Academia has historically been a white and male sphere. According to the National Center for Education, in 2016, 53 percent of full time professors were white males, while another 27 percent were white females. Despite an increasingly diverse student body, Dartmouth’s own campus reflects these national trends. According to the Office of Institutional Research, 80 percent of the 316 tenured professors at the College in 2018 were white and 62 percent were men. By contrast, nearly half of the newly-admitted Class of 2023 are Americans of color and 12 percent are international citizens, according to the College Admissions Office.

Across the nation, students and experts alike are discussing why it might be important to have faculty members that reflect the diversity of the student body. In the Dartmouth community, many expressed frustration at the College’s lack of faculty diversity when Asian American female professor Aimee Bahng was denied tenure in 2016. Almost 4,000 people signed a petition calling for College President Phil Hanlon to reconsider this decision. From opinion pieces in newspapers to conversations among experts and articles in education journals, many voiced concerns that a lack of faculty diversity may limit the perspectives and conversations in the classroom and can cause minority and female students to feel that they do not have mentors they can rely on.

Dartmouth’s faculty is moving toward more diversity — white faculty members decreased from 87.8 percent in 2017 to 80 percent in 2018 and male faculty decreased from 74.3 percent in 2017 to 62 percent in 2018. Vice president for institutional diversity and equity Evelynn Ellis said that while she believes this change over the last two years represents some progress, the percentage of non-white tenured professors is still too low. She added, however, that Dartmouth’s percentages are roughly similar to that of its peer institutions.

In 2017, 79.9 percent of Harvard University’s tenured professors were white and 74.7 percent were male. That same year, 81.2 percent of Yale University’s tenured professors were white and 74.5 percent were male. The tenured faculty at Brown University, Cornell University, Duke University and Stanford University also had similar percentages of white and minority professors.

Ellis said her office is constantly working with the College’s administration to ensure all parties “buy in” to the conversation regarding the critical need for a diverse faculty. She added that since she began working at the College over a decade ago, there has been much progress in the conversations about diversity her office is having with the College’s administration.

“Our discussions are so much futher along than when I started here,” Ellis said. “What’s happening is a culture shift, which is what you need.”

She said she is optimistic about the future of diversity at Dartmouth.

“If all the mechanisms we are trying to put in place now stick over the next three to five years, I think [the faculty makeup is] going to look drastically different,” Ellis said.

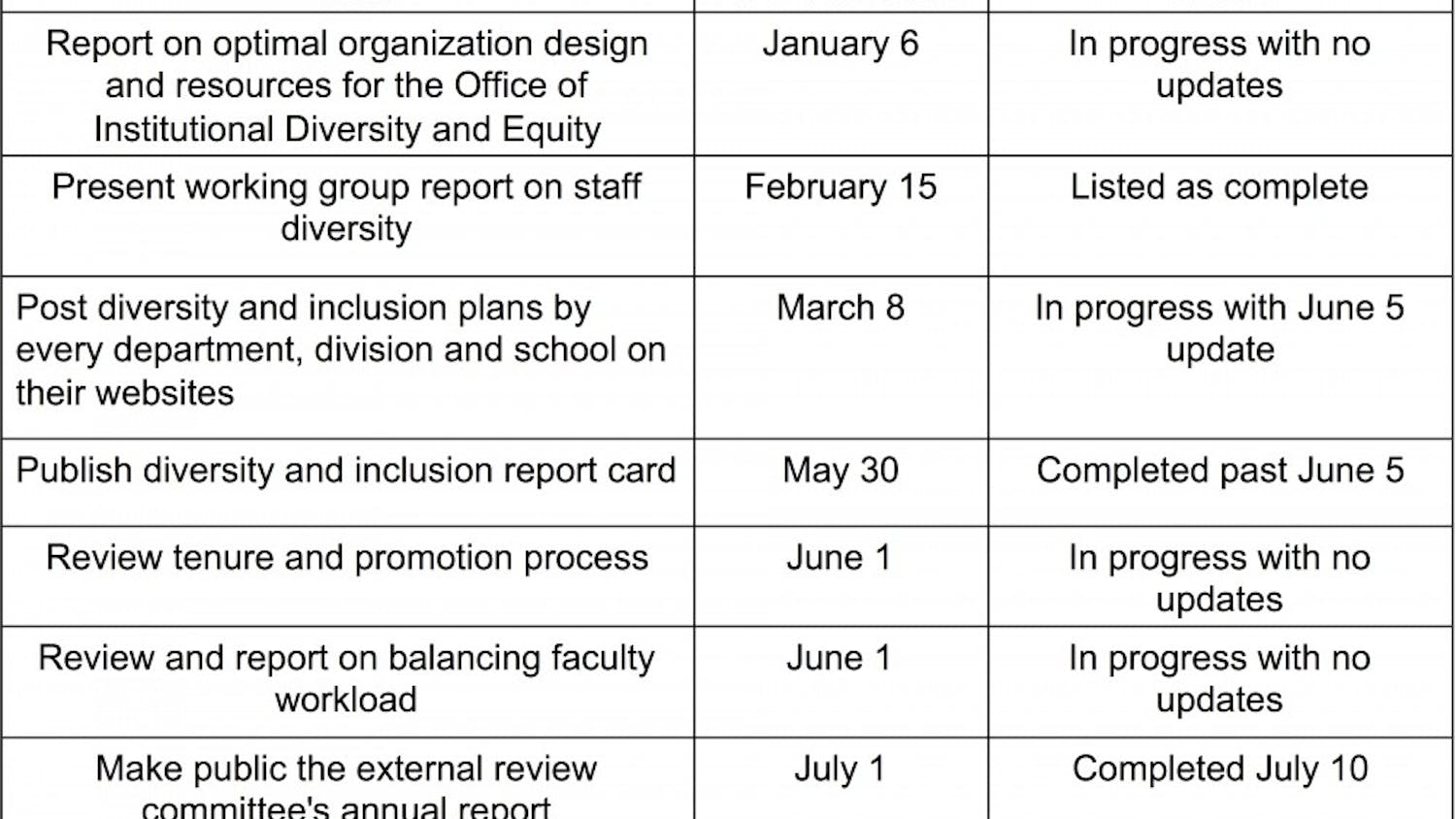

To formally prioritize diversifying the College’s faculty, Ellis and her office joined the administration in launching the Inclusive Excellence Action Plan in 2016, an initiative with the broader goal of supporting diversity at the College through the creation of a more inclusive environment. While the IE action plan was crafted to tackle problems of exclusion more widely on campus. One goal was achieving a faculty of 25 percent minority faculty, according to special assistant to the president Christianne Hardy, who said she believed it was possible to reach the goal by 2027.

According to Hardy, the IE action plan includes funding to support diversity hires and help increase the number of diverse scholars in the path to tenured professorship. The plan also includes the review of all hiring, promotion and tenure processes for bias against minority candidates.

Hardy said she believes these efforts are beginning to pay off. In the three years since the IE action plan was launched, the percentage of minority faculty institution-wide has increased from 17 percent to 19 percent, and 20 percent within the Arts and Sciences division.

“We are making progress. This is, however, a long game,” Hardy wrote. She said a natural turnover rate of about 5 percent of faculty each year both allowed diversity in hiring each year, and risked losing diverse faculty members.

Aparna Parikh, the 2018-2020 Andrew W. Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellow with the Leslie Center for the Humanities, said that in her experience, post-doctoral fellows add significantly to the diversity in their departments, adding that many of the courses tackling subject matter surrounding diversity are taught by post-docs.

In the past year, Parikh has taught two courses in the geography department, one course on gender and development that had been taught before at the College, though not recently, and GEOG 80.06, “Women in Asian Cities.”

In addition to adding diversity to course material, Marianna Peñaloza ’22 said that she and other minority students often find themselves looking to professors of color and female professors for guidance.

“It would be really difficult to navigate [Dartmouth] as a first-generation, minority student if I did not have this mentorship,” Peñaloza said.

Parikh said she has acted as a mentor for a number of students and has served on a number of panels in the past year on the subject of diversity and inclusion.

Racial and gender percentages, however, only represent some of the ways to measure the diversity of Dartmouth’s teaching staff, according to Parikh, who emphasized that some elements of diversity — such as first-generation status, class, sexuality or ability — are often less visible.

“It is a complicated landscape when one is talking about diversity,” Parikh said. “It is also something that is not just a question of who I am, but of what kinds of things I think about in my research.”

Another less visible element of diversity is diversity of thought. Government professor Lucas Swaine wrote in an email that the College benefits from a diversity of and respect for various political attitudes.

He said that although he can’t speak to other departments, faculty in the government department have a broad range of outlooks and approaches.

“There must remain space for healthy disagreement and questioning, and it is crucial to value and protect freedoms of speech, thought, and association, all of which promote political diversity,” he wrote.

International student and history major Janel Perez ’22 agreed with Peñaloza that a lack of diversity amongst professors is reflected in the courses taught at the College.

She wrote that she thinks diversity in the history department is best summed up by the department’s divisions: the U.S., Europe, AALAC (Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean). Perez said such divisions — and the grouping of the AALAC category — made it easy to understand the U.S. and euro-centric strengths of the department. She said that the department could hire more faculty in the AALAC division in order to allow each section to stand on its own.

Perez noted, however, that she loved how responsive the history department is, and wrote that the faculty has a “healthy diversity of gender and race (at least considering how small the department is).” She also said that history is “inherently a dynamic discipline,” so narratives and interpretations are constantly evolving.

Although Perez mentioned that she sees room for improvement, she also said she has been impressed by the fast action taken by the history department heads to resolve issues of diversity raised by students. She explained the major is undergoing changes following department-held student focus groups, in which the issue of faculty diversity was raised.

Ellis said her office recognizes that one of the most important issues related to diverse faculty is faculty retention. Her office focuses much of their efforts on supporting new faculty and fellows and said she encourages the College’s perennial faculty to do the same.

Ellis said she believes that the academic environment must be welcoming and that once someone is hired, there needs to be a plan in place to support them.

According to Hardy, the College has instituted a mentoring program that pairs female faculty members and faculty of color with mentors to serve as resources during their years as junior faculty. Hardy said the mentorship program is not formally named, but that department chairs are asked to encourage senior faculty to mentor junior faculty. Associate deans meet with all junior faculty to aid in pairing mentors and mentees as needed, either within the same department or across departments and schools. She also said that the Employee Resource Networks run by IDE helps faculty and staff transition to living in the Upper Valley, including for Black, Asian, LGBTQIA+, Latinx and female employees.

Ellis said that there are some people who end up working in completely different professions who would have made great professors because the environment of academia may not be conducive to retaining those not traditionally represented.

“Once professors are in [academia], they need to know they can move up in the workplace regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, ability,” Ellis said. “If they believe the playing field is not level … they aren’t going to come into [academia] because they don’t have to. They have options.”

This article is a part of the 2019 Freshman Issue.