Best friends often share similar tastes in everything from music to clothes, but what if they also have similar brain activity?

In a study published on Jan. 30 in the scientific journal Nature Communications, researchers determined that similarities in neural responses from fMRI scans can be used to predict friendships. The study was led by Carolyn Parkinson, a psychology professor at the University of California, Los Angeles; Adam Kleinbaum, a business administration professor at the Tuck School of Business; and Dartmouth psychological and brain sciences professor Thalia Wheatley. The researchers’ findings suggest that individuals who are friends perceive and respond to the world in similar neurological ways.

“One of the most well-established findings that we’ve known about for decades is that people who are similar are more likely to be friends,” Kleinbaum said, adding that a shared race, ethnicity, gender or nationality is a contributing factor towards friendship.

“We wondered whether people who are similar on a neurological level are more likely to be friends,” he said.

The inspiration for the study came from previous research that suggested that certain demographic factors can be predictors of friendship, Kleinbaum said.

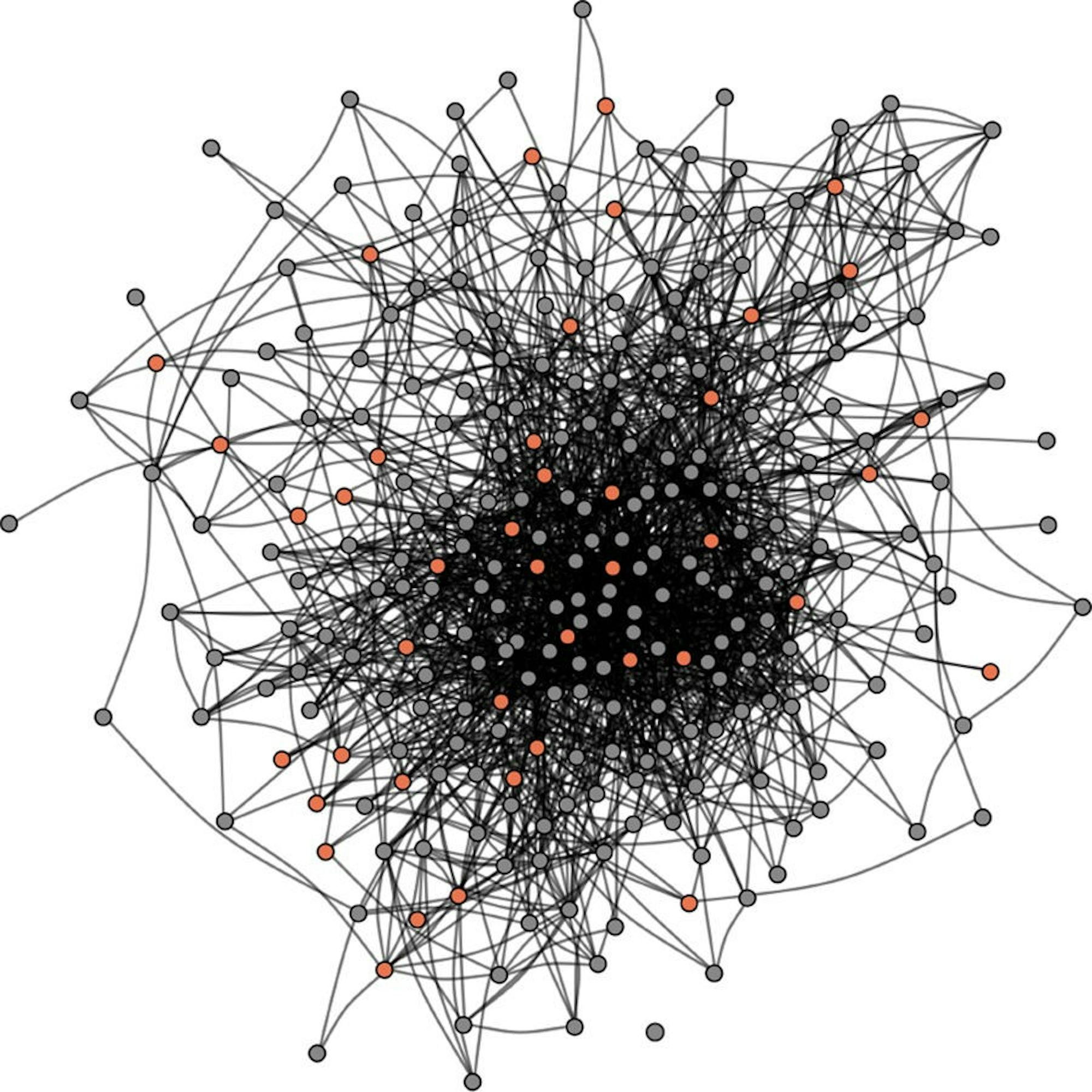

The first step of the study included mapping the social network of a cohort of 279 first-year graduate students at a private university in the United States. An online survey asked with whom the students were friends; the researchers used the results to construct a social network mapping reciprocal friendships, which estimated social distances between individuals. Of the students in the cohort, 42 individuals then participated in an fMRI study to measure their brain activity in response to video clips.

During the fMRI study, the researchers showed each participant the same collection of video clips, ranging across genres such as comedy, documentaries and debates, Wheatley said. The videos were chosen to be engaging and divergent, Kleinbaum said, meaning that they were meant to capture participants’ attention as well as inspire different reactions. He said video clips were used in part because they allowed the researchers to compare neural responses at specific instances in the videos.

“We were interested in naturalistic stimulus — the kinds of things that people would experience in the real world,” Kleinbaum said. “Showing a series of video clips was the closest thing we could get to real-world naturalistic stimulus that we could expose people to while recording their brain activity.”

The most surprising part of the study was the large scale of similar responses across friends’ brains, Wheatley said.

“We were surprised by how big of an effect there was and how widespread it was across the brain,” she said, adding that the researchers were not sure whether they would see an effect at all. “But we saw this pattern where friends were remarkably similar compared to friends of friends compared to friends of friends of friends.”

The researchers concluded that people whose neural responses to the experiment’s videos were more similar were also more likely to be closer to one another in the social network. Even when accounting for variables like age, gender, nationality and ethnicity, the correlation between neural response and distance in the social network was statistically significant.

“Most people know that there’s this ‘birds of a feather flock together’ idea,” said Nicholas Christakis, director of the Human Nature Lab at Yale University, who studies biology and social networks. “What this paper shows is that this type of homophily extends to a different level of biology than our superficial traits.”

He added that natural selection has shaped the friendship preferences in humans such as the number or kind of friends.

“The work in the Wheatley lab provides another brick in the wall proving this,” Christakis said.

While there are benefits to befriending people of similar neural behavior, Kleinbaum said it remains important to seek out people who think in other ways.

“People who are different from us challenge us to think about things differently, to think more deeply, to understand issues from different perspectives,” Kleinbaum said. “I think what this study shows is that it’s easy to fall into relationships with people who see things the same way that we do, and if we want the benefits of diversity, it requires a more deliberate effort.”

Kleinbaum said he believes that people can still overcome differences in neural responses by purposely interacting with people who might view the world differently.

“I hope it’s not just that we are a certain way, and we simply find people who are exactly the same as we are,” Wheatley said. “That phenomenon would lead to echo chambers and polarizations.”

According to Kleinbaum and Wheatley, their future research related to this study will attempt to differentiate whether friends have similar neural activity because people tend to seek out like-minded individuals or if spending time together causes neural activity to become more similar. Kleinbaum said their current research could not separate between selection effects — people choosing to be friends with like-minded individuals — and convergence effects, which is people becoming more similar after becoming friends.

Human beings are a unique species in that they form “longterm, non-reproductive unions” with other members otherwise known as “friends,” Christakis said.

“I think there’s going to be a lot of work in the coming years trying to understand the biology of friendship,” he said.

Maria is a freshman from Oak Brook, IL. Maria plans to major in Cognitive Science and minor in Computer Science, and she joined The D because she wants to bring attention to current events on campus. In her free time, she enjoys golfing, learning about new cultures, and playing with her two puppies.