At a time when President Donald Trump enjoys a nearly 90-percent approval rating among Republican voters, Mark Sanford has found himself in a battle for the soul of his party. A former governor of South Carolina and six-term member of the U.S. House of Representatives, Sanford is one of three former Republican elected officials challenging Trump for the 2020 Republican presidential nomination.

Sanford’s career in public life has seen its share of ups and downs. First elected to Congress in 1995, Sanford left the House in 2001 and was elected governor of South Carolina two years later. With an extramarital affair ending his governorship in controversy in 2011, Sanford was reelected to his old congressional seat in 2013. After Trump’s election, Sanford became one of the highest-profile Republican critics of the president, which analysts believe was likely the key factor in his defeat by a Republican challenger in the 2018 primary election.

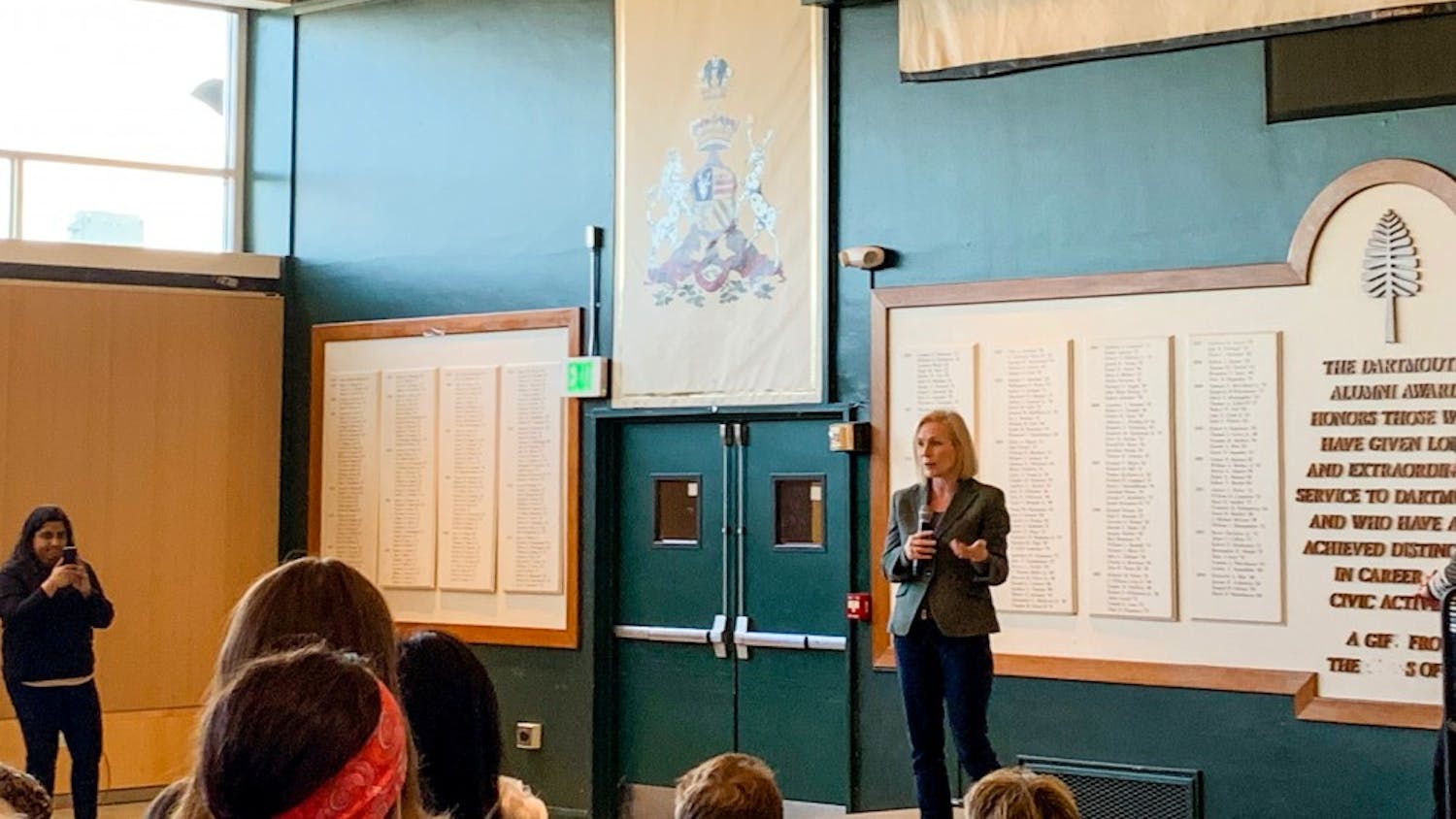

During a visit to Hanover last week, Sanford sat down with The Dartmouth for an interview on the current state of Republican Party, the changing fortunes of his career and what he believes is the most important issue facing future generations.

Do you think the Republican Party has permanently changed as a result of Donald Trump’s election?

MS: I don’t believe there is a permanent change in the body politic. Jefferson was eloquent about how there was, in essence, a battle line with government on one side and liberty on the other. If you look through the pages of history, there’s constantly been a tension between security on one side and freedom on the other. The Republican Party and Democratic Party are simply vehicles for a much larger debate that has been taking place since the beginning of time on security versus freedom. I think that the Republican Party has been harmed, and there will be lasting harm, given where the President has taken the party. If you think about it in marketing terms, I don’t know what kind of toothpaste you use, but you probably don’t change it regularly — you get used to what you’re used to. Not because it’s necessarily the best brand ever, but because it checks the boxes and we can’t make unlimited decisions on every little minute decision in our lives. Brands have lasting value in that they become a default decision based on largely accomplishing a basket of needs. Political parties are the same. And where I do think there has been lasting damage done is in regard to the brand of the Republican Party — what it stands for.

Since World War II, three presidents have lost their bids for reelection. In each of those elections, the incumbent president faced a high-profile opponent in the primaries. If your candidacy or one of the other candidates opposing Trump catches on and creates a serious fight for the Republican nomination, do you think that would essentially hand the general election to the Democrats?

MS: It could. And so a number of people have been critical of me, saying, “Well, wait a minute. This is just about making sure a Democrat gets in to office.” I say, that’s not at all the case. Competition is the American way. Ideas are refined and made better by competition. And the idea that the Republican Party is going to wait for the big contest in November is completely contrary to what you see with a whole host of football teams across New Hampshire competing all week long with scrimmages, with practices — getting ready for the big game on Friday night. I think, in fact, we’re a better Republican Party if we have a robust debate of ideas, whether I’m the eventual nominee or someone else is. I think the Democratic Party is having a robust debate over what it means to be a Democrat, and we should have a concurrent debate on the Republican side. And rather than weakening the party, it makes it stronger.

The other two Republicans challenging Trump publicly favor his impeachment. You favor censure over impeachment; can you explain why and how you came to that conclusion?

MS: I think we need to decide whether we’re after a merit badge or whether we’re after ending much of what Trump has represented or instituted. For me, I would support ending it. If you’re after that, then I think you say, “What’s the most effective way of ending it?” If you go the route of impeachment, what we know — based on not just what Mitch McConnell has telegraphed, but on what he’s actually said — is that impeachment is going nowhere in the Senate. So what you know is, going in, he’ll be levied with charges on the House side that won’t go anywhere in the Senate: What’s that allowing him to do? He then says, “Told you I did nothing wrong!” That’s a much more clouded message for the voter than the Congress taking a definitive stance, saying, “Look, we know we can’t remove you, but we’re going to condemn you for what we see as wrongful behavior.” I think from an electoral standpoint, it’s more powerful. If you want to end Trumpism, then you’ve got to end it at the ballot box. And let’s say impeachment happens: Then he becomes a martyr. And the roots of what created the Trump phenomenon continue to exist in the future. If we move on with impeachment, the giant sucking sound will be every bit of political oxygen going out the room on any issue that might be discussed that’s real to our lives. And instead, we’re going to spend the next couple of months just talking about impeachment.

Your career has had ups and downs. How have you learned from failure?

MS: A lot. You learn so much more in failure than you do in success. What happens in the wake of failure, particularly public failure, is an amazing level of soul-searching that causes you to recalibrate. I think that one of the things that’s lacking in all walks of life is humility to say, “I know what I believe, but let me understand where you’re coming from.” I think you learn a level of empathy. I used to read the paper and think, “Loser. Loser. What was that guy thinking?” And now you go, “But by the grace of God go I.” You recognize that we all have feet of clay, and there’s something that can trip up anyone. I could go down a laundry list of different lessons learned that were invaluable to me. And in fairness, this is in strong contrast to what the President said. The President said, “There’s nothing I regret in life.” I’m thinking, “What kind of planet do you live on?” Because the reality of our shared human experience is, we all have a chapter of our lives in which, if you live long enough, you wish it didn’t happen. But that’s not how life works. And so the question is, do we learn from those moments and have at least a chance to become the better for them?

What do you believe will be the most important issue facing the next generation — and if elected, how would you approach it?

MS: The big, big issue that’s not being discussed — because climate change and other issues are being discussed — is the debt and the deficit and government spending. We are walking toward the most predictable financial crisis in the history of man. It is going to have profound implications in your life and the lives of other students here. And no one is even talking about it. It will be as big as the Great Depression. It could mark the end of our civilization if we don’t play our cards right. At minimal, it will be incredibly destructive in economic terms. I would just say, read the pages of history. Historically, what has extinguished most civilizations has been getting ahead of their skis on deficit spending and not being able to reconcile those differences politically. I think that’s the bad movie we’re headed toward that we need to be talking about, and it’s a good part of what my campaign is about.

And how would you address that issue?

MS: The first step is to recognize there is a problem. It’s remarkable. On the Democratic side, there is zero debate. How exactly are you going to pay for that stuff? On the Republican side, there’s just complete denial on the debt and deficit, which at least we used to talk about in the Republican Party. The first part of leadership is plowing the field before you plant it, and if I was president, I would hold a long series of town hall meetings on this subject so we can educate the public. If you got buy-in, where people actually said, ‘This is a systemic threat to our civilization, this is a real problem,’ — it’s amazing what the American public has done over the years. If you got to that point, would people give up a penny out of every dollar of federal benefit? I think they would. And if they did, in five years, you’re back to a balanced budget.

One of the biggest issues college students are concerned about is student loan debt. How would you address this issue as president?

MS: Let’s be clear: It’s raw election pandering to go out and say, “Let’s just wipe out all student debt.” In the short run, I think it’s prickly, because I don’t think it’s equitable or fair for the preponderance of folks out there who don’t have a college degree to subsidize the repayment of folks who entered into contractual agreements. I’m not for that. I do think we need to rationalize our system. I think we have a system that pushes too many people into college. I saw this when I was governor. We worked hard with tech programs to say, let’s value people who have a capacity to work with their hands. God makes us all different, and we shouldn’t channel everybody into a college prep program when in fact a tech prep program may be suitable for many people and may take better advantage of their skills. And so when you look at a lot of folks who go the college route, they drop out, end up with large amounts of student debt and do not get the payoff. And so I think you ought to have a more rational system that encourages both choices in a way that the present system does not.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.