythms of our lives. Many of us are suddenly juggling the demands of home life, dealing with newfound anxiety and adjusting to monotonous routines. Productivity does not necessarily flow freely in such strained times.

Gus Guszkowski ’22, an avid writer, said that they struggle to pursue familiar creative outlets during quarantine.

“I’m feeling so burnt out by the effort of maintaining long-distance connections that I can’t keep up with my own projects,” Guszkowski said. “I just don’t have the energy left.”

For those who take pride in the act of making things, be it words, art or music, a sudden decline in creative energy can be disheartening. Unable to meet the standards to which we normally hold ourselves, we may be subject to intense internal pressure and feelings of inadequacy. Because I haven’t produced anything rivaling “King Lear,” have I squandered the past two months? Should I be doing better?

Soren Tyler ’23 finds peace by refusing to see the end of quarantine as a creative deadline.

“You don’t have to spend isolation painting the next ‘Mona Lisa’ for it to be a good use of your time,” Tyler said. “The creative things I do don’t have time limits. They’re things I intend to be doing for years.”

By allowing herself to move at a freer, sometimes slower pace, Tyler can more easily forgive creative guilt and find relief in her art. “I can take comfort in the fact that I’ll always have more time to do the things I find enjoyable,” she said.

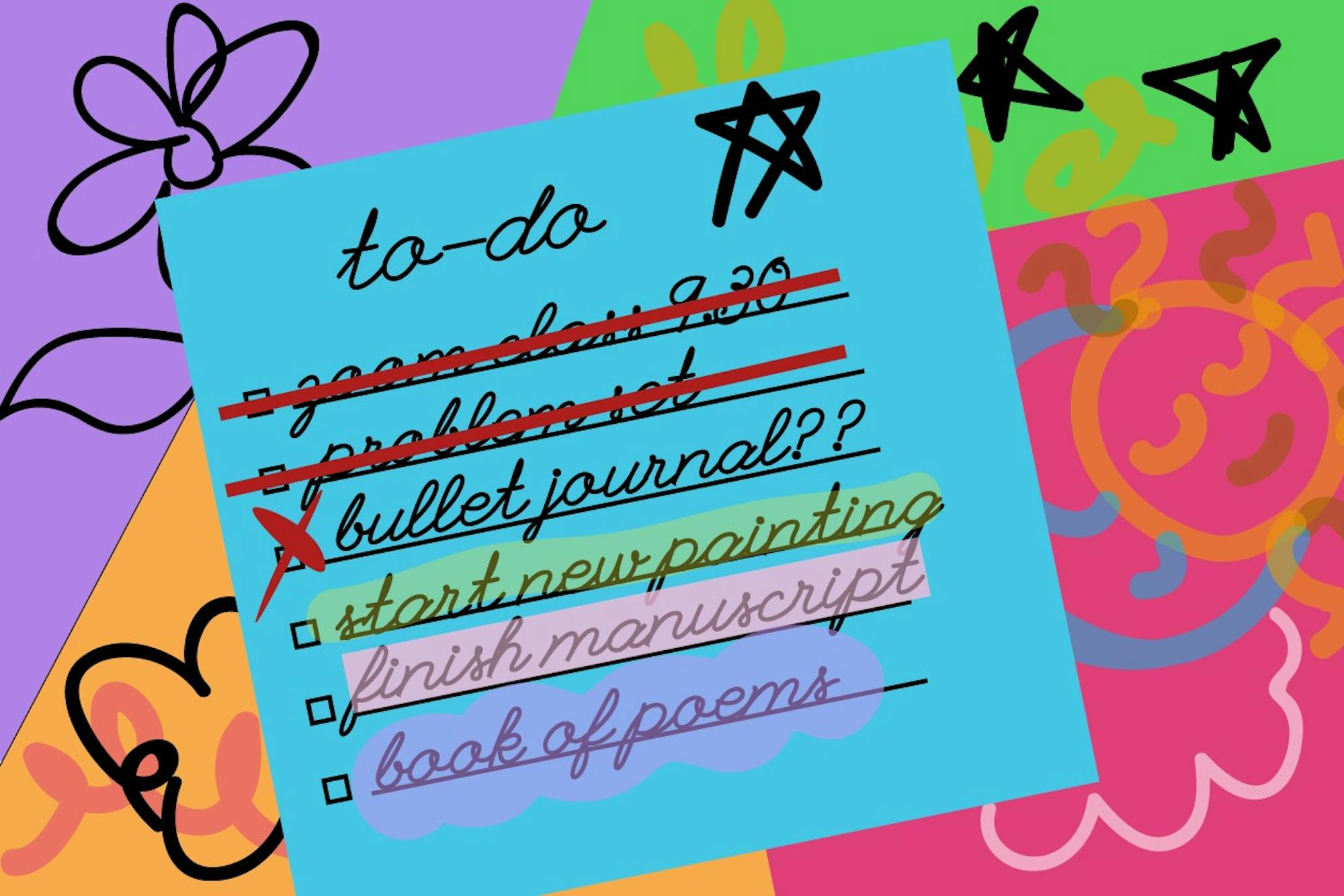

Julia King ’23 echoed Tyler’s sentiment. King is currently working on her second manuscript. While her first manuscript was based on a detailed outline and written on a strict schedule, King is allowing her second novel to take shape on its own.

“I’m writing based on my own pacing and motivation,” King said. “I’ve changed gears, and writing has been my form of leisure time.”

Freed from her usual notions of the writing process, King’s work has taken on unexpected creative dimensions.

“I wrote a twist in [my novel] that surprised me. The tone of the book has changed since that point,” King said. “But I like what I’ve arrived at.” In the next round of edits, she plans to expand on the more spontaneously written chapters, steering the novel in a new thematic direction.

For both Tyler and King, art happens most easily when they take solace in creativity, rather than working for the sake of working. Guszkowski and I have had similar experiences while creating in quarantine.

Though Guszkowski is taking on fewer projects this term, they find comfort in channeling all of their creative energy into a “Dungeons & Dragons” campaign. For this project, Guszkowski is drawing inspiration from their class GRK 30, “The End of the World: Jewish and Christian Apocalyptic Literature in the Hellenistic Era.”

Like Guszkowski, I am focusing on the creative projects that make me most happy. I might not have the energy to write a crushing five-act drama, but embroidering flowers reminds me why I like to create.

Laura Beth White, a certified wellness coach and program director at the Student Wellness Center, emphasized the importance of reflecting on our own needs.

“Mindfulness is slowing down and stopping, taking time to reflect when things are getting hard. When we have this layer of guilt for not doing what we ‘should’ be doing, I think the most helpful thing is to recognize it with gentle compassion and acceptance instead of self-critique,” White said.

For many of us, producing a magnum opus in quarantine is just not possible. And that’s OK. Listen to yourself, and create when it comforts you to do so. If it makes you feel any better, Shakespeare probably took it slow too. Though we like to think that he sat down and banged out a sparkling “King Lear” in a single quarantine period around 1606, three different versions of the script were published between 1608 and 1623. Scholars suggest that Shakespeare revised “King Lear” between publishings to accommodate his changing vision of the play.

Our art changes as we do, so it’s natural that the things we create look different in the wake of this extraordinary paradigm shift. When the spirit of creativity eludes us, we survive by forgiving its absence and moving on as we are able. Who knows? The little things we make in isolation may just be the start of something great.