It’s a familiar situation: A bombastic populist head of state with a chaotic mop of blond hair faces reelection. It’s something many of us have been thinking about here in the U.S., even with our general election still close to a year away. But this story isn’t about America — it’s about Britain.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson faced reelection last month. Like President Donald Trump, Johnson is a divisive figure, championing populist policies like Brexit and bringing a decidedly flexible sense of ethics to Downing Street. Just days before the election, Johnson’s approval rating stood at around 36 percent, with 56 percent disapproving — not so different from Trump’s dismal approval ratings, which currently stands at around 42 percent approval and 53 percent disapproval.

Both heads of state are unpopular among their constituents. But here’s the catch. Despite his unpopularity, Johnson won reelection. And not just that — his Conservative Party won by the largest margin since 1987, when none other than Margaret Thatcher headed the party.

How did such an unpopular leader secure such a resounding victory? The answer seems to lie with his opponent, Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn. Since 2015, when the hard-left Corbyn startled the Labour establishment with his victory at the leadership polls, he has tried to pivot Labour sharply to the left.

Corbyn arose from the far-left wing of the Labour Party, and is often perceived to be an extremist. He’s supported various despotic regimes on grounds of anti-imperialism, ignited a crisis over anti-Semitism in the Labour Party and even freely admitted to divorcing his wife after she proposed they send their son to private school — Corbyn favors the abolition of private education. Add to that his opposition to NATO, his previous Euroscepticism and his plans to nationalize major industries, and you get a thoroughly unusual and controversial politician.

Perhaps Corbyn’s extreme views help explain why his favorability ratings were even more abysmal than Johnson’s. Just days before the election, a mere 24 percent of Britons voiced approval of Corbyn, with 68 percent disapproving.

Faced with an unpopular opponent drawn from one extreme of the political spectrum, Johnson’s Conservatives swept to victory, seizing victories in working-class districts that had for decades voted reliably for Labour. The Labour Party suffered its worst defeat election in over 80 years.

Corbyn has promised to resign in the wake of the election. But it’s too late. Boris Johnson is now a prime minister with a strong mandate. Brexit will likely happen, and the UK will stray down a populist course for the foreseeable future.

Trump has a lot in common with Johnson — he’s a right-wing populist with strong nativist tendencies, and he presents a real threat to the pluralistic liberal democracy that has long defined both Britain and the U.S. He’s also unpopular, and the Democrats are in a prime position to replace him come 2020.

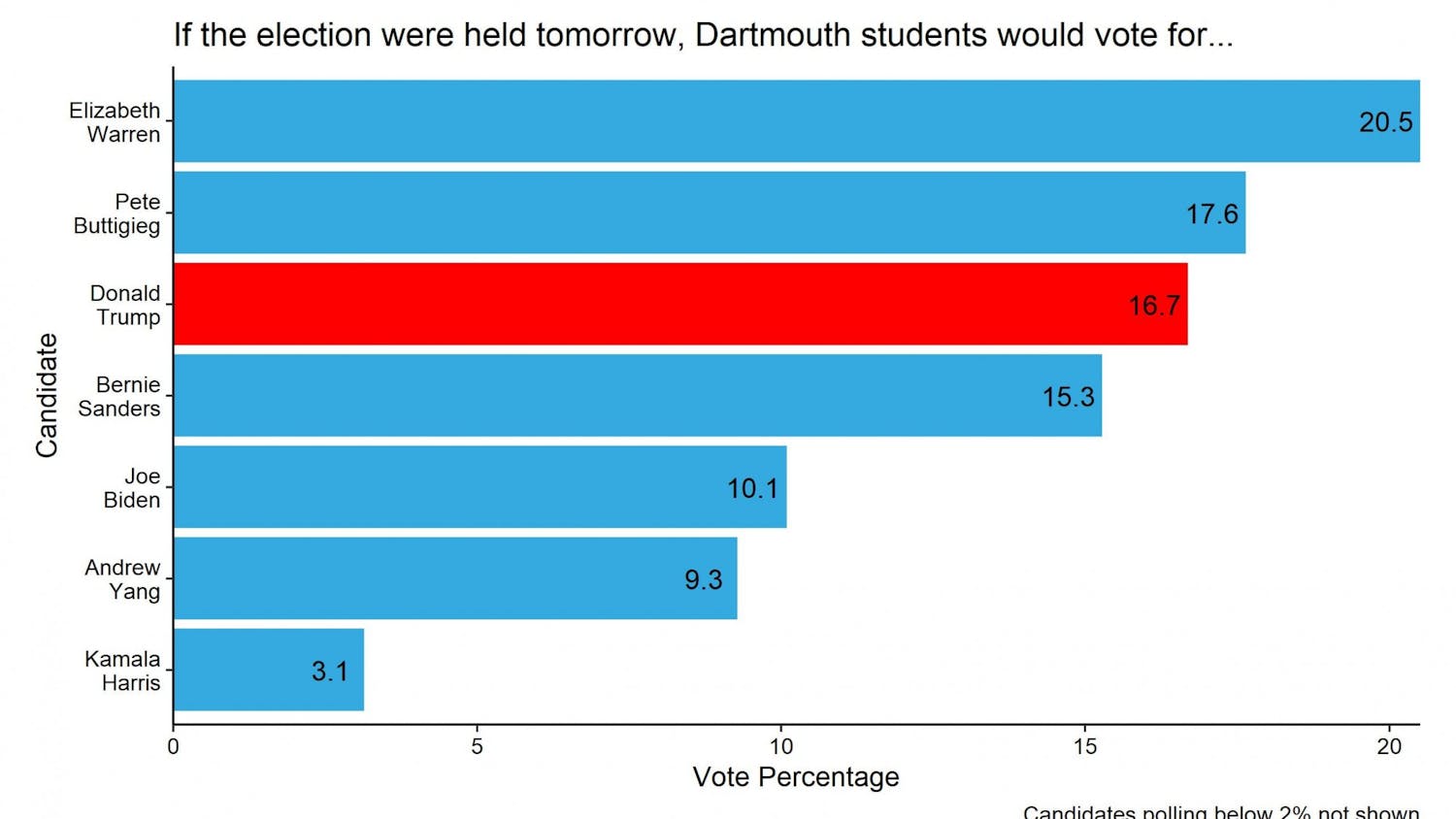

Except that, strangely enough, the Democrats now seem to have their own take on Corbyn. Of course, neither Bernie Sanders nor Elizabeth Warren — who currently poll at second and third in the Democratic primary, respectively — hold views nearly as extreme as Corbyn’s. The two progressive Democratic candidates more or less want to increase government services and regulation, a relatively undramatic social-democratic platform that, while somewhat unusual in American politics, would not look out of place in a mainstream European center-left party.

But let’s put that statement in context. Though Warren and Sanders may fall well to the right of Corbyn, the two senators sit on the very leftmost fringe of America as a whole. In the 115th Congress, Warren had the single-most liberal Senate voting record, with Sanders just behind her at number four. Though their ideologies may not match Corbyn’s, their relative positions on the political spectrum do. And that spells trouble.

Most Americans don’t consider themselves liberal; in a 2019 Gallup poll, just 26 percent of respondents called themselves liberal, while 35 percent identified as conservative and another 35 percent as moderate. Based on Americans’ own stated ideologies, the progressive candidates appeal to a smaller fraction of the electorate than do moderate candidates, making progressives less competitive in the general election.

Now is not the time to take risks. Especially given that the GOP is favored to maintain control of the Senate in 2020, the details of who has the most progressive policy platform matter little. What matters is defeating Trump.

There are a number of promising mainstream candidates — like Joe Biden, Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg — running for the Democratic nomination. If we’re to learn any lesson from the Labour Party’s catastrophic loss at the polls, it’s this: Let’s nominate a mainstream Democrat. Even if your ideals align more closely with Warren or Sanders, now is the time to vote strategically. The stakes are too high to risk another four years of Trump.