Last week, my dad and I started watching “Baseball,” Ken Burns’ great documentary series telling the long and rich story of America’s national pastime.

It’s not the first time either of us have watched the series. I binge-watched it on Amazon Prime a few years ago, and my dad watched it when it first aired on PBS in 1994.

Those of you who are avid baseball fans know that in August 1994, Major League Baseball entered its eighth-ever work stoppage, a strike that would last for 232 days until then-U.S. District Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor issued an injunction stopping the MLB owners from using replacement players.

If that’s not a reason to be put on the Supreme Court, I don’t know what is.

Watching Burns’ “Baseball” helped many fans at the time get through one of baseball’s darkest hours — a strike driven by greed in a battle between millionaires and billionaires that left fans angry and cynical about the sport they loved. Attendance and television ratings dropped when the 1995 season finally got started, and baseball was in crisis.

But the sport would be saved just three years later, when the home run race between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa riveted the country, drove news cycles and filled ballparks. Thanks, steroids.

In the midst of the global pandemic, baseball, like all other sports, has gone dark, and Ken Burns announced that his “Baseball” is streaming for free. That’s good news for baseball history buffs like my dad and me, but I doubt that it will be enough to fill the void left by the delay to the start of the baseball season, which was supposed to open this past week.

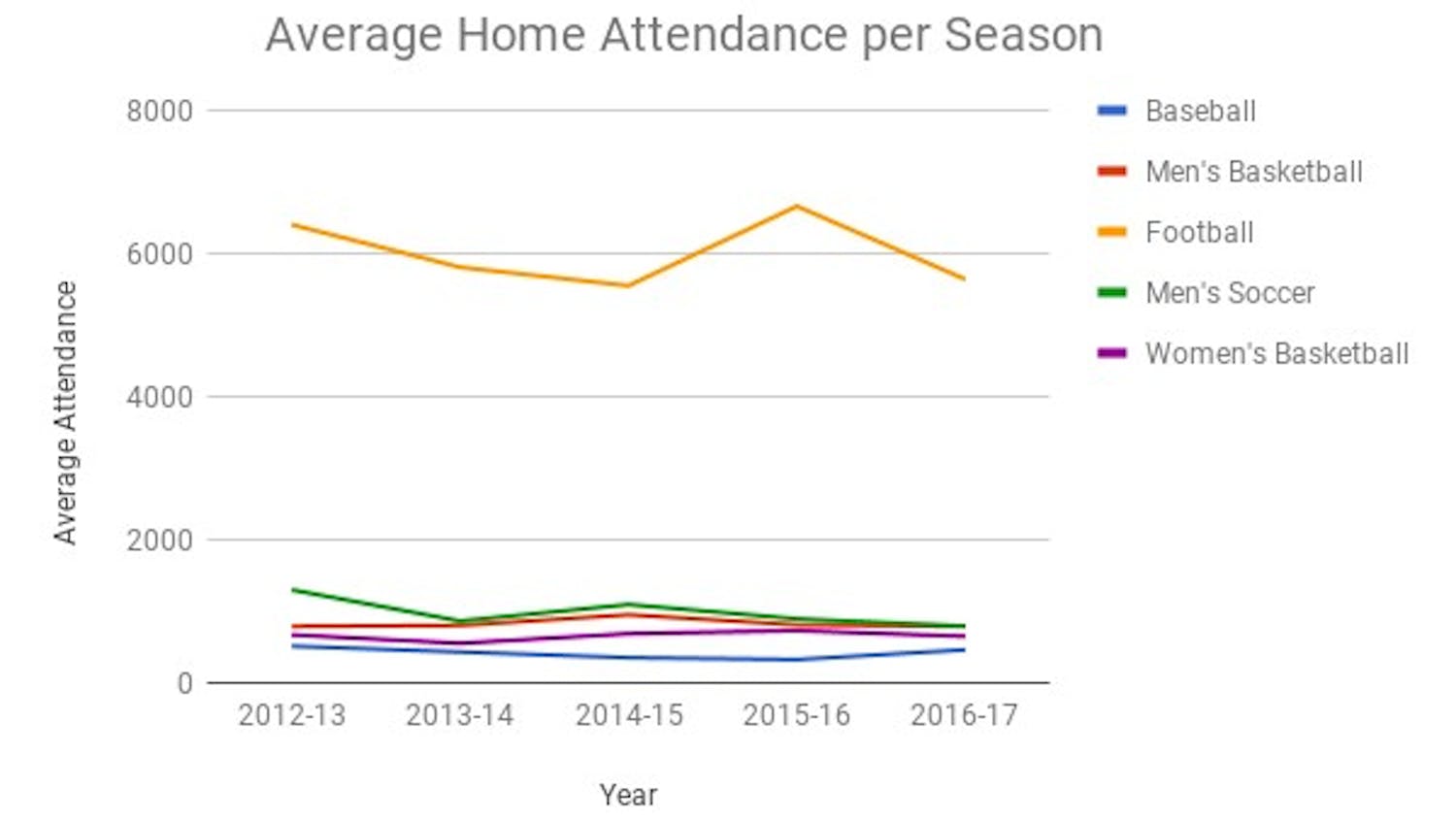

While I certainly hope that baseball will return sooner than it took to end the strike of 1994-95, I have a bad feeling that the sport will be in big trouble when play eventually resumes. With attendance dropping over the last few seasons and the baseball world consumed by a major cheating scandal, it’s enough to make me wonder whether the sport will be able to recover after the public has experienced its first spring in a long time with no baseball.

It seems to me that every time baseball has been in trouble over the years, it’s been the home run that has saved the game. If it hadn’t been for McGwire, Sosa and then Barry Bonds, people might have stopped watching. And baseball was able to recover from the serious credibility shock incurred by the 1919 Black Sox scandal in large part because right after that, Babe Ruth rocketed to fame by becoming baseball’s greatest power hitter ever.

It’s true that for many people, home runs are the most, and perhaps only, exciting part of the game. I’ll admit that I’ve been to some baseball games that were pretty lousy, only to be saved by someone hitting a home run late in the game.

From the perspective of the MLB owners, home runs are what sell tickets and drive the profit machine. And if there’s no excitement in the game, how else could you justify those big TV contracts worth only slightly less than the recent federal stimulus package?

That might be the reason why over the past few years, baseball has taken a dramatic shift toward emphasizing the home run over all else. Advanced analytics and techniques such as focusing on the “launch angle” of the swing have caused the last three seasons to go down in the record books as three of the four highest in total home runs in MLB history. Of course, it’s no coincidence that the last three seasons were also the three highest ever in terms of strikeouts. And the league batting average of .248 in 2018 was the lowest since 1972.

I’ve always considered myself a skeptic of the long ball, going all the way back to my playing days. I had a pretty high slugging percentage on my T-ball team, but I really got thrown off my game once we transitioned to live pitch. Things went downhill from there, and by the time I called it a career in eighth grade, I considered myself more of a defensive specialist.

Call me old-fashioned, but I think other aspects of the game — the strategy session on the mound, the game-tying double into the gap, the 6-4-3 double play — are a lot more interesting than home runs.

I’ve also always been fascinated by the concept of stealing signs. It certainly makes it easier to hit home runs when you know what kind of pitch is coming. It also makes it easier to know what kind of pitch is coming when you use live video cameras, as the Astros discovered over the last few years.

You know, I remember thinking a few months ago that the fallout from the Astros cheating scandal would be the biggest sports story of 2020. The MLB took a pretty big hit in terms of its credibility with the fans — after all, there are plenty of other fine options in professional sports if you want to watch an event in which the outcome is rigged.

If that isn’t bad enough, I think fans have wised up since the players began to make sacrifices upon the altar of the launch angle gods. Attendance has dropped significantly in the last two seasons, plummeting to the lowest it’s been since 2003.

With the average game length continuing to increase despite rule changes designed to bring about the opposite, I have a bad feeling that this trend will continue. If there’s anything we’ve learned over the past month, it’s that pandemics force society to reckon with traditions — perhaps even one so ingrained in our culture as the national pastime.

Baseball is in trouble once again, and I doubt the home run will save it this time. As the great Yogi Berra once said, “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

I’m afraid that doesn’t bode well for baseball.