Most students can remember the first time they stepped foot on Dartmouth’s campus. Perhaps they were struck by the red brick and white columns of the dorms, or the impressive outline of Baker tower puncturing the blue sky. Or maybe it was the stately white of Dartmouth Hall, framed on either side by Thornton and Wentworth Halls.

Many of these first impressions of Dartmouth involve the College’s architecture, which has come together as the result of decades of College history.

Dartmouth was one of nine colleges founded in what became the United States prior to the Revolutionary War, and because it came to being in the late 18th century, there are several references to the colonial era in its architecture. The colonial origins of the College account for a certain harmony that permeates the campus — surrounding buildings are wrapped in red brick and trimmed with white, with windows peeping out between green shutters, according to art history professor Marlene Heck.

Heck, who specializes in the history of architecture, said that while parts of campus were built at different points in time, the same materials and stylistic choices connect the buildings into a cohesive whole.

The distinctive “look” of Dartmouth’s campus nonetheless includes the necessary variety that allows students to continue to discover their surroundings in new, unconventional ways, studio art professor Zenovia Toloudi wrote in an email to The Dartmouth.

“This variety is crucial to break homogeneity … and to also help us develop some special connection with particular ‘corners’ on campus, to find a spot, a space that feels [like] home,’’ Toloudi wrote.

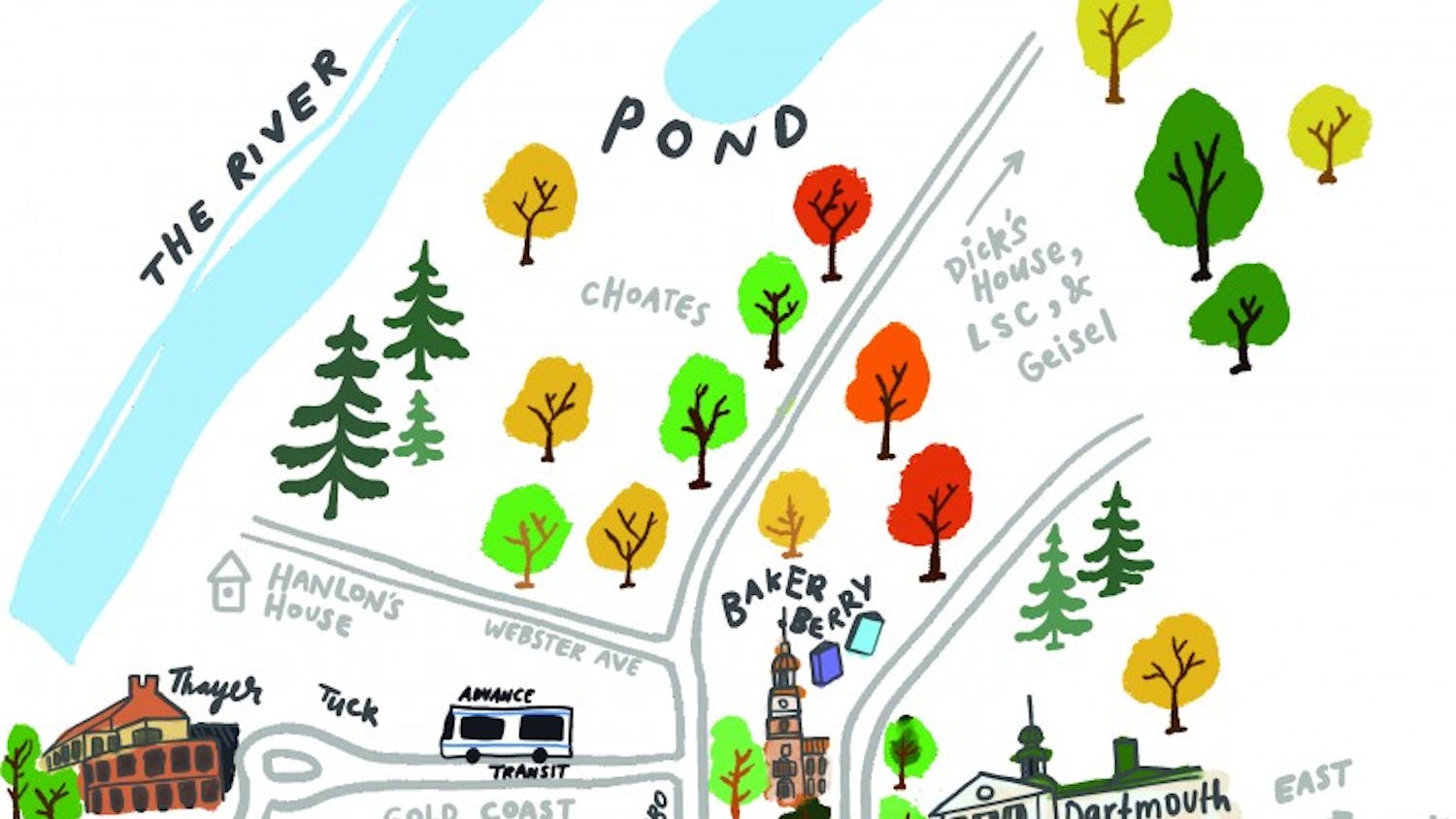

Dartmouth’s campus cannot be separated from its location in rural New Hampshire, with its open spaces and natural setting integral to the school’s identity. The Bema and the Connecticut River are a mere minute’s walk away for students seeking respite outside. The Green also represents a unique facet of the campus; Dartmouth is one of few college campuses where the town and college merge together in the middle.

Eleazar Wheelock’s home, located where Thornton and Reed Halls now stand, was the first building on campus. Dartmouth Hall was built beside it as the first permanent academic building, and the College consisted only of Dartmouth Hall until the early 1820s when Wentworth and Thornton Halls were built, followed by Reed Hall in the 1830s. These buildings were designed in what is referred to as the Georgian style, which originated in English-speaking countries between 1714 and 1830 and was inspired by the symmetry and proportion of classical Greek and Roman architecture. The architectural style features minimal ornamentation on the exterior of buildings and adapts classical influences to smaller, more modest buildings, Heck said.

In the 1920s, Dartmouth’s campus underwent a major expansion, and most new buildings were built in Georgian Revival style. The Gold Coast dorms went up, the Tuck School of Business was relocated and the iconic Baker Library was built, along with Sanborn House, Carpenter Hall, Silsby Hall, Butterfield Hall and Russell Sage Hall.

Many buildings on campus have previously had different identities. Until 1930, for example, McNutt Hall, which now houses the admissions and financial aid offices, housed Tuck. The Collis Center was known as College Hall until 1993, and Webster Hall was redesigned to accommodate Rauner Special Collections Library in 1998.

Along with changes and additions, Dartmouth’s campus has also seen demolitions. According to Heck, two buildings known as Gerry and Bradley Halls were torn down in the early 1960s in the current location of Haldemen and Kemeny. The late 1950s and early 1960s were a period of modernity for Dartmouth’s architecture, as Dartmouth’s president at the time, John Sloan Dickey, wanted the school to shed its small college character — Gerry and Bradley, as well as the Hopkins Center for the Arts, Leverone Fieldhouse and the Thompson Arena, were all part of Dickey’s efforts to revamp Dartmouth’s rural character with modern architecture.

Dartmouth’s architectural development took place in spurts in accordance with campus needs. However, with the time that has passed in between each construction period, architectural tastes have changed and building campaigns have naturally featured different styles, according to Heck.

“After all, you wouldn’t want to build anything that looks like Rollins Chapel in the earliest 20th century,” she said.

Michael Lin / The Dartmouth Senior Staff

The Haldeman Center, Kemeny Hall and the McLaughlin Cluster were all designed by Moore Ruble Yudell, an architecture and planning firm, in the early 2000s. The designers looked at the space north of Baker-Berry and formulated a master plan that looked at the district of the campus as a whole and how it would expand.

Jeanne Chen, principal architect of the team of design architects for the three projects, took a holistic approach to designing for the campus. Chen said it was crucial to the team to not only respect the “language,” or style of pre-existing buildings, but more importantly to respect the natural environment of the college that forms Dartmouth’s character. The team hoped the new expansions would unify the campus and create a stronger sense of connection and inclusion. McLaughlin, Kemeny and Haldemen were purposefully built to feel accessible and welcome, aided by the sweeping glass windows that were intended to open up the buildings, Chen added.

One of the greatest challenges when approaching construction of the McLaughlin dorms and other new buildings was meeting the demand for a large building space while simultaneously creating an inviting and inclusive space, Chen said. To approach this obstacle, Moore Ruble Yudell took a big building and broke it down into smaller series of forms. The separate buildings are linked by grassy, white elements and are brought together with a commons in the middle to draw the community together.

“One of the things that works the least well is if you take this Georgian style and take this big building style and don’t respect the spirit and history of the campus,” Chen said. “It becomes more of a wallpaper because it doesn’t capture the essence of the project.”

Kemeny, meanwhile, is “L-shaped” to frame the back of the library, to not only reinforce the historic campus but also simultaneously convey modernity and fulfill the need for social spaces.

“That’s what we think makes a project rich and responsive — it’s not just about the language but it’s about asking if it is welcoming, and does it make the other buildings better,” Chen said.

The obvious answer to creating visual harmony on an existing campus is to simply imitate the style of previous buildings, Chen said, but noted that capturing the “spirit” of the other buildings is often more important than copying their look exactly.

Dartmouth is presently going through a significant construction spurt, including the recently renovated Hood Museum of Art and Black Family Visual Arts Center. A new Center for Engineering and Computer Science is currently being built that will house the Magnuson Center for Entrepreneurship and Electron Microscope Facility, and additions are being made to buildings at the Thayer School of Engineering. The new Arthur L. Irving Institute for Energy and Society will be located between Tuck and Thayer, and a new dorm is also underway where House Center A currently stands. While the buildings will not copy the Georgian revival style, they will incorporate red brick and reference stylistic elements of the era.

Heck said that, in her opinion, new buildings should reflect the era of their construction.

“I think that [new] buildings need to speak of their time,” Heck said. “A building that’s put up in 2020 in Dartmouth shouldn’t look like an earlier building or a copy of an earlier historical style, but in a way that it relates to buildings around it. It should speak to good design as something that contributes to the campus but, it should also be a good neighbor to all of the buildings that came before it.”

Campus architecture at the College is often a contentious issue with students, as many students dislike the modern aesthetic of newer buildings such as the Hop or the Choates.

Heck noted, however, that every building on campus is a record of a moment in the College’s past and “what the College wanted to say about itself at a certain moment in its history.”

She said that she believed tearing down buildings for the sake of visual continuity is an unnecessary rewrite of Dartmouth’s history.

“Not everything is worthy of being preserved in its entirety,” Heck said. “But keeping something that was a part of what we’ve pulled down or changed as a record of a certain moment in our history is important, because the ’23s will come in, and they won’t know that there’s been a lot of change lately. This is their Dartmouth.

This article is a part of the 2019 Freshman Issue.