Last Friday, actress Felicity Huffman was sentenced for her role in the college admissions scandal uncovered by Operation Varsity Blues. Huffman confessed to paying $15,000 for an SAT proctor to change her daughter’s incorrect answers before her test was submitted a pretty obvious case of education fraud.

Prosecutors in Huffman’s case argued in favor of jail time for the parents implicated in Varsity Blues, pointing to the 2009 case of Kelley Williams-Bolar, an Ohio woman who was sentenced for registering her children in a suburban school district to avoid the Akron school they would have otherwise attended. The actions that Huffman and Williams-Bolar took are quite different, but they shed light on the same problem: discrete portions of our education system monopolize the resources that emerge from economic competition and distort the distribution of the benefits. And it all happens without breaking a single law.

To me, Dartmouth’s admissions statistics basically make the argument on their own. For students offered admission to the Class of 2023, 48 percent were eligible for scholarships from the school. That means that just over half of freshmen are paying the full $76,000 sticker price this year. While students whose families earn less than $100,000 per year in income are provided free tuition, students from the upper class, which the Office of Admissions defines as a household with greater than $200,000 in annual income, makes up a whopping 60 percent of the admitted Class of 2023. Dean of admissions and financial aid Lee Coffin told The Dartmouth that these numbers reflect the admissions office “deliberately focusing” on socioeconomic diversity. No offense to the ’23s, but that claim may not be true.

But Dartmouth is far from an outlier. In 2017, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a paper on the role that college attendance plays in intergenerational income mobility. The study concludes with a framing similar to my own opinion on the matter: Patterns of university attendance don’t create structural inequality on their own, but they mirror it perfectly. A child whose parents are in the top one percent are were more than 75 times more likely to attend an Ivy than one whose parents are in the bottom income quintile. And according to a study done at Duke University in 2013, 45 percent of American billionaires attended a school where the average freshman placed in the top one percent of standardized test scores. While we might like to think that it takes nothing more than a combination of motivation, hard work and careful preparation to get to college, that assessment forgets the socioeconomic circumstances that allow an individual to even consider an elite institution as a possibility, let alone to be a competitive applicant.

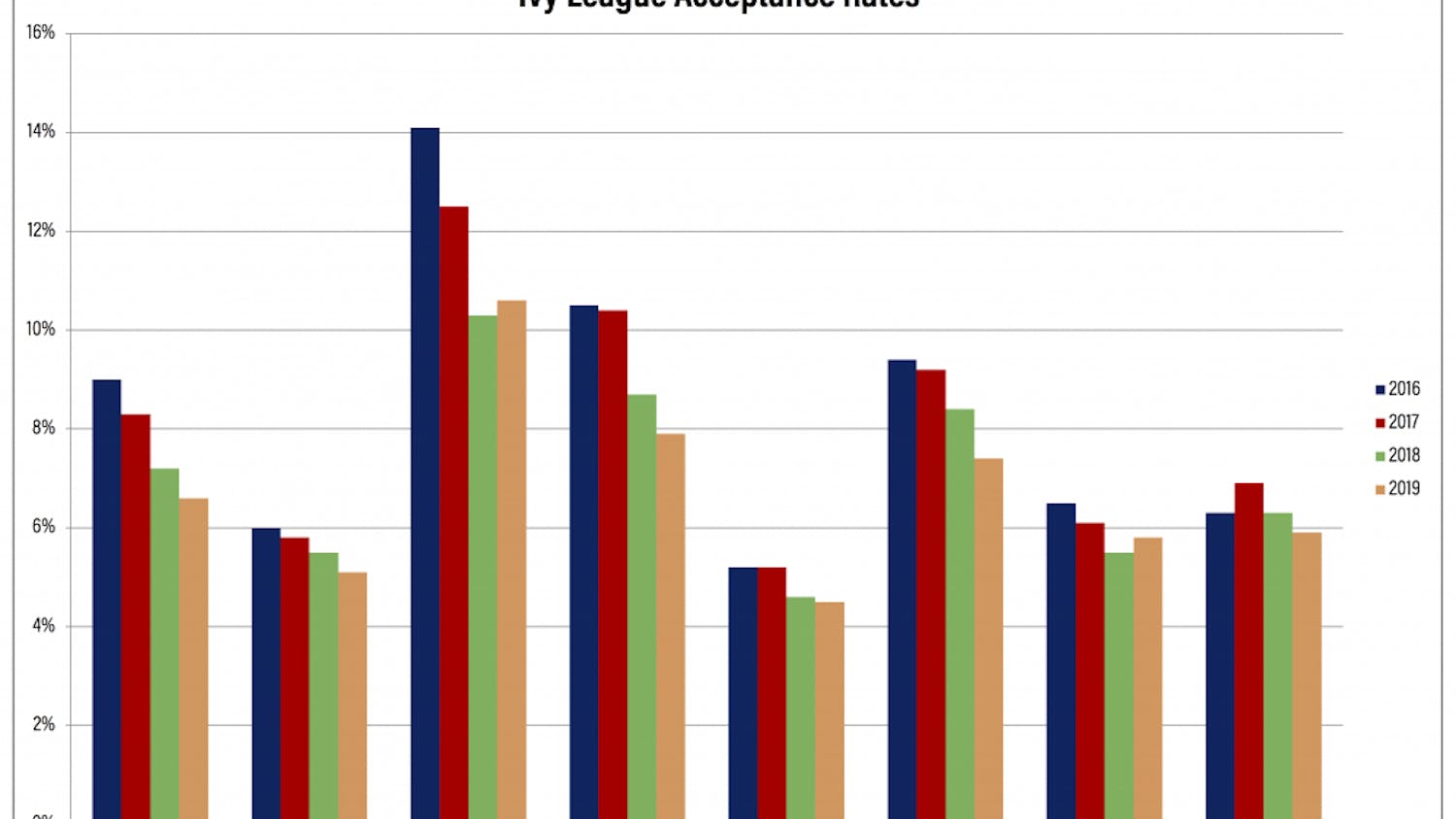

The Upshot, a New York Times blog, published an interactive website displaying the findings of the NBER study that gives us more context to understand how Dartmouth reflects the broader national trends. First, we see the Dartmouth numbers in 2017: 21 percent of students came from the top one percent of household incomes, 69 percent came from the top 20 percent, and just 2.6 percent of students came from families in the bottom 20 percent of household incomes. But five of the other Ivies also had 15 percent or more of their students coming from the top one percent, and all eight schools had a student body where more than 60 percent of families fell in the top 20 percent of American households. Beyond just the Ivies, 38 colleges in the United States had more students from the top one percent than from the entire bottom 60 percent.

The problem is that the NBER study shows that the elite colleges that most prep schools are geared towards are far better at moving students from the bottom income brackets to the top than they are at increasing a wealthy student’s earning potential. So, while those students may be just as eager to learn and challenge themselves, having an elite education dominated by upper-class students is redundant, because those individuals already have access to the resources that would enable that kind of intellectual engagement.

All of this might not be that surprising to anyone, and none of these numbers are intended to shame any of us for being born into lives that enabled us to get here. The point is not that we shouldn’t have had access to the high-level educations that got us into Dartmouth, but that it is dangerous to believe any of us are uniquely deserving of the educations we enjoy today.