Sometimes, it’s a question: “How do you know so many people?”

Other times, it’s an exclamation: “You know everyone!”

Whatever the exact wording is, it’s something I’ve heard again and again. I’ll be with a friend, perhaps passing through the library or getting food, and I’ll bump into some people I know. I’ll say “hi,” and afterward, the friend I’m with will inevitably make some kind of comment.

I usually laugh it off and point out that I haven’t met the vast majority of people on campus, but if I’m being honest, those kinds of comments bother me more than I’d like to admit. They make me feel like I should be happy, maybe even proud, of putting myself out there and “winning” some kind of popularity contest. It’s as if the number of people I know should be directly proportional to the quality of my social life and my self-esteem.

The truth is, a lot of the time I feel pretty damn lonely.

On a good day, I can walk across campus with my head held high and feel confident about my place in the Dartmouth community. But on a not-so-good day — and there are many — I can’t help but wonder what I’m doing wrong. Sometimes, that takes the form of posting a picture on Instagram and obsessively checking how many likes it’s gotten, wondering how others manage to get hundreds of likes before I can even get 10. Sometimes, it means watching my classmates attend exclusive “A-side” parties to which I’ve never gotten an invitation.

Sometimes, it’s as simple as realizing that a lot of people on this campus never have to eat a meal alone; for me, that’s a regular occurrence, sometimes by choice but often not.

Say what you want about popularity and “social capital” and how these things don’t matter in the long run. That doesn’t change the fact that they negatively affect many students’ emotional and mental health, including my own.

Even this term, I’m not immune to it all. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel jealous when I see people on social media having regular Zoom hangouts with their many friends. To pull that off, you need a certain kind of friend group and a certain amount of free time, and I have neither.

I know I shouldn’t, but sometimes I do think about what I’m “doing wrong” and what I could have done differently to feel a little better about my social life. I mean, I’ve never felt super popular at Dartmouth, but there have definitely been terms where I felt a bit more socially relevant.

The more I think about it, the more I think things might have gone differently had I opted for a more “mainstream” Dartmouth experience.

Up until junior fall, I was still trying to convince myself that I wanted to be a biology major, and even though I never saw myself as pre-med, I was still taking most of the classes along that track. I was miserable — I can’t emphasize that enough — but there was something nice about being able to study in groups and find a sense of camaraderie among my classmates.

Once I finally let myself abandon biology and turn to a Romance languages major, classes got a lot lonelier. I met a lot of great friends in my language classes, make no mistake, but most of them were in it for the short-run: to complete the language requirement, go on a study abroad or, at best, minor in a language and major in something else. People don’t usually take more language classes than they have to, so as the terms went on, there were fewer and fewer upperclassmen in my classes. Even now, as I complete my “culminating experience” in my major, I’m the only senior in the entire class taking it for Italian credit.

I think another factor was my group involvements. I was rejected from a lot of groups freshman year — including Dimensions, an a cappella group and the Hill Winds Society — that I had hoped would be ways to connect with upperclassmen and find my “family” on campus. I eventually found other involvements that I felt passionate about, like The Dartmouth and the tour guide program, but there’s no denying that those groups didn’t offer as strong a “community” as what I was looking for.

All of that said, my freshman experience wasn’t particularly abnormal, and my social life freshman year was just fine — I even earned a reputation as one of the “FaceTime-y” freshmen, an identity I embraced as a sort of badge of honor. Once sophomore fall came, however, everything changed: I was eager to rush a fraternity and enjoy the social benefits that came with a Greek affiliation.

Going through rush is an incredibly mainstream Dartmouth experience; what’s a little less mainstream, and what I didn’t expect, was joining a house that would pretty much immediately be hit with a three-term suspension. What was supposed to be a term of meeting new people and celebrating with my friends in other houses became a year of feeling out of place whenever I went out. There was a sort of unspoken rule that once you rushed a fraternity, you stopped hopping from house to house since you now had a social space of your own — that didn’t make me feel any better.

Once our suspension was lifted, I naively grew optimistic again, thinking that I’d finally get to make up for lost time. I was so optimistic that I even ran for social chair, since I thought that being “FaceTime-y” combined with a genuine desire to branch out and make new friends was a perfect recipe for success.

Spoiler alert: of the three positions I’ve had in my house, being social chair was by far the worst. There I was, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, assuming that other houses’ social chairs felt the same way I did about wanting to meet new people and have fun. I was in for a harsh awakening when I quickly learned that other houses had already established how they wanted to plan their social calendars, and since we were late to the game, they wouldn’t even give us a chance. If I was lucky, a social chair would say that their calendar was already full, since at least in that case I wouldn’t get my hopes up. If I wasn’t so lucky, then they’d get back to me saying they’d love to plan something, only to either double-book or just stop replying to me altogether.

I’m painfully aware of how silly this all sounds, getting so worked up over something like Greek life “politics.” But I was a gentler person back then, without as hard of a shell, and I really was heartbroken that something I was so excited about, and that I worked so hard on, was ruined by forces outside of my control. I had previously considered myself a pretty social person, and I thought I knew a lot of people — but, in the most literal way possible, Dartmouth let me know that just “knowing” people wasn’t nearly enough.

If I sound bitter, or hurt, or even angry, it’s because I am. Or, at least, I was. As the years have passed, a lot of the people I “know” have become people I knew. Past tense. People I used to wave to when we passed each other, at some point, stopped waving back, or maybe they seemed confused why I was still going out of my way to talk to them, and eventually I got the hint.

I fundamentally like people — I always have, and that hasn’t changed. As far as popularity goes, however, I’ve had to learn the hard way that simply knowing a lot of people doesn’t directly translate into happiness, social or otherwise. The quality of those friendships matters more than the quantity, and quite frankly, I’ve invested too much time in the low-quality ones hoping that they’d make me feel better about myself.

They didn’t.

It seems wrong to wrap this up without acknowledging that I do have a lot of really great friends, and I wouldn’t trade them for all the party invites and Instagram likes in the world. This piece isn’t about them; it’s about a system and social hierarchy that I couldn’t have “won” no matter how hard I tried.

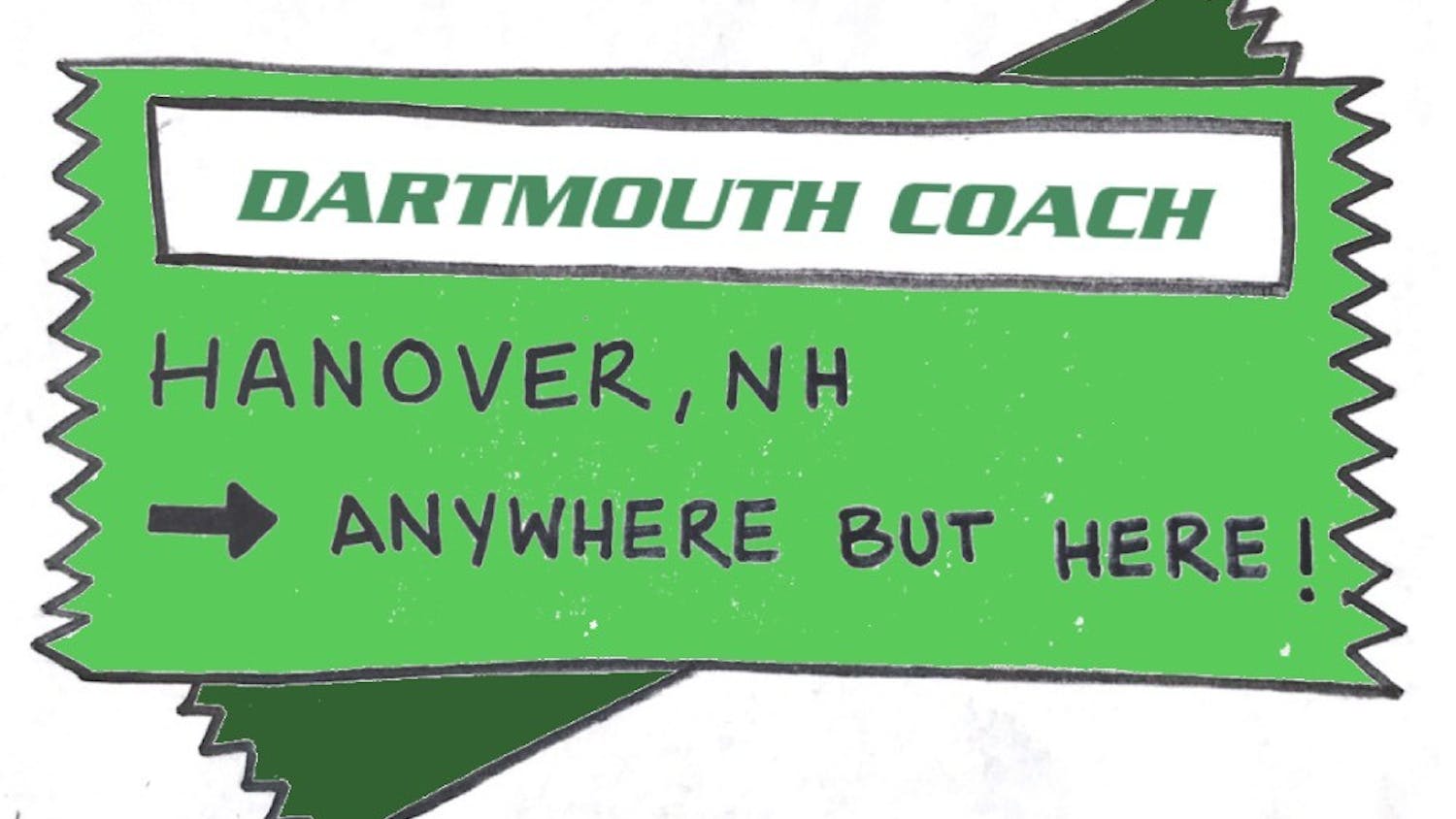

When I graduate, I’ll bring with me the strong friendships I’ve fostered at Dartmouth, and undoubtedly I’ll make many more in the working world. Worrying about popularity, on the other hand, is something I’ll be happy to leave behind.