An accomplished researcher and professor, Dave Bucci not only prioritized his undergraduate teaching, but also brought encouragement, enthusiasm and kindness to every interaction he had with students and colleagues.

“He was the most beloved member of our department,” said psychological and brain sciences professor and director of graduate studies Thalia Wheatley. “He was so affable, this big bear of a guy. He had nicknames for everybody — he would ask people about their kids. He was loved.”

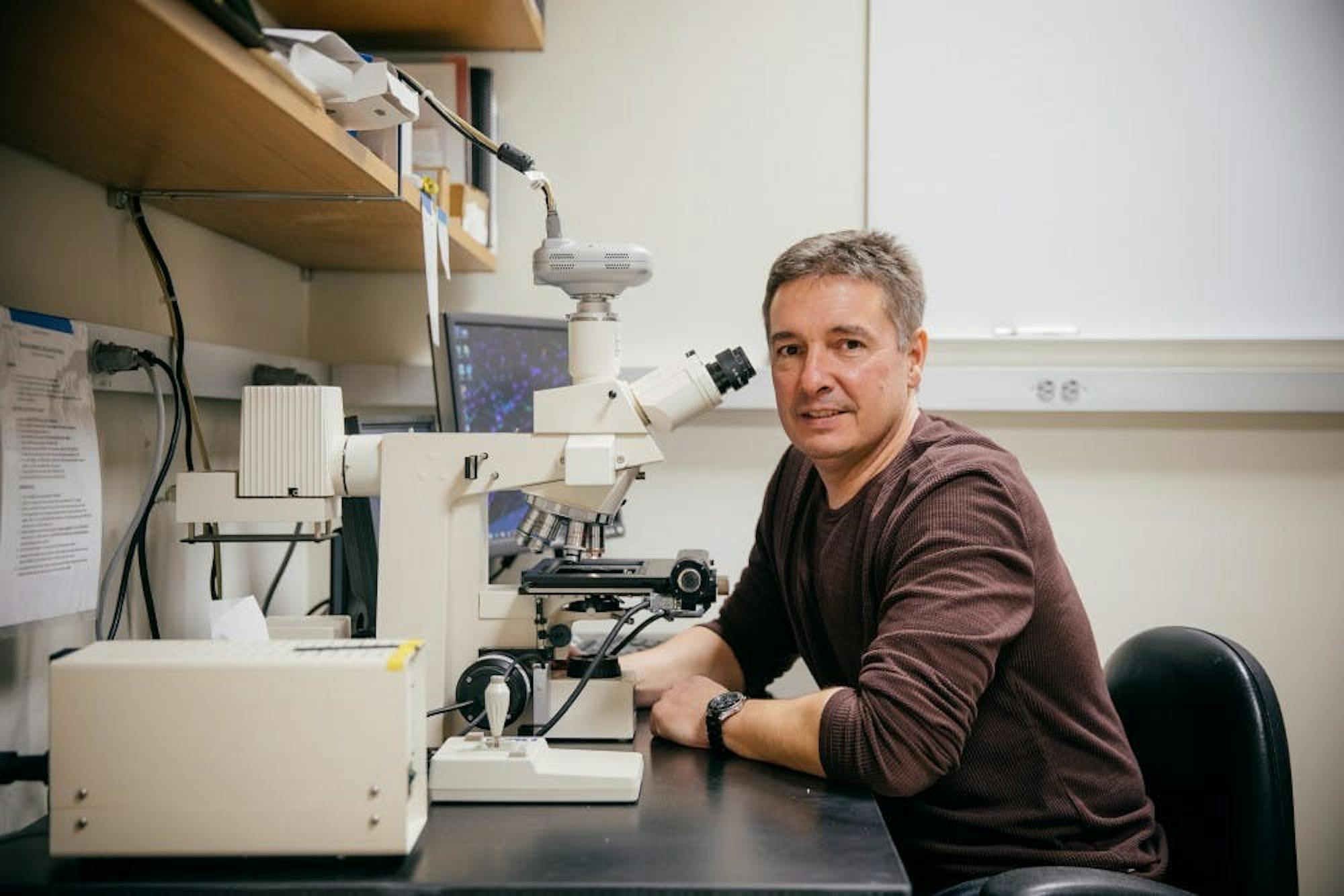

The former chair of the PBS department, Bucci died by suicide at age 50 on Oct. 15. A visitation was held on Oct. 24 at the Knight Funeral Home in White River Junction, VT, followed by a funeral mass on Oct. 25 at Saint Denis Church in Hanover. He is survived by his wife, Katie Bucci; his children, Ava, Joshua and Lila Bucci; his parents, John and Barbara Bucci; and his brother and sister, Christopher and Cheryl Bucci.

Bucci was born on Nov. 28, 1968 in Tarrytown, NY and grew up in New Fairfield, CT. Throughout his youth, Bucci demonstrated a strong work ethic and a passion for the sciences. He ultimately received his bachelor’s degree in biology and psychology from Wesleyan University and his Ph.D. in neurobiology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

After receiving his Ph.D., Bucci worked as a postdoctoral fellow in the Burwell Laboratory — a lab dedicated to behavioral research on rats that can be applied to human cognition — at Brown University from 1998 to 2001. He worked closely with undergraduate students while there.

“There were no other graduate students, so Dave was really the one that showed me all the different approaches that you take in the lab,” said Michael Saddoris, a neuroscience professor at the University of Colorado Boulder who was an undergraduate student in the Burwell Lab. “Going from scratch to actually getting started [on research], there’s a lot to learn, and there’s a pretty steep curve.”

He noted that Bucci’s work in the lab was far from easy and required a substantial time investment in order to help undergraduate students.

“You don’t really appreciate what a postdoc does until you do it yourself, and most people don’t do that,” Saddoris said. “Most people don’t engage with the undergraduates with that level in terms of mentorship and collegiality.”

Bucci, he said, was outgoing, supportive and always willing to assist.

The two remained in touch after Bucci left the lab, and Saddoris said that Bucci was always happy to offer him advice and support.

“It was really encouraging to have that sense of mentorship that lasted for 20 years after working with him,” Saddoris said.

Alyssa Letourneau, another undergraduate student who worked in the Burwell Laboratory with Bucci, described Bucci as a “bright-eyed, bushy-tailed postdoc,” adding that he was always encouraging even though she eventually decided she did not want to pursue research.

After her graduation, Bucci offered Letourneau a job helping to set up a new lab at the University of Vermont in 2001. She recalled a story in which the newly-installed water purification unit in the fourth-floor lab sprang a leak, dumping thousands of gallons of water into the building. She added that Bucci approached the situation — and lab repairs — with humor, enthusiasm and dedication.

“Some of my fondest memories are of us having gotten through [that] big project and having gotten all that done,” Letourneau said.

The two of them also stayed in touch after parting ways. She attended his wedding, she remembered, and they often exchanged emails about Dave Matthews concerts — they were both fans — that he attended.

“He would always send me a little email or a message and say ‘I went to Dave Matthews, couldn’t help but think of you,’” Letourneau recalled. “He loved to play the guitar, and he would definitely try to play some of that music.”

In 2004, Bucci accepted a position as an assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at the College. In 2015, he was promoted to chair of the PBS department and was named the Ralph and Richard Lazarus Professor of Psychological & Brain Sciences and Human Relations in 2016.

His work for the College extended beyond teaching undergraduates — he also served in the graduate program in Experimental & Molecular Medicine, the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience and the Center for Technology and Behavioral Health at the Geisel School of Medicine. Additionally, his lab, the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory Laboratory, allowed undergraduate students the opportunity to investigate the behavioral and neurobiological factors that regulate learning and memory. Outside of Dartmouth, Bucci was an elected Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science and the American Psychological Association and received numerous awards for his research, teaching and mentoring. Over the course of his academic career, Bucci was awarded nearly $7 million in grant funding for his research as a principal or co- investigator.

Bucci served as an influential figure for many Dartmouth students during his tenure. In many cases, he altered the trajectory of his students’ careers — whether by inspiring students in the classroom or fostering community within his lab — according to lab alumna Sarah Miller ’19.

Miller said she met Bucci during freshman orientation, although she was already familiar with his work prior to attending Dartmouth. When she expressed interest in his research, she said Bucci reacted with elation and enthusiastically invited her to coffee.

“It was my first taste of how great professors can be here at Dartmouth and how exciting it is to have a conversation with someone who is passionate about the same things that you are,” Miller said. “It was the same for all four years. He was really inspiring. He would always give me a high five in the hallway and ask me how I was doing and he just cared — not just for me but everyone. He was just a sunshine.”

Miller added that she hails from a “close-knit town” and, when she came to Dartmouth, she worried about not finding the sense of community she associated with home. Instead, she said that Bucci fostered a community “and then some.”

For instance, during Miller’s freshman summer, Bucci invited his lab mentees to his wife’s concert in Norwich, VT, said Miller.

“The sense of community was something you felt throughout your entire body,” she said. “It was palpable — you could feel it in the air. And it was [lab group outings] like that, that created a strong community.”

Despite never having worked in Bucci’s lab, Jesse Gomez ’12 said he felt inspired by Bucci. Gomez said he intended to major in physics before taking Bucci’s introductory neuroscience course. Bucci’s enthusiastic style of teaching was contagious, according to Gomez.

“A lot of other science classes are very different — they are very tough and they are meant to weed people out,” Gomez said. “But [Bucci] wanted you to learn the material and he was always happy to answer questions.”

Gomez said he ultimately changed his major to neuroscience — a decision he said he largely attributed to Bucci.

Even fleeting interactions with Bucci left a lasting mark, according to Hannah Raila ’10. Raila said she wandered into Bucci’s office during her sophomore year, hoping to discuss career paths in psychology. Ten years later, Raila has a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and plans to apply to faculty positions.

“It was a life-changing interaction, and was the first time that I seriously considered going [to graduate school for psychology],” Raila said. “That brief memory of him dedicating his time to a lost and confused [undergraduate] student has stuck with me when I envision the type of academic mentor that I think we could all aspire to be.”

Bucci’s colleagues in the PBS department admired him as a dedicated scholar, brilliant researcher and good friend.

“In terms of his work, undergraduate teaching was just the biggest source of joy in his life,” Wheatley said. “He loved teaching students in the classroom, getting them to think, he loved when undergraduates in his lab discovered something and got excited about science. This is just the thing that made him the happiest, in terms of his work.”

Wheatley also worked with him in an administrative capacity and noted the impact he left on the department. She pointed out that he served an extra year beyond the normal three-year term as chair of the department because “he was so good at being chair.”

“Everybody loved him because he was fair,” Wheatley said. “Even if it [came] at great personal cost, or cost him lab space, or whatever, he was always focused on what is in the best interest of the department, what is the fairest thing to do, how do we work together on this.”

PBS professor Katherine Nautiyal said that she teaches at Dartmouth because of Bucci.

“[Bucci] climbed the ladder to an endowed chair with grace and integrity, and always turned around to help up the next generations,” Nautiyal said. “[Bucci] was kind, undeniably respectful, undoubtedly loyal and one of the most open and honest people I have known. It’s hard to imagine how we’ll recover from this loss.”

Outside of academia, Bucci relished the opportunity to work with children — especially through coaching Little League baseball — according to his fellow assistant coach Steve Smith.

“One of the things I appreciated about him was that he was a big deal at Dartmouth, but in our interactions, he never acted that way,” Smith said. “He was always warm, funny and approachable. He was never pretentious, even though he could have easily come across [that way] because of his achievements.”

Smith and Bucci shared a coaching philosophy — they both rooted for the team’s competitive success, but, above all, they wanted the players to support each other.

“As a parent, I was always so happy to see my son interacting with [Bucci] because I have such respect for him,” he said. “He had such approachability and was so down-to-earth.”

A number of notes, cards and flowers have been left at the door of Bucci’s office. Additionally, Wheatley has created a website, davebuccimemorial.com. where those who knew him can leave memories and stories.

“Above all, he loved his family, working with his hands and inspiring his students,” Wheatley wrote on the website. “And he was beloved, by all of us.”