It was a gray day in Piazza Benedetto Cairoli, a small park just down the street from Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori, where I shared a bench with Olivia Goodwin ’21. The topic of that day’s chat? Pronouns.

This fall, I’m working as the director’s assistant for the Italian Language Study Abroad + program in Rome, and I’ve been thinking a lot about pronouns lately. Italian, like other Romance languages, is a gendered language. Every noun and adjective has a grammatical gender, usually indicated by the vowel with which a word ends — “o” is usually masculine, “a” is usually feminine, and “e” and “i” can be either depending on the specific word and whether or not it’s singular or plural. There are exceptions, of course, but the point remains that, as far as the grammar goes, there isn’t much wiggle room for a neutral or non-binary gender to exist.

That’s why I wanted to speak to Goodwin. In English, Goodwin uses “they/them/theirs” pronouns, and I was interested in learning about their experience living in a language that doesn’t have an equivalent to the singular they.

It probably goes without saying that their experience with Italian has been a little complicated. In such a rigidly gendered language, what’s a person who identifies as neither a man nor a woman to do?

“When I decided to take Italian, I knew it was a very binary language,” they said. “But I didn’t really care because I liked it, and I liked Italian culture.”

In spoken Italian, Goodwin uses the feminine pronoun “lei” and the corresponding feminine nouns and adjectives — that is, an Italian speaker hearing Goodwin speak would probably assume they identify as female based on their word choice. While it’s not ideal, they explain that they didn’t want to take the risk of presenting themself as male, especially without knowing the cultural connotations of being a man in Italy.

In written Italian, however, there’s a bit more flexibility. Goodwin tends to use either an asterisk or an arroba (fancy word for “at sign”) in place of gendered vowels. So, while one would usually call a boy a “ragazzo” and a girl a “ragazza,” they might instead write “ragazz*” or “ragazz@” when referring to themself.

It’s not unlike what happens in Spanish. At Dartmouth, the word “Latinx” is usually used instead of Latino or Latina, even if the pronunciation of the word isn’t clear to Spanish speakers who don’t speak English. (In some Spanish-speaking countries, the ending vowel “e,” as an alternative for the “x,” is also gaining some traction as a non-binary gender marker.) Like in Italian, however, no option for a gender-neutral ending in Spanish has become universally accepted. Even this summer, when I worked at a hostel in Puerto Rico, people from outside North and South America generally seemed unfamiliar with the term Latinx.

While Goodwin has to think very intentionally about how they speak about themself in Italian — even going so far as to intentionally use words like “person” instead of man or woman, which still has a grammatical gender but whose meaning doesn’t imply a person’s gender — they said they have also had a positive experience as a whole with Italians respecting their identity. For example, after explaining their gender identity in an introductory letter to their host family before arriving in Italy, they received an email reply in which their Italian host mom went out of her way to use the gender-neutral asterisk.

Toward the end of my conversation with Goodwin, we got interrupted by a man who had been sitting on the opposite end of the bench. In a decidedly British accent, he said that he was glad to have overheard us and that he hasn’t heard many people discussing pronouns in depth in Europe. On my way back home, I kept thinking about pronouns and how, even in English and in the United States, conversations about them can be tricky.

This was my third year volunteering for First-Year Trips, this time around as one of the outreach coordinators. Since last year, Trips has had a policy of using pronouns when volunteers and new students introduce themselves. The first few times I introduced myself on Trips this year, I sometimes forgot to include my pronouns, but by the end of Trips, I didn’t miss a beat: “Hey everyone! My name is Cris, my pronouns are he/him/his, and I’m a ’20 from just outside of Fort Worth, Texas.”

It’s no secret that not everyone supports this policy; I’ve heard comments about how some people think repeating their pronouns over and over again is overkill, especially if everyone in a given group is cisgender. On the flip side, I’ve also heard concerns that asking people to say their pronouns can be alienating if only one person in a group is transgender or non-binary. And if someone arrives at Dartmouth while still being in the closet, being asked to give pronouns might present a difficult choice: come out to a group of strangers or remain closeted.

It’s also no secret that, once Trips is over, most people don’t seem to keep including their pronouns in introductions. Sure, I’ve been asked my pronouns on surveys and forms, and every now and then I’ll notice people introducing themselves with their pronouns — more often than not if I’m at an LGBTQIA+ event or with friends who aren’t cisgender. But for the most part, mentioning pronouns seems to fade away as soon as classes start.

After interviewing Goodwin, I realized that I wasn’t even sure if introductions with pronouns extend to Orientation Week. I then reached out to Sruti Pari ’20, who was a part of O-Team both last year and this year. She told me that O-Team did make an effort to use pronouns during group introductions, but not always when talking to ’23s one-on-one.

Pari believes that one reason why using pronouns hasn’t quite gone mainstream in the Dartmouth community is because experiences like Trips and Orientation Week are simply too short-lived. If upperclassmen made an effort to keep using pronouns in their various clubs and communities after the beginning of the year, she said, maybe the continued exposure would help it catch on.

“Even though we do introduce ourselves with pronouns during things like Orientation and Trips, I feel like a lot of kids might still have that mentality of, ‘Oh, I’m not at a queer event or I myself am not queer, so I don’t really feel the need to include my pronouns,’” she said.

Are all these efforts to encourage new students to say their pronouns futile? Perhaps not. Brandon Zhou ’22, who went on a First-Year Trip last year and was a volunteer on Hanover Croo this year, was the youngest student I interviewed and the only one who had been exposed to introducing pronouns before starting college. He explained that he had seen people at other colleges and universities do it, so it already felt normalized. When he got the chance to explain pronoun usage to others as a Trips volunteer this year, he said he felt like he was helping foster a supportive environment for new students.

“As a Trips volunteer this year, I feel like facilitating [introductions with pronouns] and explaining to people what they are was a very different experience,” he said. “I feel like I played a larger role in creating an inclusive community.”

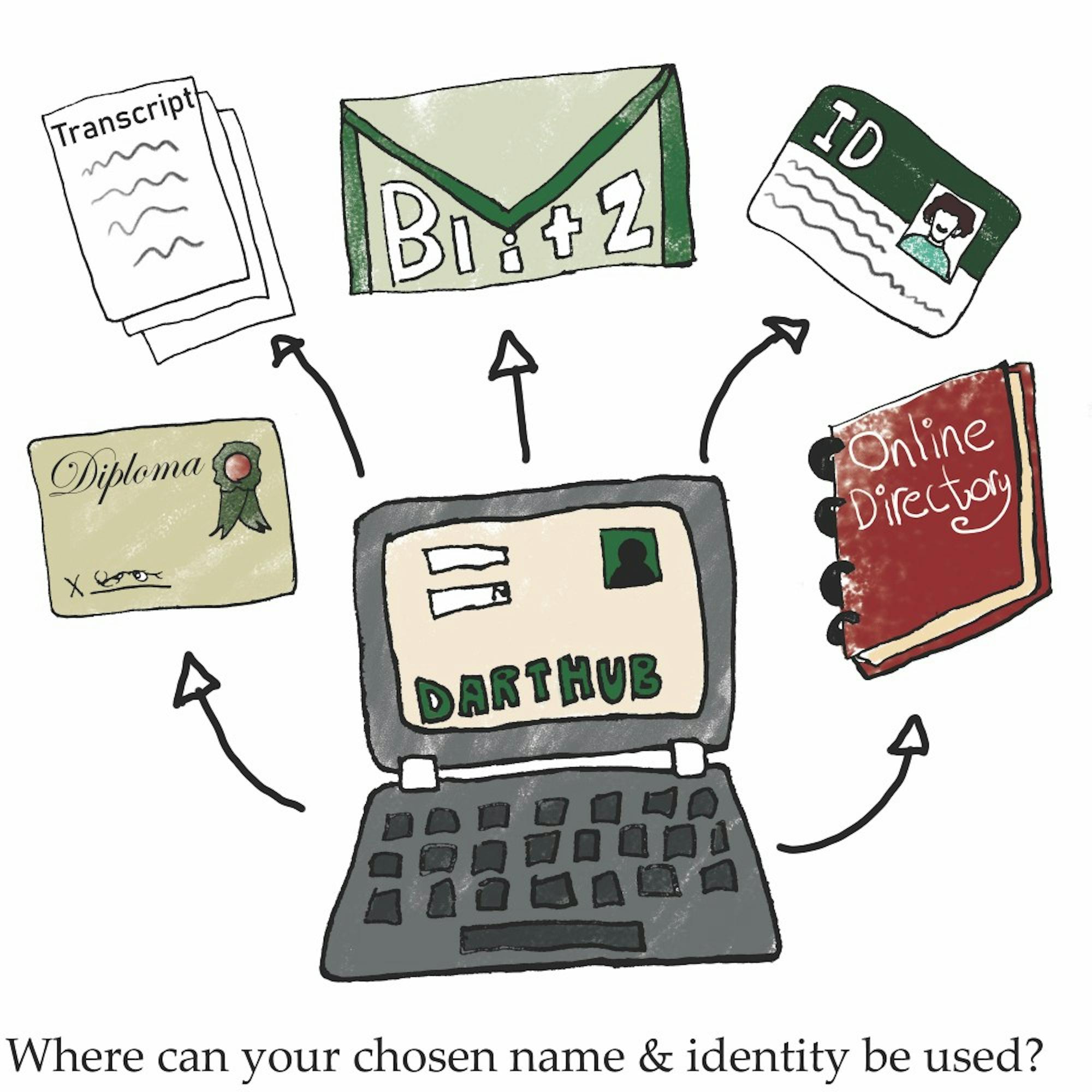

Thankfully, student groups aren’t the only ones thinking about pronouns. Earlier this month, DartHub received an update through the new Chosen Name and Identity initiative that allows students to customize how their name, gender identity and pronouns appear in places such as the Online Dartmouth Directory and transcripts. Registrar Meredith Braz led the initiative in collaboration with Information, Technology & Consulting, and she answered some questions about the policy in an email statement.

According to Braz, a significant obstacle to overcome was simply the online systems that stored students’ information. The old version of Banner, which preceded DartHub, didn’t offer support for students’ chosen names, and the process that the registrar’s office had previously used to support transgender students was “extremely clumsy,” she wrote. In addition to waiting for an update from Ellucian, DartHub’s vendor, the registrar’s office also had to coordinate the Chosen Name and Identity initiative with offices that used different systems altogether.

“Safety and Security and the ID Card Office, which use systems other than Banner, had to figure out how to support students given their particular system and mission,” Braz wrote. “We had to work with an outside vendor to allow for Chosen Name on transcripts.”

Braz also explained how the options available in the online dropdown menu were the result of recommendations and feedback given by students, professionals and the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, as well as national best practices. There is also the option to write in your own pronouns, which Braz specifically pointed out when asked about students who may use more than one set of pronouns.

Having autonomy over how others see your personal information, making an effort to include pronouns when you introduce yourself, finding a way to express your gender identity in a language whose grammar doesn’t quite want to cooperate — none of these are magic solutions to making everyone feel safe and welcome. But they’re something. Baby steps.

At the end of a long day thinking about pronouns, I then logged into DartHub to select my own gender identity and pronouns. That’s something, too.