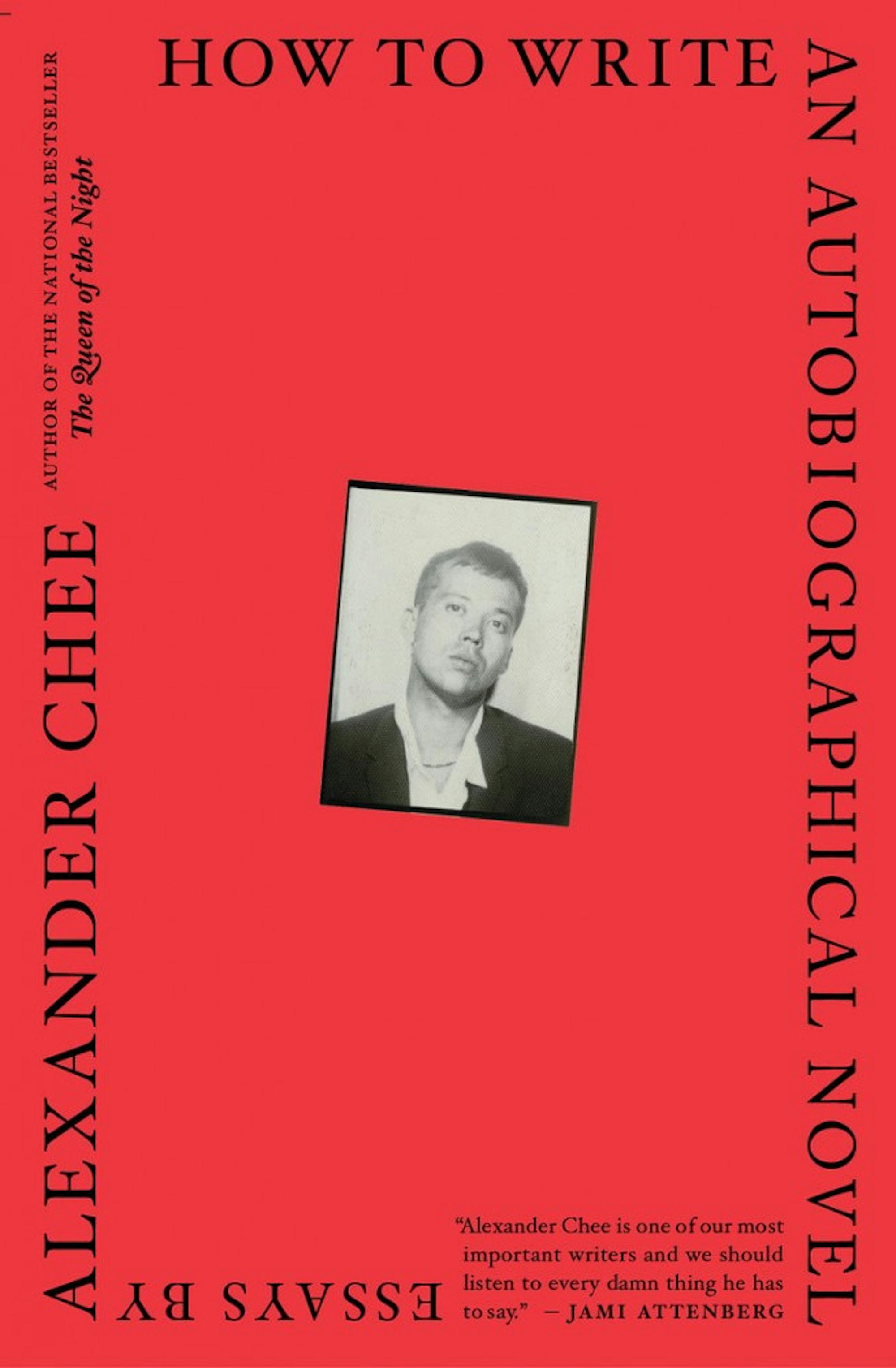

Dartmouth professor and best-selling novelist Alexander Chee’s new book “How to Write an Autobiographical Novel” is a collection of 16 nonfiction essays. The language is beautiful, the subject matter variegated and the insight profound. The essays are ordered chronologically, tracing Chee’s life through personally and politically transformative moments. While “How to Write an Autobiographical Novel” follows Chee’s journey as a writer, the book also details Chee’s many roles as student, cater-waiter, activist, gardener, lover, friend and teacher. In writing about his own selfhood, Chee explores large-scale political issues: the AIDS epidemic, the Iraq War, the 2016 presidential election. This book is a deep dive into Chee’s craft, a political thinkpiece, a memoir and a call to action.

The book begins in 1980, with Chee’s description of his time in Mexico as a 15-year-old foreign exchange student. “The Curse” is not only a coming-of-age essay — the piece also offers insightful commentary on belonging, sexuality and wealth disparity. Chee’s other essays address many subjects including personal trauma, family economic strain and his experiences as an activist in the fight against AIDS with the organization ACT UP. The intimate autobiographical narratives offer a window through which to see larger-scale national and international problems. Chee offers nuanced commentary on pressing political issues of the past and present, dexterously layering micro and macro narratives on top of each other, while obscuring neither.

In the third essay, entitled “The Writing Life,” Chee begins with a cyber-artifact from his past: an email addressed to Annie Dillard asking to join her nonfiction class at Wesleyan University. Chee introduces us to his young writer-self, “an English major who had failed at being a studio art major and thus became an English major by default.” How lucky the reader is for Chee to have failed in one artistic field and to have had so much success in another. In subsequent essays, Chee talks about his circuitous path to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and his choice to become a professor. He discusses the technical and life lessons he teaches his students, advice he imparts to the reader by default. Near the end of the book, Chee discusses the worth of writing and of teaching writing. He writes about how strange it is to teach a craft that no state power wants taught.

Chee wrestles with the systematic forces which seek to silence artists and inhibit his role as a writer. He speaks to the condition of being an artist in America, grappling with a country fraught with systematic wrongdoing. He speaks about juggling jobs, in one essay detailing his time as a waiter for William and Pat Buckley. Chee’s winding journey is an admirable lesson that endurance in the face of hardship breeds success.

The recurring themes and symbols of a singular life weave through Chee’s separate essays, forming a continuous narrative of memory and reflection. Chee’s exploration of his family history, his activism, his identity as a queer man of color and his rose garden are threaded throughout the collection. These various subjects conjure a multi-layered world. Chee is a master of his craft. He not only writes beautifully, but parses out the writing process, showing a deep understanding and love of his work. His two essays “100 Things About Writing a Novel” and “How to Write an Autobiographical Novel” transform the lowly list into a lyrical, sinuous form. Chee is very funny — he writes of a “certain Beat poet,” describes drag in the Castro as a “competitive sport” and calls himself at one point a “Connecticut Persephone,” traveling frantically between Wesleyan and Manhattan. Chee’s prose is at once lovely and weighty. If Marianne Moore’s poems are “imaginary gardens with real toads,” then Chee’s language contains these very toads, cloaked in gossamer.

Chee intuitively describes his condition as a writer, where “watching both hid[es] him and g[ives] him power.” In one essay, Chee makes a heartbreaking study of his friend Peter, who dies of AIDS in the 1990s. There are a few of these eulogies, whether they are identified as such or not, scattered between essays of rose gardens and tarot card readings and drag queens and cater-waiter escapades. In one essay, after 9/11, the ashes of the dead clog Chee’s asthmatic lungs; in many others, he describes friends who die of AIDS. So many deaths exist amidst this story of one man’s life. Chee does not fall into sentimentalism but instead explores each person with complexity. He historicizes his friends’ deaths to great effect, highlighting what each death meant within a greater political context.

“What is the point?” Chee asked in the collection’s final essay, “On Becoming an American Writer.” He describes how a student asks him this question the day after the 2016 presidential election. Every major news outlet had predicted one outcome, and yet at the uncanny hour of three in the morning on November 9th, newscasters announced that the terrifying alternative had come to pass — a deafening result that continues to silence so many. Why write into the erasing wind? Why write if there is nobody to listen? Sifting through the book, Chee’s answers to this question are easily spotted. Chee instructs the reader, his students and himself to write beyond all perceived failings of craft and self. To imagine is political: to create is to resist; to write is to discover selfhood and solutions. To tell one another our stories is the most human thing we can do. “Write for your dead,” Chee asserts. This is his answer. This is his mission.

It is interesting that Chee ends the book by speaking not about his own writing, but about his role as a teacher. Knowing Professor Chee, this conclusion is characteristically humble, though he has accomplished so much. “It is a strange time to teach someone to write stories,” Chee writes. Yet, in the penultimate essay, he urges the reader forward. “Here is the ax,” he says. Write. This is how you write an autobiographical novel.