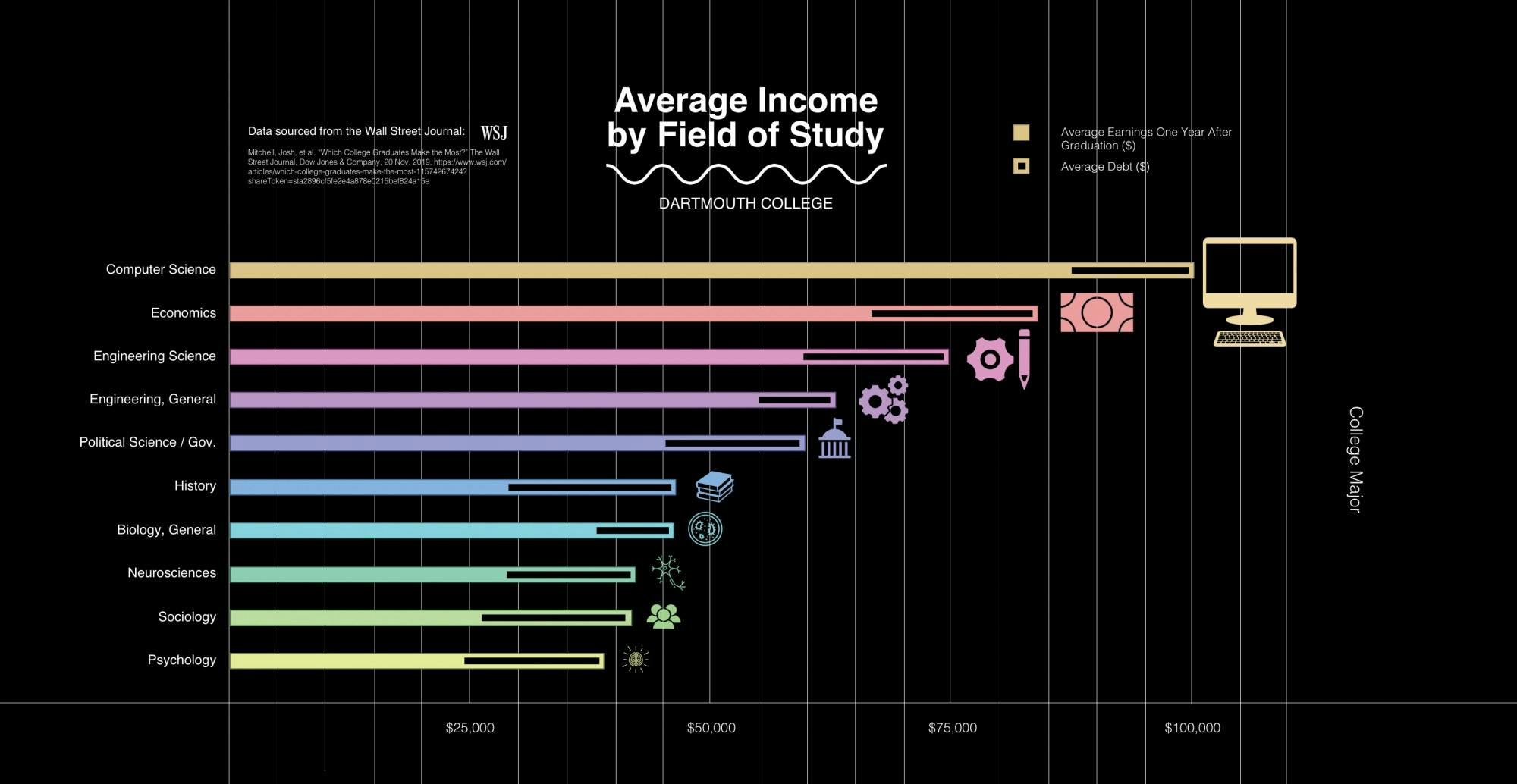

A Dartmouth graduate’s average salary can range from $38,900 to $100,500, while student debt at the College ranges from $7,500 to $17,007 depending on a choice of major, according to government data published in the Wall Street Journal.

The data, released by the U.S. Department of Education last fall, is unique in that it distinguishes earnings by major. Previously, the DOE released single, school-wide statistics irrespective of degree.

In total, 15 percent of colleges in the data set showed a debt average higher than their earnings average, and elite institutions like those within the Ivy League consistently had the highest earnings-to-debt ratio.

The most popular majors at Dartmouth, respectively, are economics, government, computer science and engineering. The highest-earning majors, which correlate with those majors, are, in descending order: computer science, economics, engineering and government. This trend is somewhat mirrored for majors with the lowest debt — engineering majors were shown to have the lowest debt, along with biology, computer science and neurobiology/neuroscience majors.

Computer science majors top the salary rankings at Dartmouth, earning an average of $100,500 yearly. In comparison, computer science graduates at Cornell University make $116,300 in their first year, while those at Brown University make $141,000. Dartmouth students graduating with an economics degree make $84,200, while economics majors at Cornell and Yale University make $67,500 and $81,400, respectively. Dartmouth government graduates are the highest paid among government majors at comparable institutions: they earn $59,000, compared to $45,100 at Cornell and $49,100 at Yale.

The data confirm a reality assumed by many Dartmouth students regarding which majors are most likely to yield higher incomes and debt — a factor often considered by students not only in their choice of college but also in major selection. Robin Martinez ’23 said that these factors played into his college decision as a first-generation college student.

“Ideally, I would need a full ride in order to go to college because I couldn’t get any funding from my family, and I needed to make sure I didn’t come out with a lot of loans,” Martinez said.

Martinez said that his prospective post-graduation earnings were also an important aspect of choosing Dartmouth and his major as well. Martinez said he initially felt stressed in his decision to choose a traditionally well-paying major.

“When I got here, I got a lot of pressure from my parents to do engineering, and that’s not something I like at all,” Martinez said. “We put a lot of pressure on ourselves because we are the first to have this shot, and we want to make it count.”

Despite the initial pressure, Martinez said he hopes to pursue a major more suited to his interests.

“Dartmouth has done a really good job of showing me what is possible in any major, which is something I didn’t understand before coming here,” Martinez said.

First Year Student Enrichment Program director Jay Davis ’90 echoed Martinez’s sentiments. Davis said salary is often an important factor in major choice for many of the first-generation students he works with — students who hope to support their families financially.

“Not thinking about salary is a luxury that often comes with students that are from better-resourced backgrounds,” Davis said.

According to Davis, while salary is an important component of many first-generation students’ choice of major, it isn’t something he typically discusses in his advising work. Instead, Davis focuses more on the interests of each individual student.

“I try to work with students much more about finding their genuine passion,” Davis said.

Davis added that at a high-level institution like Dartmouth, the subtle differences in pay among majors is less important to first-generation students than the overarching need to find a reliable career and support their families.

“Most of the careers that students are looking at are well-enough paid to make a huge difference already for their families,” Davis said.

According to Davis, the data will be helpful for informing students, but the salary statistic should not stand alone, as there are many nuances to finding a secure and enjoyable career.

“If you can have that data, fantastic,” Davis said. “But to not rely on that is what’s important.”

Other students at the College spoke to the extent that eventual salary has played into their academic choices.

A fifth-year computer engineering major, Trevor Colby ’19, said that his choice of major was influenced by the eventual salary he would earn.

“During my freshman year at Dartmouth, I recognized that I would be accumulating a sizable amount of student debt despite generous financial aid,” Colby said. “In my mind, this greatly limited my options for a major. I felt like I had to major in something that would make me easily employable, as well as something that would allow me to dig myself out of the hole of debt that I was diving into.”

Economics professor Bruce Sacerdote said the DOE’s ultimate goal in releasing the data, known as “College Scorecard,” is to guide students in choosing a college that will allow them to graduate without debt. Sacerdote said the government gathers tax and administrative data from the Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service to come up with the data. He said he believes it is valuable information for prospective and current college students.

“If college students and families take advantage of this information, it could help steer students toward some of highest value-added institutions with excellent graduation rates,” Sacerdote said.

Sacerdote added that while the data can provide helpful guidance, what a student chooses to major in is often not a career-defining decision.

“Dartmouth’s focus on a liberal arts education continues to pay large dividends,” Sacerdote said. “Some of our most famous graduates have majored in one field and made their mark professionally in a completely different field.”

Government professor Dean Lacy concurred with Sacerdote, saying that while the data are helpful, the information should not be used as the sole guide for choosing a major. Variables outside the government statistics also hold important weight.

“There is a great deal of unmeasured, individual-level variation in salaries,” Lacy said. “Salaries also don’t capture job satisfaction, job security, workplace climate and other things that make a job rewarding.”

Lacy added that the value of a well-rounded education exceeds that of any particular choice of major.

“A broad, liberal-arts background is a better foundation for a career than a narrow, specialized background,” Lacy said.