By the Aegis’s account, Students for a Democratic Society never existed at Dartmouth. Student newspapers and oral histories identify 1969 through 1971 as the period of peak activity for the anti-Vietnam War activist organization, but Dartmouth’s yearbooks from these years do not once mention SDS.

It is unclear whether this omission was a political statement on the part of the Aegis staff, an oversight, or a reflection of the relative irrelevance of SDS to the average Dartmouth student. Ironically, the Reserve Officer Training Corps — the organization that SDS sought to abolish — received multi-page spreads.

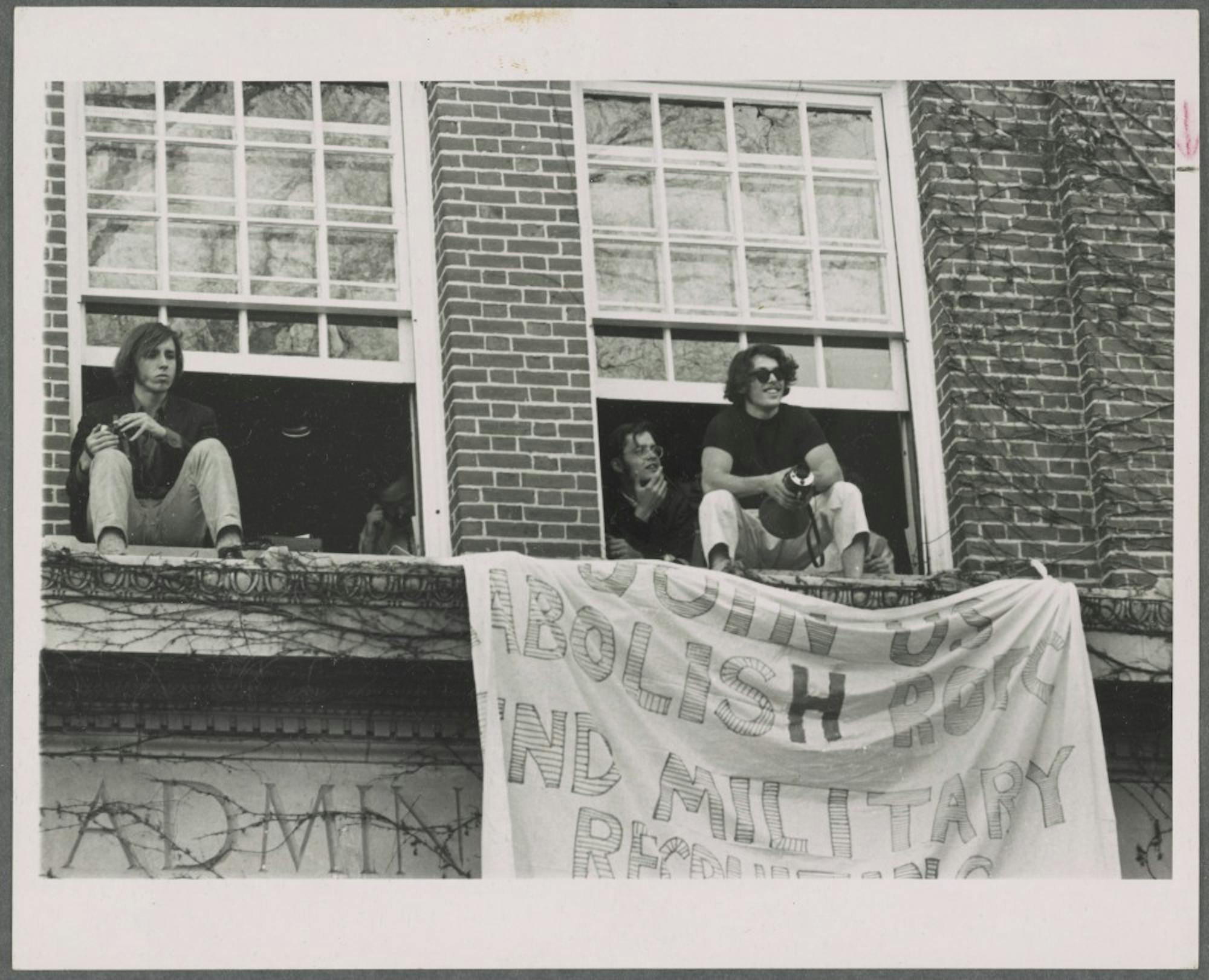

Student organizing in protest of the Vietnam war is instead represented by a handful of photographs presented without context. A spread of headlines from The Dartmouth, a boy speaking before a crowd with hands clasped behind his back, and President John Kemeny holding a lemon above his head like a raised fist — these serve as poor proxies for peace lines on the Green, teach-ins at the Top of the Hop, criticism of then-President Kemeny for his partiality to student protestors and other happenings that, to those involved, felt as important as life itself.

When the present feels all-consuming and the past feels small and sepia, it is tempting to question why we should care about what happened here half a century ago. But according to history professor and Dartmouth Vietnam Project director Edward Miller, “understanding the views of particular constituencies and groups of the broader Dartmouth community requires looking at history.”

In preserving oral histories, as DVP did for Dartmouth in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and in speaking with those who lived through key historical moments, as I did in interviewing David Aylward ’71 for this article, we might discover something about the present.

This particular history takes place during a time in which Rauner Special Collections Library was a performance space, the Collis Center was “College Hall” and ROTC was as established and visible an institution as the football team.

“Most Dartmouth students knew and expected that if they were U.S. citizens, they owed a certain amount of military service; therefore, ROTC became a very common and normal part of the college experience,” Miller said.

According to Aylward, “military trainers were given professor status, and [ROTC] courses got credit … [ROTC] was fully part of the curriculum.”

Aylward described Dartmouth’s administration and student body as largely “white, male, athletic [and] upper-middle class,” though the world outside was far less clear-cut. In 1965, Aylward’s junior year of high school, President Lyndon Johnson “drastically escalated the number of troops in Vietnam … and draft calls went way up,” he said, citing this moment as the beginning of his awareness that the Vietnam War was something to which he needed to pay attention.

Aylward parses his thinking about the war into a “public policy track” and a “personal track.” He might contemplate how, from a war strategy perspective, the United States might approach the Vietnam War, but such ponderings were eclipsed by a more immediately pressing question: How can I not die at war? There are a variety of answers to this question, and even 50 years later, Aylward is able to rattle them off with ease.

In the face of a war that they considered to be a personal threat, “young people were in revolt against the society, and against this set of policies, and in revolt against their parents, who represented that,” Aylward said.

Paul Hodes ’72, whose story was recorded by DVP, agreed. He said he “quickly saw [himself] as an outsider in a conservative system, [in] the school and the government and the country.”

As a self-proclaimed activist in a community that he found conservative and monolithic, Aylward was distinctly aware of the fact that he “stuck out.” But he wasn’t the only activist at the College. A group of “peaceniks” had been protesting the war in the year or two before he arrived at Dartmouth. They would stand in a shoulder-to-shoulder across the path from what is now Collis to Dartmouth Hall every Wednesday at noon.

Around this time, the Dartmouth chapter of Students for a Democratic Society was formed. According to Aylward, their demands were an end to campus visits from army recruiters and the elimination of the Dartmouth chapter of the ROTC. These were the manifestations of war that he said were “closest to home” for students.

There is no clear-cut tale to tell of what happened after that. The phrase “objective history” is somewhat oxymoronic — history is a fragmented collection of the thoughts of those who experienced it. Hodes’ and Aylward’s retellings of what happened are as different as they are similar. Were I to gather all the accounts of student activism at Dartmouth during the Vietnam War era, I’m certain I would end up with a prismatic Venn diagram of congruencies, contradictions, caricatures and colors. But I only have two students’ stories as recalled 50 years later. Take what follows with a grain of salt.

One prominent feature of both Hodes’ and Aylward’s histories is a sense of urgency.

“We felt individually threatened,” Aylward said. “The country and government we were trained to believe in turned out to be not what it was.” For Hodes, too, “it all felt dangerous and exciting.” But while Aylward retold the events of those years with fervor and excitement, Hodes’ account was colored by an undertext of regret.

“I guess there were some [SDS] meetings and discussions about, you know, what to do, and there were some crazy schemes that were rejected,” Hodes said. “It wasn’t necessarily effective or mature.”

Despite this reticence to endorse SDS undertakings and his insistence that his affiliation with the organization was “loose,” Hodes was undeniably involved. During the 1969 SDS takeover of Parkhurst Hall, he was entrusted with a bullhorn and the responsibility of alerting the protestors of police presence.

In contrast, it was with reverence and pride that Aylward recounted the “genius” of the idea to publicly fast in protest of the war, the “radical change” he saw in his fellow students as the anti-war position became more widely accepted, the pervasive “sense of urgency” and even his fear that he would be expelled from school for his involvement with the Parkhurst takeover.

Hodes remembers “feeling like [he] was at the Alamo … It was like it was the hardy, small band of virtuous people about to be crushed.” But he also remembers the fear and paranoia evoked by the possibility of expulsion, by the Kent State shootings and by the loss of multiple friends to LSD overdoses.

He had a friend who was in Navy ROTC and was a cheerleader on the football team — activities that to him “represent the historical tradition of a conservative Ivy League school.” After his first acid trip, that friend became an “orange-robed, shaved-head Hare Krishna.” This rapid, almost violent transition, rattled Hodes.

“I lost track of him,” he said. “The next time I saw him, he was panhandling in front of the [Hopkins Center] in orange robes.”

Fear is what killed SDS’s momentum, according to Hodes. Aylward has a different account of SDS’s final days. For him, it was over because they had won.

By the end of the movement, there was no need for the movement: The College ended its relationship with ROTC, military recruitment stopped and most students shared SDS’s anti-war perspective. Further, President John Sloane Dickey — whom Aylward described as “an old school, State Department-trained, cold warrior type” — stepped down. He was replaced by Kemeny, who was far more receptive to SDS’s demands.

“I remember going to Kemeny and saying, ‘We’re going to close the school down tomorrow, we’re going on strike,’ and him saying, ‘Beat you to it,’” Aylward said.

During Green Key weekend of 1970, there was a concert by the Young Bloods in Leverone Field House. Aylward distinctly remembers the following moment, which for him symbolized the profound unity that characterized SDS’s last days.

“Kemeny had taken all kinds of s— from alumni and from the Manchester Union Leader. The Union Leader had attacked him for being a lemon. And he stood up in front of the crowd with a lemon in his hand. The place went nuts, absolutely nuts. At a time when you had students getting their heads cracked in Jackson State Mississippi, at Dartmouth, everyone was together.”

So which account is true? Did SDS fizzle out because it had finally succeeded in uniting the Dartmouth student body and administration? Or did SDS dissolve in a cocktail of paranoia and bad acid trips?

I don’t think it has to be an either-or question. There’s truth in both stories. And in this case, I don’t believe that tweezing the truth from memories will yield any significant insights. The experiences of both Aylward and Hodes are valid, and they both have something to contribute to a modern understanding of these events.

One thing that struck me as I listened to their stories is how much has remained the same, even in the midst of so much change. It’s difficult to ignore the parallels between students’ revolts against ROTC then and criticisms of the Greek system now. And in listening to Hodes’ account of his struggle to understand his father’s apathy towards military violence, I heard echoes of discussions about sexual assault that I’ve had with my family members. It was like examining a text with a magnifying glass only to realize that I was holding a mirror.

I wish I could offer up profound insights on history and activism and campus politics, but frankly, I think the only thing I have to contribute is a lyric from a Corrine Bailey Rae song: “The more things seem to change, the more they stay the same.” Fittingly, she didn’t come up with that on her own, either. It’s a translation of an epigram by French novelist Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, written in the middle of the 19th century.

Things really do stay the same.

Correction appended (May 21, 2019): The original version of this article stated that the campuswide strike occurred during the spring of 1971; however, it actually took place during the spring of 1970. The article has been updated to reflect this change.