Dartmouth’s financial statement for fiscal year 2017, released in October 2017, shows strong endowment performance and a decline in operating expenses compared to the previous year, alongside relatively small growth in revenues.

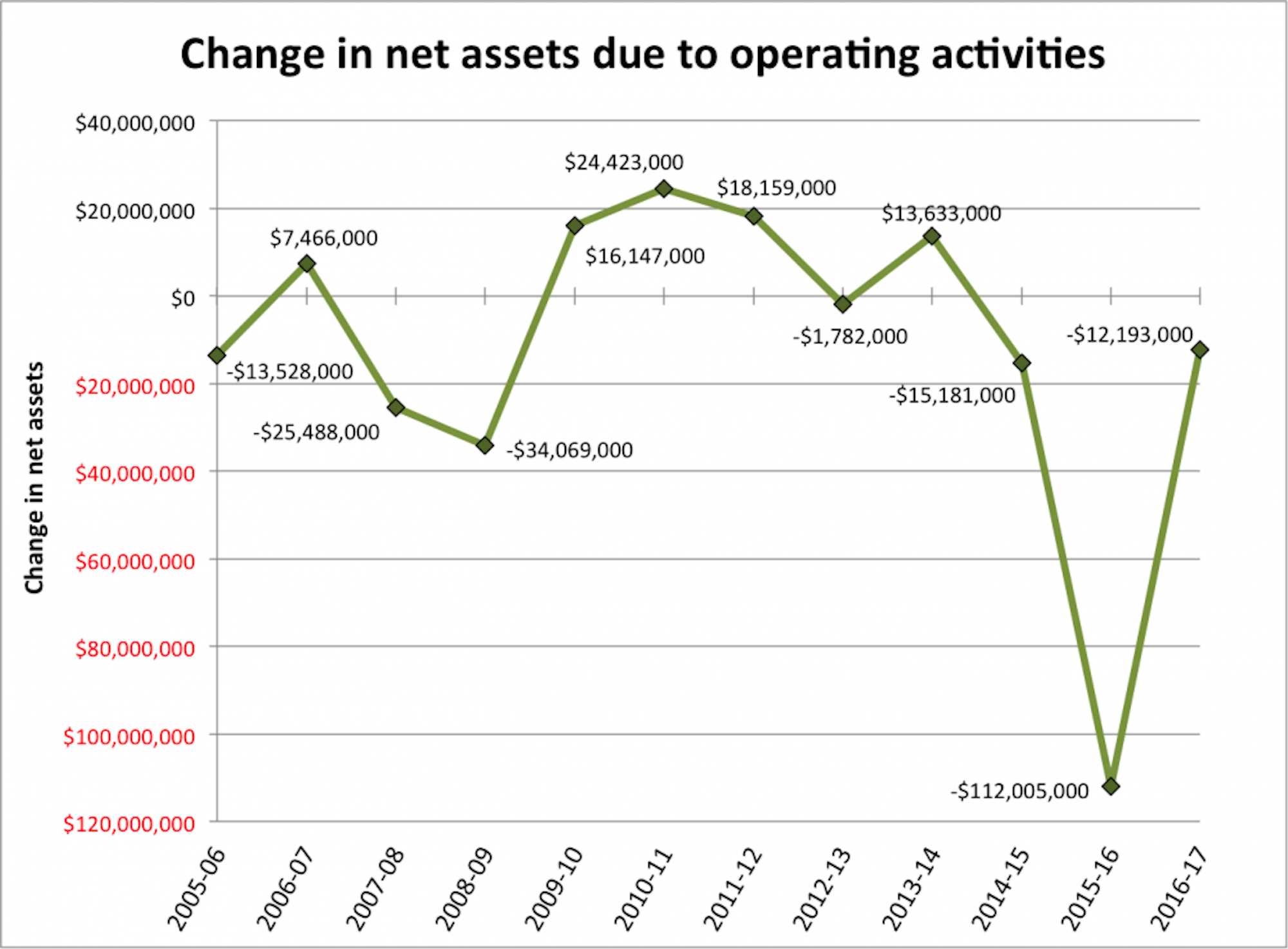

Net assets grew from $7.26 billion to $7.89 billion, an increase of 8.7 percent. Net assets from endowment activities grew by $482 million, compared to last year’s decline of $189 million, while revenues increased from $860 million to $889 million. While there was a loss in net assets from operating activities, the loss was much smaller than last year’s, at around $12 million compared to $112 million.

Some of the decreases in losses of net assets from operating activities are related to last year’s reorganization of the Geisel School of Medicine. Last year, all of the costs related to the reorganization — about $53.5 million — were listed under the College’s fiscal year 2016 expenses, even though they will be paid across future years. This year, many employees were moved off of the College’s financial statement and onto the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center’s.

Executive vice president Richard Mills added that there has been slower capital spending — money spent on constructing or renovating buildings — for fiscal year 2017, and that he expects to see similar behavior in fiscal years 2018 and 2019. He explained that as the College approaches a major capital campaign, it attempts to obtain funding for the project through a combination of fundraising and borrowing money.

“Dartmouth is still financially quite strong relative to many other institutions in higher education by most metrics of endowment wealth, size of the operating budget, things like that,” chief financial officer Mike Wagner said.

He added that the College is currently working to improve its standing compared to peer institutions with greater resources.

Wagner pointed to inflation as a challenge that the College has faced in the past year, noting that it has put pressure on Dartmouth’s ability to hire and maintain faculty and staff. It has also made it more difficult to keep utility rates and other costs the same year to year, he said. He also noted that there have been pressures in the current political climate to decrease research funding, which could affect students’ opportunities to work in labs and conduct research, both at Geisel and the College of Arts and Sciences.

In addition, the College continues to be committed to meeting students’ full demonstrated financial need and offering need-blind admissions to domestic students, Wagner said.

While investment performance over the past year was good, there is no certainty that it will remain so in the future, Wagner said. Therefore, the College does not plan its budget with the assumption that future years will look like this one.

A major difference for the College this coming year is a new tax on endowments from the landmark Republican tax bill passed last December. It adds a 1.4 percent excise tax on realized gains from the endowment — interests, dividends and other income realized in cash — for any university with more than 500 students and an endowment worth over $500,000 per full-time student. Around 30 colleges and universities have large enough endowment-per-student ratios to be affected by this tax. This ratio comes to around $720,000 to $750,000 of the endowment per student for Dartmouth, Wagner said. He noted that some other schools have much larger endowments per student, some in excess of $1 million. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, Harvard University, Princeton University and Yale University all have endowment-per-student ratios over $1 million.

The College would have paid about $5 million per year on average over the last five years if the new tax bill had been in place, Wagner said.

“In any one year, $5 million against $5 billion is relatively small, but over five years, that’s $25 million,” he said. “And if you invest that in the endowment, it really compounds and grows. So that’s what we’re more worried about ... the growth opportunity.”

The investment of Dartmouth’s endowment is closely governed by the College president, the investment committee of the Board of Trustees and the College’s investment office, Wagner said. These three bodies design an investment allocation portfolio that distributes portions of the endowment across different types of investments, such as private equity, venture capital, marketable securities, real estate and other hard assets. Hundreds of managers invest the money, monitoring the markets closely and aiming to maximize returns.

Dartmouth’s endowment has about a 5 percent distribution rate, meaning that five cents are given to the College to spend on different programs for each dollar donated to the school. Though it can be tempting to distribute more in the short term, investing more in the College’s endowment is more beneficial in the long run because funds will accumulate and result in different programs having more money in the future, Mills said.

“It comes down to balancing between short-term spending and long-term investment,” he said.

A article published by The New York Times in November revealed that Dartmouth is one of several colleges and universities that have used “blocker corporations” to partner with hedge funds and private equity groups to invest borrowed funds in profitable offshore holdings. While endowment earnings have traditionally been tax-exempt, these funds earned with borrowed money can be taxed because they are not related to the universities’ education missions. By forming corporations to receive these investment profits, rather than having them go directly to the endowment, universities are able to avoid these taxes. The New York Times reported that under the House version of the Republican tax bill, these blocker corporations would also be exempt from the new 1.4 percent endowment tax.

Asked about the College’s overseas investments, Mills said that the College’s goal is to minimize its effective tax rate to earn money and support its continued functioning.

“When you think about the purpose of the endowment, it’s to maximize returns to support the academic mission,” Mills said. “And taxes dilute returns because if you invest and it’s taxed, the net return after taxes is smaller. So every endowment, every investment vehicle, looks at, ‘How can we invest?’ and ‘What are the investment options to minimize tax exposure?’ And that involves all kinds of different techniques.”

He noted that the College has not moved all investments overseas in order to maintain a diversified portfolio and because some U.S.-based investments are still more profitable than overseas investments, even with higher tax rates.