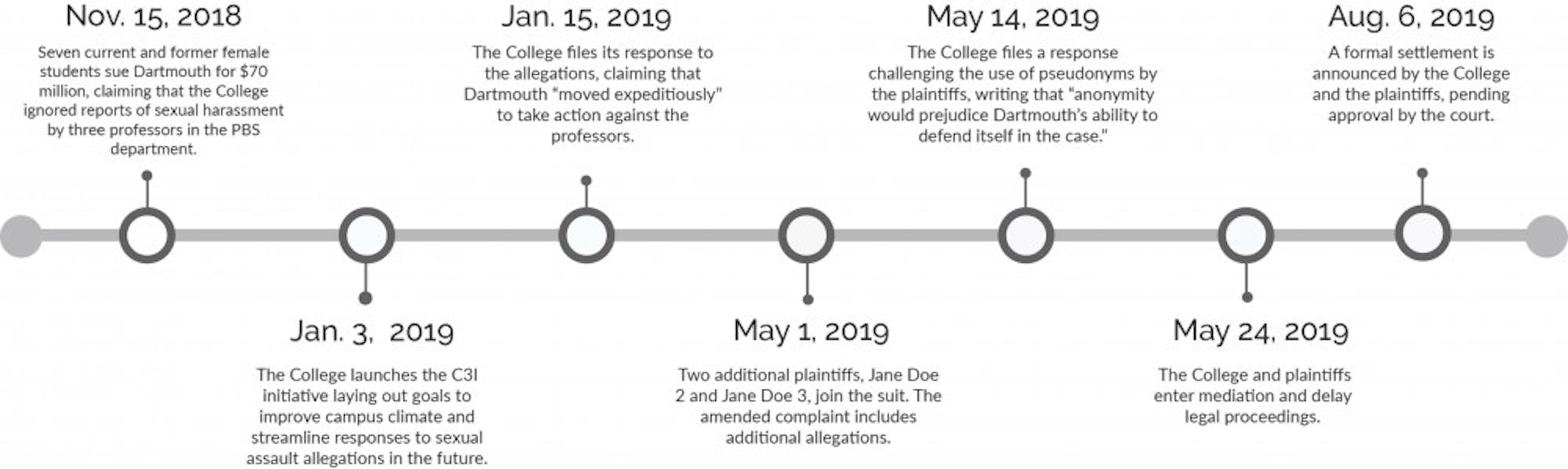

Editor’s note: The class action lawsuit against the College about which this article is written concluded on Aug. 6 with an agreement for settlement. As of press time, the parties have requested a 15-day extension to file the Stipulation and Agreement of Settlement from the original Aug. 20 date. Many of the interviews featured in this article were conducted prior to when the settlement was reached.

Just weeks after the New York Times first reported allegations of sexual misconduct and abuse by Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein, sparking the worldwide #MeToo movement, the Dartmouth community first learned of allegations against three professors in the psychological and brain sciences department.

Reporting from The Dartmouth in Oct. 2017 unveiled the existence of the investigation and that the accused professors had been placed on leave and barred from campus. That November, further reporting revealed the scope of the allegations when 15 students signed a statement alleging the creation of a “hostile academic environment” that included drinking and sexual harassment.

In the summer of 2018, the three accused professors — Todd Heatherton, Bill Kelley and Paul Whalen — all resigned or retired following recommendations for dismissal. Though investigations by multiple law enforcement agencies, including the New Hampshire attorney general’s office, continued, the College’s investigation concluded, bringing what appeared to be an ending to the saga just as the Class of 2022 arrived on campus.

The Rapuano lawsuit

In November 2018, however, the alleged misconduct of these professors was thrust back into the spotlight. Seven women sued Dartmouth, alleging that the departmental culture created by the professors resembled a “21st-century Animal House” and that the College failed in its “duty to protect its students from unwanted sexual harrassment and sexual assault.” Six of the plaintiffs were named in the lawsuit, while one used the pseudonym “Jane Doe.”

The class action suit, which asked for $70 million in damages, garnered national news attention.

Closer to home, the Dartmouth community’s response to the allegations in the plaintiffs’ filing, as well as Dartmouth’s subsequent legal actions, have become part of the broader conversation on campus about sexual misconduct.

The lawsuit alleged that the three professors “leered at, groped, sexted, intoxicated and even raped female students.” It also asserted that the professors, among other suggested abuses, “conducted professional lab meetings at bars, invited students to late-night ‘hot tub parties’ in their personal homes and invited undergraduate students to use real cocaine during classes related to addiction as part of a ‘demonstration.’”

The suit alleged further that Dartmouth “has known about bad behavior by these professors for more than sixteen years,” but that it failed to take action, “thereby ratifying the violent and criminal acts of its professors.”

Diana Whitney ’95, a founding member of the Dartmouth Against Gender Harassment and Sexual Violence group characterized her initial reaction to the allegations in the lawsuit as “shock” and said she felt “appalled.”

“How could this happen at Dartmouth?” Whitney recalled asking. “The allegations … are horrific, and they date back to 2002,” she said.

Itzel Rojas GR ’19, a recent graduate of the experimental and molecular medicine program, said she felt a sense of “sorrowful empathy” for the plaintiffs who were impacted as graduate students, knowing how vulnerable graduate students can be to toxic relationships when it comes to mentorships in graduate school.

In an email to the Dartmouth community on the day the lawsuit was filed, College President Phil Hanlon defended the College, writing that the College’s actions to remove the professors from campus were “unprecedented” and that the investigation into the allegations was “rigorous, thorough and fair.”

The community reacts and responds

A response to the lawsuit emerged first from various groups in the wider Dartmouth community. Some alumni said that they would cease financial support of the College, while others wanted to wait until the College filed a response.

“The thing that’s most factually in dispute is, “Were we [the College] told? And [did the College] fail to act in an appropriate manner and allow this to continue based on a totality of the circumstances?” said Catherine Duwan ’89, a New Jersey lawyer who said she would reserve her judgement until the lawsuit runs its course. “If all of these allegations are true, that’s a horrible failure on the part of the College,” she added.

Whitney and others took action immediately, helping to found the Dartmouth Community Against Gender Harassment and Sexual Violence. The activist organization began organizing online, circulating petitions and creating a statement of support for the seven plaintiffs in the suit.

“Going back to those first few weeks, that was what felt the most important: recognizing how brave these seven women were, current and former Dartmouth students, to have come forward with this lawsuit and these allegations,” Whitney said. She criticized Hanlon’s initial response as “unsatisfying at best” and “collegial but evasive.”

In December, nearly 100 faculty members signed a letter in support of the plaintiffs that was published as a Letter to the Editor in The Dartmouth. The same week, a letter with over 500 student, alumni, faculty, staff and community member signatures was published that condemned “an institutional culture that minimizes and disregards sexual violence and gender harassment.” It called on Dartmouth to “acknowledge their glaring breach of responsibility, issue a public apology, and begin a transparent overhaul of regressive practices” and eventually garnered nearly 800 signatures.

The College launches C3I

On Jan. 2, 2019, DCGHSV delivered a list of demands to Hanlon. It included symbolic actions, such as the removal of past-tense language from communications about the campus culture and the planning of a lecture series on the topic of sexual violence; as well as more concrete changes, such as the hiring of ombudsmen, new educational initiatives for faculty, staff, and students and quarterly reporting requirements for reforms.

The following day, Hanlon announced the Campus Climate and Culture Initiative, abbreviated as C3I, in an email to campus. According to the email, the initiative would create a unified sexual misconduct policy for faculty, staff and students, bring in an independent authority to oversee department-level reviews, expand the Title IX office and require all faculty to undergo new online Title IX training, among other changes. It would also mandate an annual report on a variety of progress indicators.

Hanlon also promised to “commit the resources and energy required to overcome the biases and barriers that women and many others face on our campus.” He also wrote that, when implemented, C3I would ensure that “members of our community can advance their careers in a campus-wide environment that is productive, nurturing, professional, and supportive.”

In a statement in response to the announcement of C3I, DCGHSV praised the independent advisory committee. However, it also asserted that portions of the plan “have vague promise but lack the details and context needed for anyone to assess their potential impact.”

Women’s, gender and sexuality studies professor Giavanna Munafo said that C3I would work in addition to existing initiatives on campus, such as the Student Wellness Center’s creation of a four-year sexual violence prevention curriculum. Nevertheless, she worried C3I would ultimately be “more of the same.”

“I worry about it as a … P-R response to the lawsuit,” Munafo said, but added “If it helps, I’ll be happy.” She emphasized that many people at the College are doing C3I-related work, as well as work that pre-dated C3I.

Dartmouth responds in court

On Jan. 15, Dartmouth filed a response to the allegations in which it claimed the College “moved expeditiously” to investigate and take action against the former professors. The filing asserted that any alleged delays in the Title IX process were due to the anonymity the plaintiffs requested, the thoroughness of the investigation that Dartmouth conducted and the extra steps that must be taken to dismiss a tenured professor.

The response also stressed that “Dartmouth does not speak for, and has no intention of speaking in defense of, the Former Professors.” While it said that Dartmouth has “insufficient evidence to admit or deny” many of the allegations in the lawsuit, it firmly asserted that “relevant personnel” were not aware of any serious misconduct until April 2017 and that anything reported was addressed “promptly.”

“If [College officials] knew and didn’t do anything about it, I would think a legal construction argument could be made that it’s tolerating it,” Duwan said, adding that the College would then be “culpable of violating the law.” She stressed, however, that the public should refrain from making judgements before all the facts of the case are known.

“Don’t jump to conclusions and don’t assail the College based on what individuals did — unless in fact it was the case that [they] knew and [they] didn’t do anything about it, or [they] didn’t do enough about it,” Duwan said.

Whitney, on the other hand, called the College’s response a “horrifying document in its victim-blaming rhetoric.”

“It’s very clear that their legal strategy was to say ‘there were three bad apples, and we got rid of them and there’s nothing else wrong,” Whitney said. “They denied all responsibility; there was no question of this idea of how this could have gone unchecked since 2002, and that somebody must have known or been aware.”

New plaintiffs and anonymity challenge

The next major development in the case occurred on May 1, when two additional plaintiffs joined the class action suit under the pseudonyms “Jane Doe 2” and “Jane Doe 3.” The amended complaint included additional allegations of nonconsensual sex, sexual harassment, coercive behavior and inappropriate sexual relationships on the parts of the three professors. It also alleged that Jane Doe 2, an undergraduate student, left the fields of neuroscience and clinical psychology because of her experiences in the PBS department, while Jane Doe 3, a graduate student and post-doctoral fellow, changed her area of research.

On May 14, the College filed a response challenging the use of pseudonyms by the two new plaintiffs, writing that “anonymity would prejudice Dartmouth’s ability to defend itself in this case” because it would “present unworkable challenges” in determining whether the plaintiffs constitute a class.

This filing, which, if adopted by the Court, would have stripped the three anonymous plaintiffs of their anonymity, also garnered national media attention. The New York Times wrote that the legal strategy runs against “longstanding legal practice intended to protect plaintiffs in sensitive disputes” and noted that Florida A&M University had recently made a similar request in a lawsuit of its own. In the Times article, the College’s vice president of communications Justin Anderson said that Dartmouth supported the rights of women to file anonymously in individual cases, but not in a class action case.

Duwan said that while she personally disagreed with the College’s decision to file such a motion, she speculated that the College was concerned about additional plaintiffs joining the suit anonymously.

Rojas said that the challenge to anonymity seemed like an intimidation tactic, noting that she believed it was “unnecessary and damaging.”

“I can only imagine how it felt for women who had thought they were coming forward with this protection,” Rojas said.

In response, DCGHSV circulated a petition condemning the College’s motion to remove the Jane Does’ anonymity that gathered over 600 signatures, including those of District 5 NH Sen. Martha Hennessey ’76, Congresswoman Annie Kuster ’78 (D-NH) and several presidential candidates, including U.S. senators Kirsten Gillibrand ’88 (D-NY), Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA).

A settlement is reached

On May 24, the plaintiffs and College entered mediation and delayed legal proceedings. On July 29, the judge in the case, Landya McCafferty, granted an extension until August 5. College spokesperson Diana Lawrence told The Dartmouth in a statement after the extension was issued that the College “would much prefer to reach a mutually acceptable conclusion to the case outside of the litigation process.”

On Aug. 6, after approximately one week of mediation, a formal settlement was announced by the plaintiffs and College in a joint press release that hails the agreement, pending approval by the court, as “a historic partnership seeking to enact meaningful change.” It includes damages of $14 million for the plaintiffs and states that the terms of the settlement will be made public.

“Taking on a challenging societal issue in a collaboration such as this reinforces Dartmouth’s mission and values in a powerful way,” Hanlon wrote in an email announcing the settlement to campus.

Hanlon added that the College would “continue to strengthen a culture where — without exception and across disciplines — all members of our community can thrive in a learning environment that reflects a deep understanding of the perspective of survivors and is welcoming, professional, supportive, and productive.”

In a joint motion, the plaintiffs and College requested until Aug. 20 to file the Stipulation and Agreement of Settlement and a schedule for remaining legal filings.

Regarding the decision to enter mediation, Duwan noted that generally people prefer not to go through “protracted legal proceedings.” After the settlement was announced, Duwan said that would allow both parties to “get on with their lives,” particularly the plaintiffs.

She added that the legal process will have made an impact on Dartmouth, giving the College an opportunity to update its procedures.

DCGHSV released a statement in response to the news of the settlement that praised the plaintiffs’ “heroic endeavors.”

“[We] hope that their settlement ushers in a new era of institutional transparency, establishing a platform for the eradication of sexual violence and gender harassment,” the statement said.

DCGHSV also re-emphasized its commitment to “seek meaningful change” and stated that Dartmouth must “take a survivor-centered approach and assume full responsibility for the abuses that occurred in PBS.” The statement listed questions and issues that DCGHSV argued Dartmouth must address, such as “factors that allowed this abuse to develop, go unchecked, and worsen over time;” the impact of abuse on faculty and staff; and the College’s “misguided” legal motion to oppose the plaintiffs’ anonymity.

Duwan cast doubt on the idea that the settlement would address any responsibility on the part of the College, and believes that it will likely “regurgitate” the C3I reforms already in motion.

“It’s going to be designed to put Dartmouth in the best light possible,” she said, adding that it also may not address the accuracy of the allegations in the plaintiffs’ complaint.

Before news of the settlement broke, Whitney indicated that she had mixed feelings about the parties’ decision to enter mediation.

“As an activist and as a survivor of sexual assault, I want these plaintiffs to take the course that is the right course for them,” she said. “In terms of visibility and maximum impact for Dartmouth and even nationally on the issue of sexual assault on campus, on some level, yes, I was hoping for a trial.”

Regardless of the terms of the settlement, some still believe more action needs to be taken by the College. Both Whitney and Munafo believe that the PBS department should be put into receivership, meaning that a non- PBS administrator would chair the department and potentially make changes to how it is run.

Now that the lawsuit is nearly concluded, such a move may be less legally risky. Munafo pointed out that while the lawsuit was pending, appointing a receiver could have been seen as an admission on the part of the College that something was fundamentally wrong at the PBS department.

“If you can’t acknowledge anything is wrong, it’s a roadblock to reform,” she said.

Rojas, Whitney and others also helped to create a website, Dartmouth Speaks, that posts stories, some anonymous, of sexual misconduct at Dartmouth.

“Something we’ve hoped for is, in our roles and in our positions, to be a platform to speak for others when they can’t speak, to give a safe space for people to speak comfortably and safely and to provide a space where others can read, reflect, and either learn about their own behavior or find that they’re not alone in their experiences,” Rojas said.

For Whitney, that openness is important.

“I’m so glad that people are actively talking about this and speaking out about it, because that will be how something changes,” she said.

The attorneys for the plaintiffs in the suit declined to comment for this article. The attorneys for the College did not reply to requests for comment.

This article is a part of the 2019 Freshman Issue.