From the outside, academic departments may seem like established, unshakable institutions. It is easy to take them for granted, to view them as givens. But behind the clear-cut acronyms, they are constantly evolving.

In creating a department, a college or university effectively endorses a field of study. Academia decides what knowledge is worthy of exploration and what skills the next wave of workers will possess, all in the context of an ever-changing world and a half-formed future. Every body of higher education has a different collection of course offerings, and those differences reflect behind-the-scenes — and oftentimes political — conversations held by the faculty and the administration.

Take, for example, the recent elimination of the Asian and Middle Eastern studies department and the department of Asian and Middle Eastern language and literatures, and the subsequent creation of the Middle Eastern studies program and the Asian societies, cultures and languages program. This change could be construed as a move away from a more reductionist approach to studying Eastern cultures, or as a response to current political realities in the international arena.

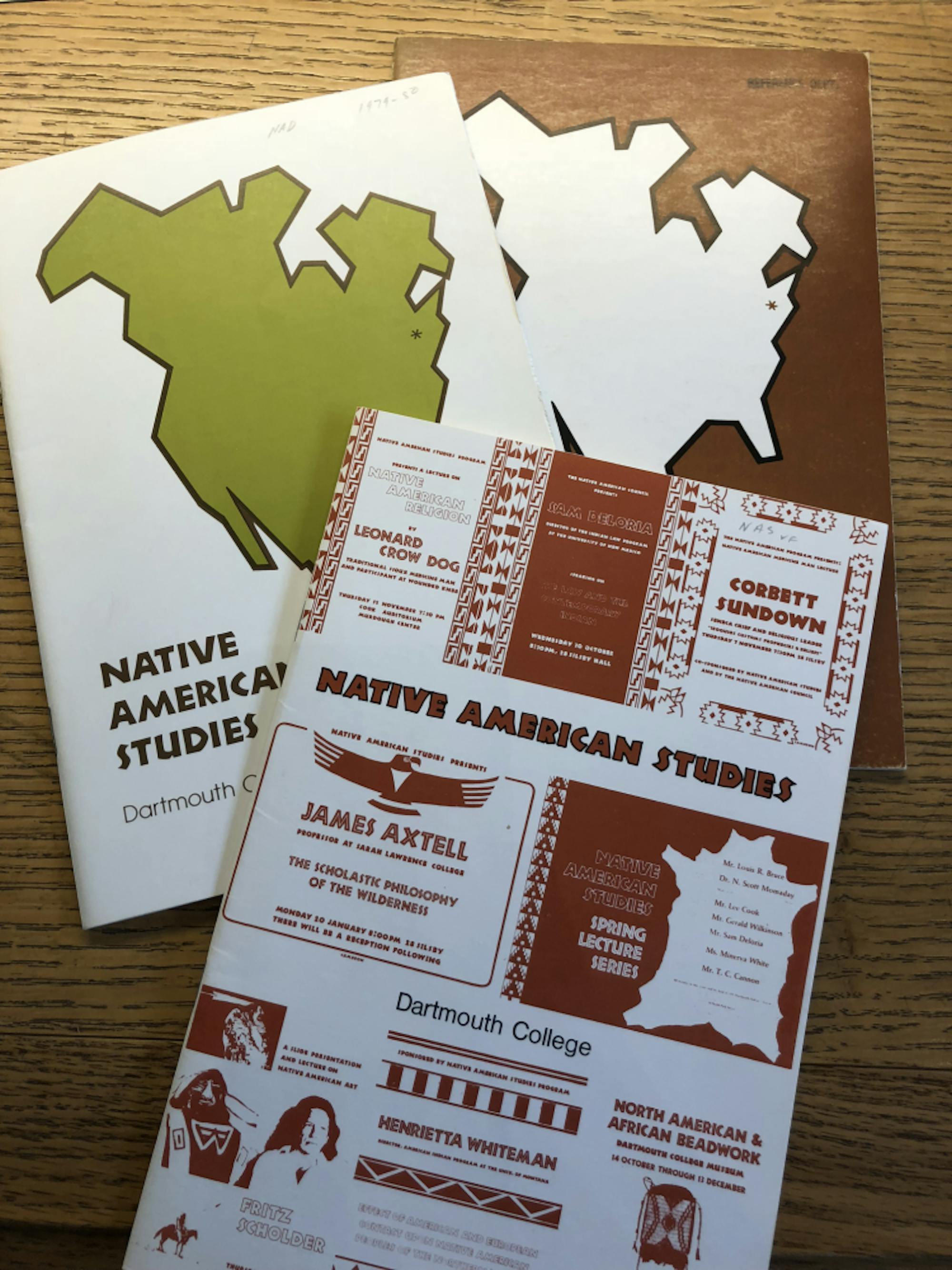

It would not be the first time that changing political norms influenced academic departments at Dartmouth. The College’s 40-year-old program in Native American studies is renowned amongst its Ivy-League peers. NAS was formed in 1972 under the leadership of then-College president John Kemeny. Its creation was part of a broader effort to diversify the College and to renew its commitment to its original mission of “educat[ing] and instruct[ing] ... Youth of the Indian Tribes in the Land … and also of English Youth and any others.”

The move came in the midst of intense pressure from Dartmouth students and other advocates to end the College’s use of a caricaturized Native American as its mascot, and it served as a public, almost symbolic, signal of the College’s values and priorities. In 1968, a group of four Native American students — the only four enrolled at the time — succeeded in convincing Dartmouth’s athletic council to ban the decades-old tradition of having a male cheerleader-mascot dressed as a Native American at football games, arguing that it was both insulting and ironic given the College’s original mission of educating Native Americans.

In 1974, the Board of Trustees officially declared the Native American mascot to be “inconsistent with present institutional and academic objectives of the College in advancing Native American education,” a likely reference to the newly-minted NAS program.

Initially, students pursuing Native American Studies could only modify majors in other departments or pursue coursework “certificates,” and the department itself was only made permanent after eight years. The example of NAS illustrates the paradox inherent to creating or changing academic departments. Institutions of higher education, though they are inherently bureaucratic and slow-moving, must be responsive to changing technology and changing cultural norms.

The creation and continued evolution of the computer science department further exemplifies this phenomenon. According to computer science professor Thomas Cormen, though computer science became a well-defined academic field in the late 1950s, Dartmouth did not employ a computer scientist until 1972 and did not graduate a computer science major until 1979.

This lag in institutionalized programming, however, did not prevent the College from involving students in the burgeoning field of computer science on a more ad-hoc basis. “In the early 1960s, [Dartmouth] actually had a lot of undergraduates doing serious programming,” Cormen said. “We didn’t really offer that many classes, but what we did do was get people involved in the real stuff. We had students writing the systems software.”

In fact, BASIC — a streamlined coding language — and the Dartmouth Time Sharing System — which allows computers to run multiple jobs at a time—were both developed at Dartmouth in the early 1960s. Students were heavily involved with both projects, according to Cormen.

Around this time, Dartmouth began offering two computing courses, both of which were housed in the mathematics department. In 1984, the math department was rebranded as the “department of mathematics and computer science,” and computer science courses were officially noted as such in the Office of the Registrar catalog, Cormen said. He added that these changes served as a formal recognition that computer science was a worthy academic pursuit in its own right.

New academic departments spawn from existing departments more often than they emerge from nothingness, as did the Native American studies department. This is particularly true of the field of computer science.

“If you look historically at computer science, you’ll see that in some places it comes out of math departments. In other places, it came out of electronic engineering,” Cormen explained.

In some places—such as Cormen’s alma-mater the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—computer science still exists as a subunit of a larger department. At Dartmouth, however, a 1993 programmatic external review recommended that the math and computer science department split. In 1994, it did.

It has since grown tremendously, though this growth has not been seamless. The inaugural year of the department, its chair Donald Johnson died unexpectedly of a heart attack, leaving a leadership vacuum that forced “a lot of responsibility on untenured faculty,” Cormen said, describing the department’s early years as “a pretty rough go.” He also recognized the dot-com boom in the late 1990s, and subsequent dot-com crash in 2000, as challenges for the young department.

Now, however, computer science is thriving at Dartmouth. According to Cormen, last year the department graduated 100 majors. Forty-one computer science courses are being offered this fall. And, once a sub-discipline itself, the computer science department has expanded to the point that it now houses its own specialty branch: digital arts.

The digital arts minor program was founded in 2007 by computer science research associate professor Lorie Loeb, who now co-directs the program. The minor explores the intersection between technology and the arts, with a “firm foundation in aesthetics,” Loeb said.

At the time, Loeb was teaching computer animation classes. She noted strong student demand for “3D-modeling and animation courses,” and when another professor interested in graphics joined the computer science department in 2006, she felt she had enough student and faculty interest to defend her pitch for a new program of study.

She faced resistance from faculty members worried about “how this might impact their enrollments or their program,” she said. There was also some concern that a digital arts minor would be too pre-professional and at-odds with Dartmouth’s liberal arts tradition. According to Cormen, computer science faculty addressed this concern by stressing the would-be department’s commitment to the intellectual basis of computer science, beyond its practical applications in the workforce.

Since its inception, the digital arts program has thrived, attracting more students and more faculty. It now offers a masters degree, and Loeb hopes that in the future it will work with other departments to form a major program. She feels that the establishment of the minor was integral to the program’s development because it created a cohort of students pursuing a common academic interest, effectively building comradery and collaboration.

“We want there to be a community amongst students who have gone through the program, that they have a certain set of skills and a culminating experience to pull it all together,” she said.

The minor also “allows [students] to take the courses and get credit for it” on their resumes, she added. She believes this incentive directly resulted in increased student interest. Programs can further benefit from having their own departments, said Cormen, who joined Dartmouth’s computer science faculty shortly before the program moved to a separate department.

“Since we’ve become a separate department, we’ve never had a tenure case fail,” he said, referring to the process through which faculty members in a given department petition for tenure. “Before we became a separate department from math, we hardly ever had a tenure case succeed … There were only two.”

He attributes this discrepancy to the fact that faculty members’ tenure cases are now reviewed by fellow computer scientists who truly understand the field. For similar reasons, he has found curricular reviews and adjustments to be simpler and more effective post-switch.

The department’s impending move to the soon-to-be expanded facilities of the Thayer School of Engineering is another example of the perks which come with being an independent department: control over the physical space in which faculty members reside.

“We’re really excited about having a more collaborative physical layout,” Cormen said.

The new space’s proximity to Thayer and the Tuck School of Business will also facilitate interdepartment collaboration, according to Cormen. There is already significant overlap between the fields of computer science, business and engineering, and Cormen hopes the move will facilitate further conversations.

And who knows, perhaps a new digital arts department — nestled in the intersection of arts, computer science and entrepreneurship — will be the next unfamiliar academic acronym to show up in our newsfeeds.