This article is featured in the 2020 Winter Carnival special issue.

In 2014, Johns Hopkins University made waves when it ceased legacy preferences in its admissions process — reflecting a growing nationwide attitude of resistance toward the practice.

But at Dartmouth, as well as other highly selective schools, legacy status has had, and continues to have, a noticeable presence in admissions.

In contrast to the stark change in Johns Hopkins legacy admission policies, dean of admissions and financial aid Lee Coffin wrote in an email statement to The Dartmouth that the College has not changed its legacy admission practices over the past decade.

This past year, roughly 12 percent of the incoming Class of 2023 are legacy students. Though Coffin wrote that “[legacy] relationship is considered as one factor among many in our holistic evaluation process,” former dean of admissions and financial aid Maria Laskaris ’84 wrote in a 2011 article in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine that legacy applicants not only receive “at least one additional review in this process,” but also are admitted at a rate “two-and-a-half times greater than the overall rate of admission.”

Laskaris noted in the article that “it’s never easy to turn away the children of Dartmouth alumni.”

Dartmouth is not unique among its peer institutions in legacy admission practices, and many U.S. colleges herald it as a longstanding tradition. A study by Purdue University found out that Dartmouth was the first college to start the practice of legacy preference in 1922, as “part of a much larger nativist response to the growing presence of religious minorities who did not share the nation’s Protestant heritage.”

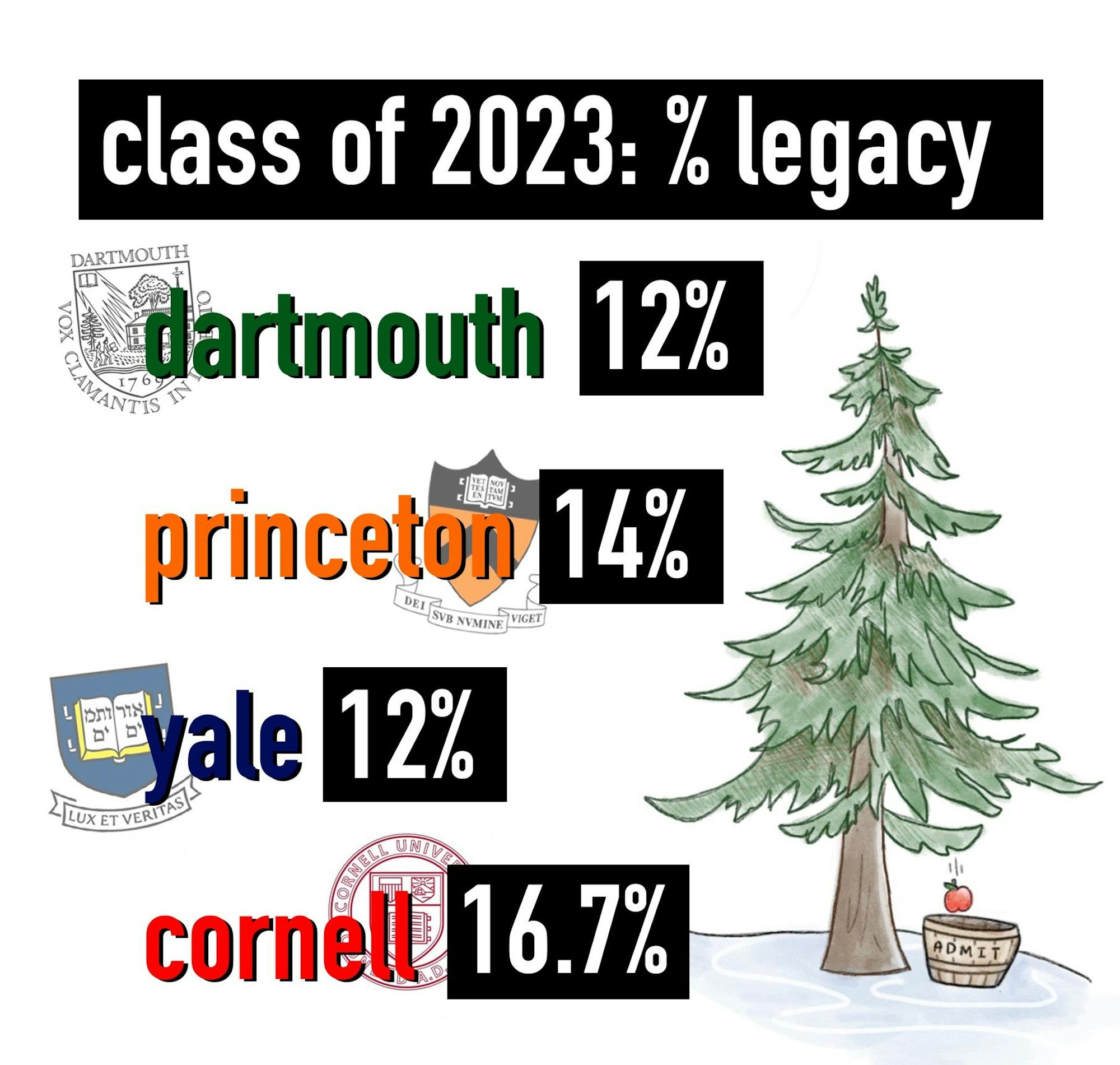

Today, though a number of universities — such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the California Institute of Technology and the University of California Berkeley — either abandoned or never adopted the preference for legacy applicants, a greater number of schools still retain this long-established preference for legacy students. For the enrolled Class of 2023, Dartmouth recorded the lowest percentage of legacy enrollments of the Ivy League, while Cornell University had the highest percentage of legacy students that year with 16.7 percent, followed by Princeton University with 14 percent.

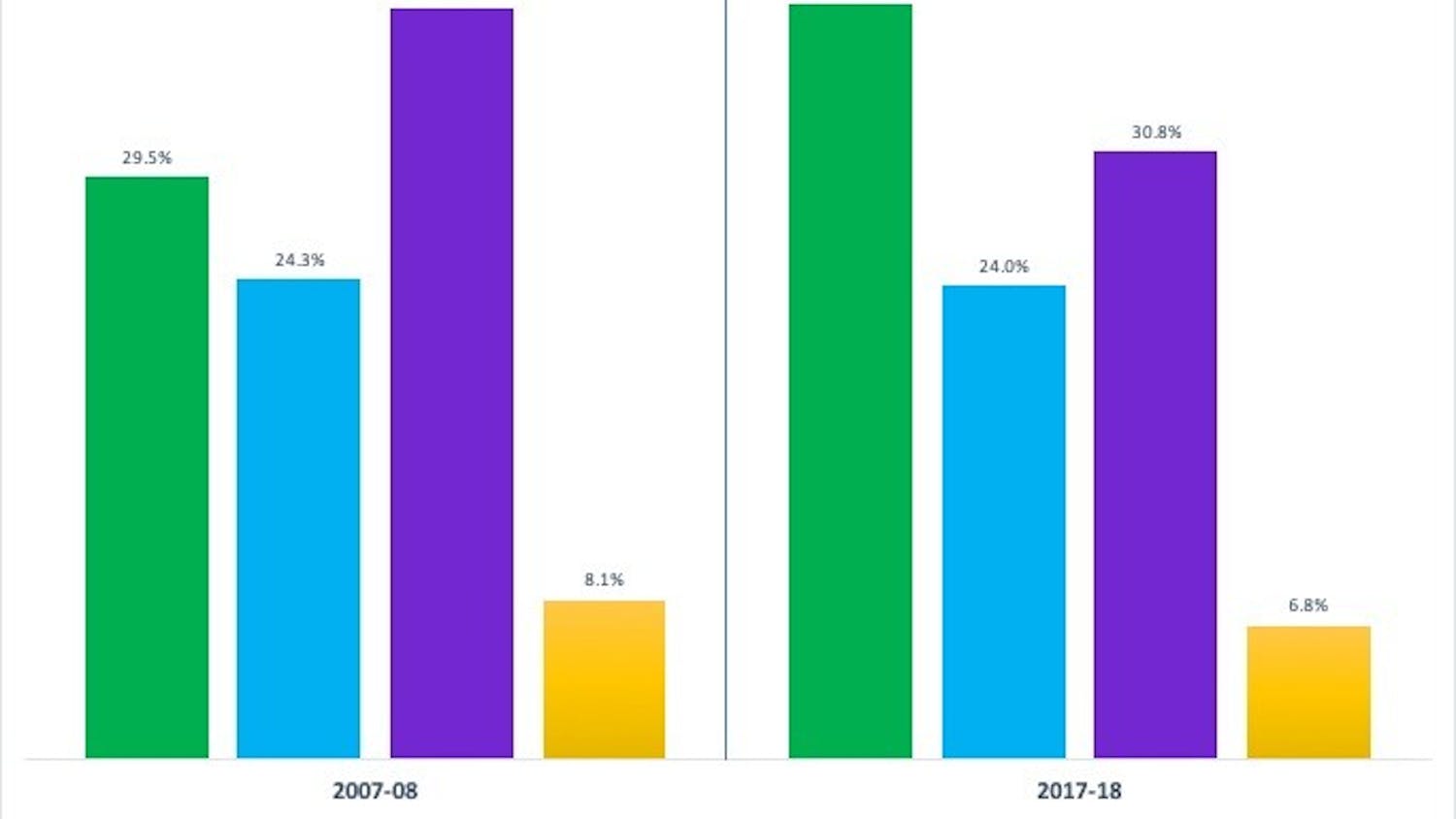

Enrollment data published by Dartmouth’s Office of Institutional Research document an initial increase in the percentage of legacy student enrollments at the beginning of the millennium, followed by a overall decreasing trend starting in 2014. From 2000 to 2013, the proportion of legacy students grew from around eight percent to 14 percent, with a notable 35-percent jump in the number of legacy students from 2009 to 2010. Starting from 2014, the proportion of enrolled legacy students began to gradually decline, from over 13 percent in 2014 to around 12 percent in 2019.

As Johns Hopkins president Ronald Daniels wrote in a recent article in The Atlantic magazine, “Defenders often argue that legacy preferences are a powerful tool to strengthen multigenerational bonds within a university community.” For institutions like Johns Hopkins, Daniels said these schools rely on a strong network of dedicated alumni for counsel, outreach and support.

Similarly, at Dartmouth, legacy preferences has played a crucial role in fostering a sense of community for alumni and students across generations.

“Dartmouth alumni are very passionate about their alma mater and that generational connection to the College is an important element of the Dartmouth community,” Coffin wrote.

Nevertheless, from the perspective of current legacy students at Dartmouth, their legacy identity does not necessarily boost their sense of community on campus. For example, Talia Pikounis ’22, whose mother, uncle and aunt went to Dartmouth, said she values her family connection to the school, in the sense that they share many common topics regarding their college experiences. But she said that her actual Dartmouth experience has not depended much on her family’s connection to the school.

“When [my family] visits, they can go to their old dorms,” Pikounis said. “I led a First-Year Trip and my uncle led a First-Year Trip, so we can talk about how much it changed. But I don’t think it means I have more of a community here than anybody else. As soon as you get to Dartmouth, it really doesn’t matter whether you are a legacy or not. Everyone finds a community here, and people don’t look at you as ‘Oh,you are a legacy’ versus you are not.”

Many colleges believe that legacy preferences drive alumni donations. A Harvard University committee that sought to examine the school’s admissions practices concluded that ending legacy preferences would “diminish this vital sense of engagement and support” from its alumni’s “generous financial support.” Nevertheless, a study that compared legacy admissions and alumni giving across the top 100 national universities found that “the presence of legacy preference does not result in significantly higher alumni giving.” According to the study, the data demonstrates a strong correlation between alumni giving and legacy preferences, but only prior to controlling for wealth. This suggests that the greater alumni giving comes from elite colleges’ ability to “over-select from their own wealthy alumni population.”

Dartmouth vice president of development Andrew Davidson said that his office does not track statistics on legacy donors — for example, whether legacy donors give more or give at a higher rate — and declined to comment further.

Admissions Ambassador program director Margaret Lysy ’99, who is in charge of alumni interviews in the admission process, said that knowledge of an applicant’s legacy status is not passed to any alumni interviewers. To avoid any conflict of interest with alumni interviewers, if alumni volunteers have children applying to Dartmouth a certain year, the Alumni office doesn’t work with them that year.

In an email statement to The Dartmouth, Johns Hopkins vice provost of admissions and financial aid David Phillips wrote that the preference for legacy applicants hinders the inclusiveness of their college community, as the unfair advantage given to legacy applicants precludes the admission of equally or more qualified students from lower socioeconomic statuses without legacy connection.

Phillips wrote that in 2009, Johns Hopkins’ entering class had more legacy students (12.5 percent) than students who qualified for Pell Grants (9 percent). Having eliminated legacy preferences, only 3.5 percent of this year’s freshman class has a legacy connection and 19.1 percent is Pell-eligible.

“Ending the practice of legacy admissions has accelerated our work of recruiting and matriculating students from all walks of life who demonstrate the academic rigor and exceptional talent we expect of all Hopkins students,” Phillips wrote. “[It] is one important step in the process of building a more socio-economically diverse student body.”

Conversely, for many people, the higher admissions rate for legacy students is understandable. For instance, a non-legacy student, Jiayuan Liu ’23, said she believes the higher legacy admissions rate is not necessarily an unfair advantage given to those applicants during the admissions process.

“Graduates of Dartmouth College typically have a higher educational background than people in general, so I guess it is more likely for their children to receive better educational opportunities and achievement compared to students from a middle or lower class family,” Liu said. “Even if our [legacy admissions] rate is higher, it can just be a result of [those applicants] being more qualified.”

Director of admissions Paul Sunde and representatives from the Development Office declined to comment for this story.