After trying to fall asleep for hours, plagued by the worried insomnia that living through a pandemic seems to cause, I rolled over to grab my phone and open the podcasts app — a last-ditch effort to soothe myself to sleep. I tried to find something mindless, searching for a calming voice talking about anything that could help me relax. But every single recent podcast was about the coronavirus. None of these would help me sleep.

Last term, I wrote an article for Mirror about our civic responsibility to stay updated on the news. Today, with hundreds of thousands of lives on the line, that civic responsibility seems to shift to a moral one. We have to stay updated on what is going on so that we can make safe and informed decisions. But how do we balance that responsibility with our own mental health?

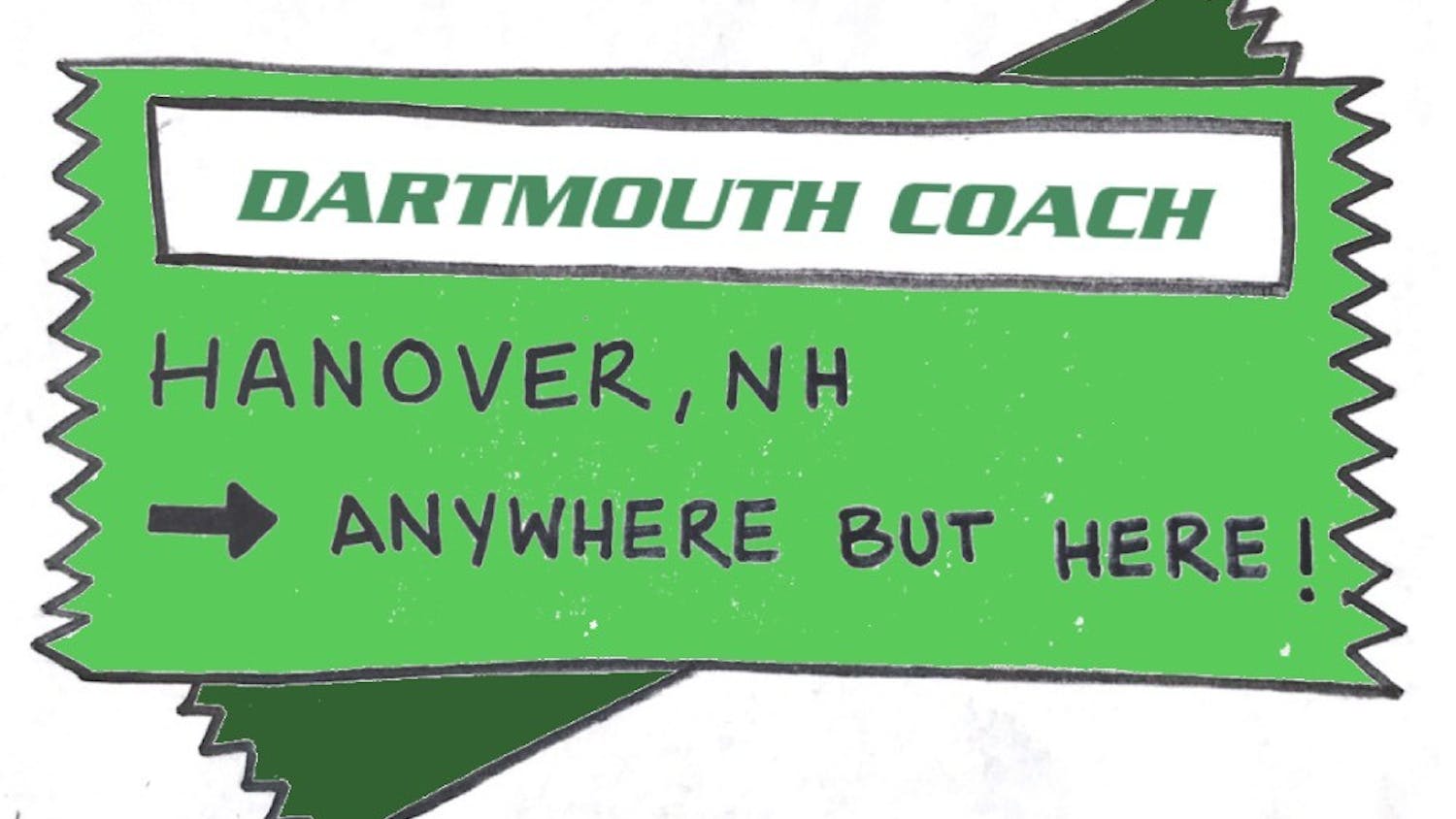

Dartmouth students have scattered to all corners of the Earth, facing an unprecedented situation and grappling with its mental health effects. On top of dealing with their day-to-day lives, students also have to figure out how they want to engage with the news. Inundated with statistics and guidelines that change every day, how do you know when you’re reading too much? When there’s nothing to do but scroll, how do you stop?

The World Health Organization suggests minimizing news intake that makes you feel anxious or distressed, and checking the news on a schedule, once or twice per day. The WHO also emphasizes the importance of getting news from trusted sources and not listening to rumors or misinformation.

Despite that advice, about 51 percent of United States adults claim to follow the news very closely, with another 38 percent following it fairly closely, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center. According to Vox, news coverage of the coronavirus made up 10 percent of total media in early March. Yesterday’s New York Times did not feature a single front page story on anything other than COVID-19. Readers are following this lead — as of March 15, page views on coronavirus-related articles were up 50 percent from the previous week.

In their responses to the crisis, Dartmouth students represent both sides of the coin: some have increased their news consumption, and others have decreased it.

Rachel Gambee ’21 started off as an avid news consumer. She said that she primarily gets her news from podcasts, listening to them for about three hours a day.

“[The coronavirus] definitely caused me to double down [on my news consumption] because I now have the time, unlike in a normal Dartmouth term,” Gambee said. “This does give you the sense that you want the freshest news. Whereas in the past I might listen to a day-old podcast or read a day-old article, now I only want the freshest stuff.”

Nina Nesselbush ’23, on the other hand, has decreased the amount of news she reads.

“I know it’s really important to be informed, and I definitely am,” Nesselbush said. “But I think there’s a line of doing that too much and obsessing over it, and I’m trying not to do that.”

Jenna Gallagher ’21 echoed Nesselbush, saying that for the sake of her mental health, she has decreased how much news she listens to and tries to focus only on essential headlines. Her internship for the National Women’s Law Center requires her to stay updated, but other than that, she tries not to fall down the “rabbit hole” of media consumption.

“It’s just the same depressing thing all the time, and in the moments when I’m not working, I don’t want to feel suffocated,” Gallagher said. “Whatever I do in my leisure time, I like it to be something that helps me forget what’s going on rather than forces me to remember.”

Overall, Nesselbush said that she has been able to find a decent balance, especially because she doesn’t check her phone until her classes finish for the day, and she doesn’t often get distracted by the news.

Likewise, Gambee finds herself consuming a manageable level of content. Over spring break, she found herself checking the news compulsively, but her new class routine has allowed her to put down her phone.

“I think that some of my friends who do not consume news as rabidly as I do are now are starting to only read headlines and get really freaked out,” Gambee said. “I think because I read news so frequently, I am slightly inured to some of the panicked headlines. Not that I don’t think this is something to be panicked about — I think this is absolutely an unprecedented global tragedy. I think that I am a little bit more skeptical about some of the outlandish predictions.”

Panic is definitely the sign of the times, but Gallagher agreed that fixating on negativity can be a slippery slope.

“You just have to keep tricking yourself that everything is okay and avoid going into that place where everything is a disaster,” Gallagher said. “Because if you get to that place, it’s super hard to get out.”

With news integrated into social media and almost everything we do on our phones, it’s hard to avoid talking about it. Nesselbush said she finds that every conversation seems to start and end with the coronavirus.

“Now, [my friends and I] just communicate by texting articles,” Gambee said. “We don’t even respond to the individual articles; someone will text an article in a group chat and everyone responds with a different article.”

Even though the barrage of headlines can be overwhelming, Gallagher, Gambee and Nesselbush agreed that it’s imperative to check local and federal regulations regarding the coronavirus — and to abide by them.

“Beyond [keeping up with guidelines], I would hope that as a curious and engaged citizen, you are trying to consume enough news that you can make a considered decision about the things that you believe, particularly going into an election year,” Gambee said.

When there are so many facts and statistics to digest, how do you find room in your media diet for other types of news? Opinion pieces can offer valuable insight, although Gambee noted that they often cite day-old statistics, which, in a rapidly evolving situation, can be outdated.

Gallagher also warned of news that she has seen to be inconclusive or fear-mongering, particularly on cable television. She said that people need to distinguish between credible updates and opinions or conjectures, and also be mindful about how they react.

“For the most part, I think people should limit their news consumption or limit how much they let it govern their lives, so that it doesn’t interrupt their responsibilities,” Gallagher said. “You don’t want to let the fear rule everything you’re doing. You shouldn’t let the news that you’re hearing stop you from finding some joy every once in a while.”