The next Democratic debate, on Jan. 14, will likely have only five presidential contenders. There will be the three clear frontrunners — Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren — along with Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, both of whom recently cleared the DNC’s threshold for a debate stage appearance.

That all of the five likely contenders to appear on the next debate stage are white reflects a dissonance between rhetoric and action in the Democratic Party — a party which claims to represent the interests of a diverse nation. The failure of black candidates to gain and maintain serious momentum in the Democratic primary only reinforces what so many black Americans have always known to be true: the perennial problem of racism in American elections.

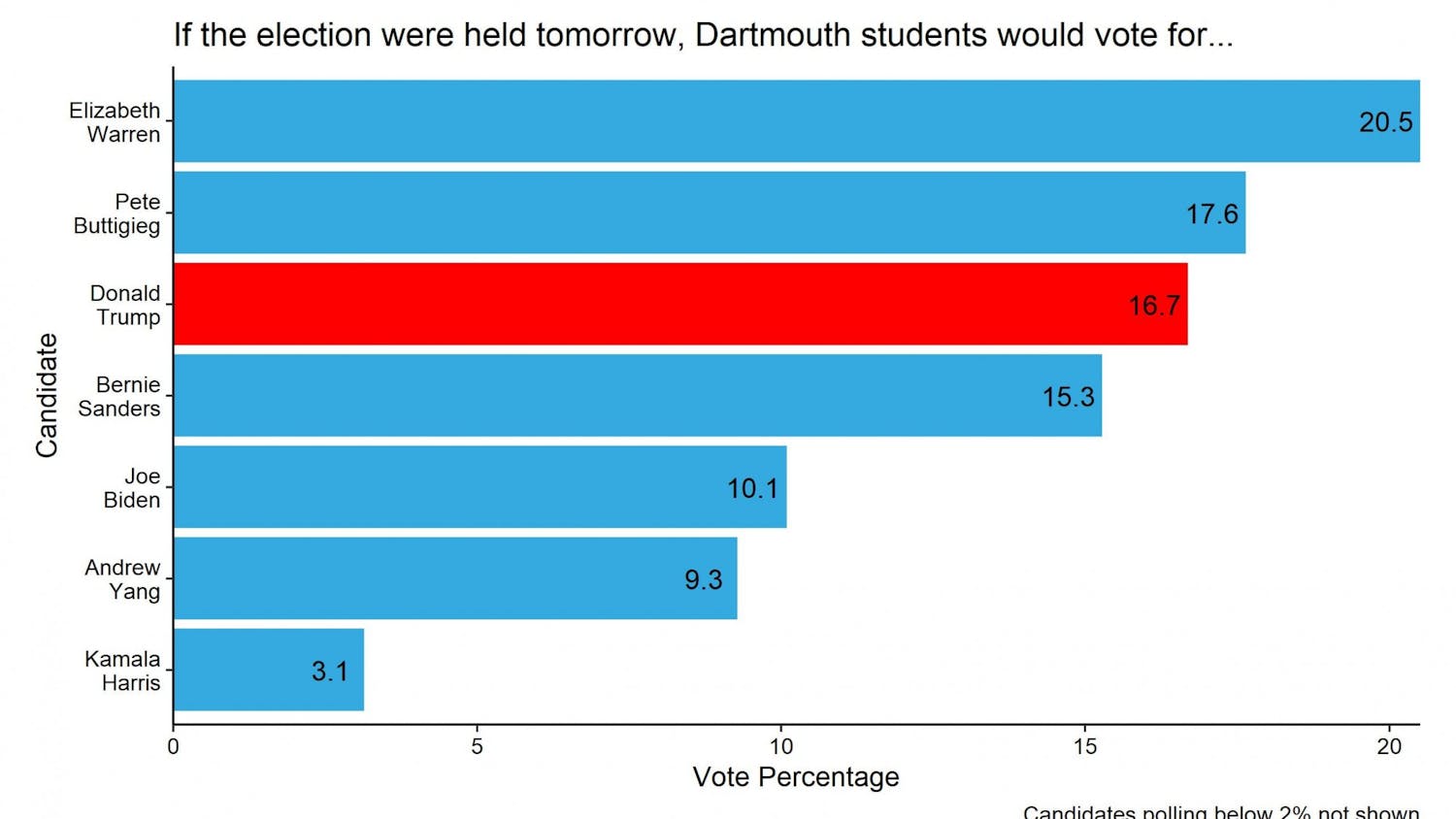

Take the ascendant political star Kamala Harris, who many saw as one of the most viable of the candidates of color as Cory Booker and Julian Castro languished below four percent in national polls. Pundits and analysts were quick to offer conclusions as to why Harris’ campaign, which once enjoyed high enough poll numbers to rival the frontrunners’, lost its momentum and stalled. Harris muddled some of her policy positions, specifically her stance on Medicare for All, and lost supporters to the more robust campaigns of Biden and Warren. Progressives also critiqued her prosecutorial record of fining parents for truancy while she was attorney general of California.

While those were indeed serious roadblocks for her campaign, to ignore the role of racism in Harris’ withdrawal would ignore why those shortcomings dealt so much harm to her campaign and not to others. It is important to ask, as New York Times columnist Charles Blow did in December, why these perceived missteps brought down a campaign with so much promise. “Every campaign has missteps,” Blow wrote. “It is hard to look at this field of candidates and not remember a cascading list of missteps.”

Biden, the current frontrunner, ambles in missteps. It was a misstep for him to publicly reminisce on his cozy relationships with staunch segregationist senators. It was also a misstep to oppose busing, and thus, to oppose legally sanctioned education equality. But despite Biden’s track record of missteps, he continues to get back up and lead the pack. I could say the same about other candidates. But for some reason, Harris’ missteps ended her campaign.

Data show that African American candidates do worse among white voters than black voters in federal elections. One study published at the University of California San Diego suggests that black Democratic candidates are often seen as being less competent and more ideologically extreme than their white opponents, despite their similar policy positions. White candidates, therefore, are seen as more electable than black candidates.

Let’s consider what might be your biggest objection to my argument: the election and reelection of Barack Obama, which, to some, would suggest race plays little to no factor in a candidate’s viability. But Obama’s election did not indicate a post-racial electorate, per se. Rather, a message of hope coupled with a stagnating economy allowed Obama to build a wide-ranging coalition, many of whom were working-class whites in Rust Belt states whose economic woes were shared across racial lines. Obama’s strong support from states like Michigan and Pennsylvania could be more plausibly explained by economic self-interest on behalf of white voters than a shift in racial attitudes.

And beyond that fact, this year is not 2008 or 2012. Voters’ notions of electability, especially at this time of heightened polarization and racial animus, gives white candidates an immeasurable advantage over candidates of color. It is imperative we acknowledge that these competitions, where the stakes are so high and the outcomes so consequential, are not based solely on the merits; they often unfairly factor in race.