Last week, over 40 teachers from across Mexico gathered at Dartmouth for a two-week program led by the Inter-American Partnership for Education, held in partnership with the educational nonprofit WorldFund and the Rassias Center for World Languages and Culture. This year, the program celebrated the tenth anniversary of its commitment to bridging the gap between Mexico and the U.S. through education.

According to the WorldFund website, IAPE trains English language educators to create educational change in classrooms across the country. The group offers three programs — two in Mexico that focus primarily on Spanish language development skills and one at Dartmouth that provides participants with over 130 hours of intensive workshops, training and cultural activities. Following two weeks in Hanover, participants are required to provide 100 hours of commitment to public education in Mexico, including participation in IAPE over the following three years through workshops, conferences and academic journal articles.

The Hanover program focuses on teaching the Rassias method, developed by the late professor John Rassias, who taught at Dartmouth from 1965 to 2015. The Rassias method is a rigorous and interactive system based on the idea that students speak to learn rather than learn to speak, according to the WorldFund website. Since its founding, the Rassias method has been used to train more than 165,000 Peace Corps volunteers, as well as countless students and teachers throughout the world, in foreign languages.

In March 2006, the program in Hanover was planned under IAPE’s current director, Jim Citron ’86, and Helene C. Rassias-Miles, the executive director of the College’s Rassias Center for World Languages and Cultures and Rassias’ daughter.

From the beginning, Rassias wanted to ensure that the program would be sustainable and create an opportunity for participants to act as a support system for each other.

“My dad was very adamant about not just holding workshops and getting people to come to Hanover and that being it,” Rassias-Miles said. “Eventually, we want to make this a part of a whole country-wide plan to allow people to help their colleagues.”

The initial pilot in Mexico hosted 18 teachers. The first program at Dartmouth was held in July 2008.

In November 2007, less than a year before the first on-campus pilot programs, Citron remembered being unhappy with his current job and wanting a change of pace.

“I just remember saying I wanted to do something with a more social service mission that uses my Spanish skills, teaching skills and knowledge of Mexico,” Citron said. “One of the first things we did when I started was [to come] up with a name for the program. And we came up with IAPE, because it’s a partnership between ... WorldFund, the Rassias Center, the founding partners and the fundraising partners.”

This year’s program invited 30 participants and four advanced trainers to Dartmouth. The advanced trainers had all completed the program in years past and have all previously made a significant impact in English education.

“The first time we did the application process, we realized half of the participants didn’t have the English skills yet needed to complete the program,” Rassias-Miles said. “We aren’t teaching English, we are teaching them how to teach English with the Rassias program.”

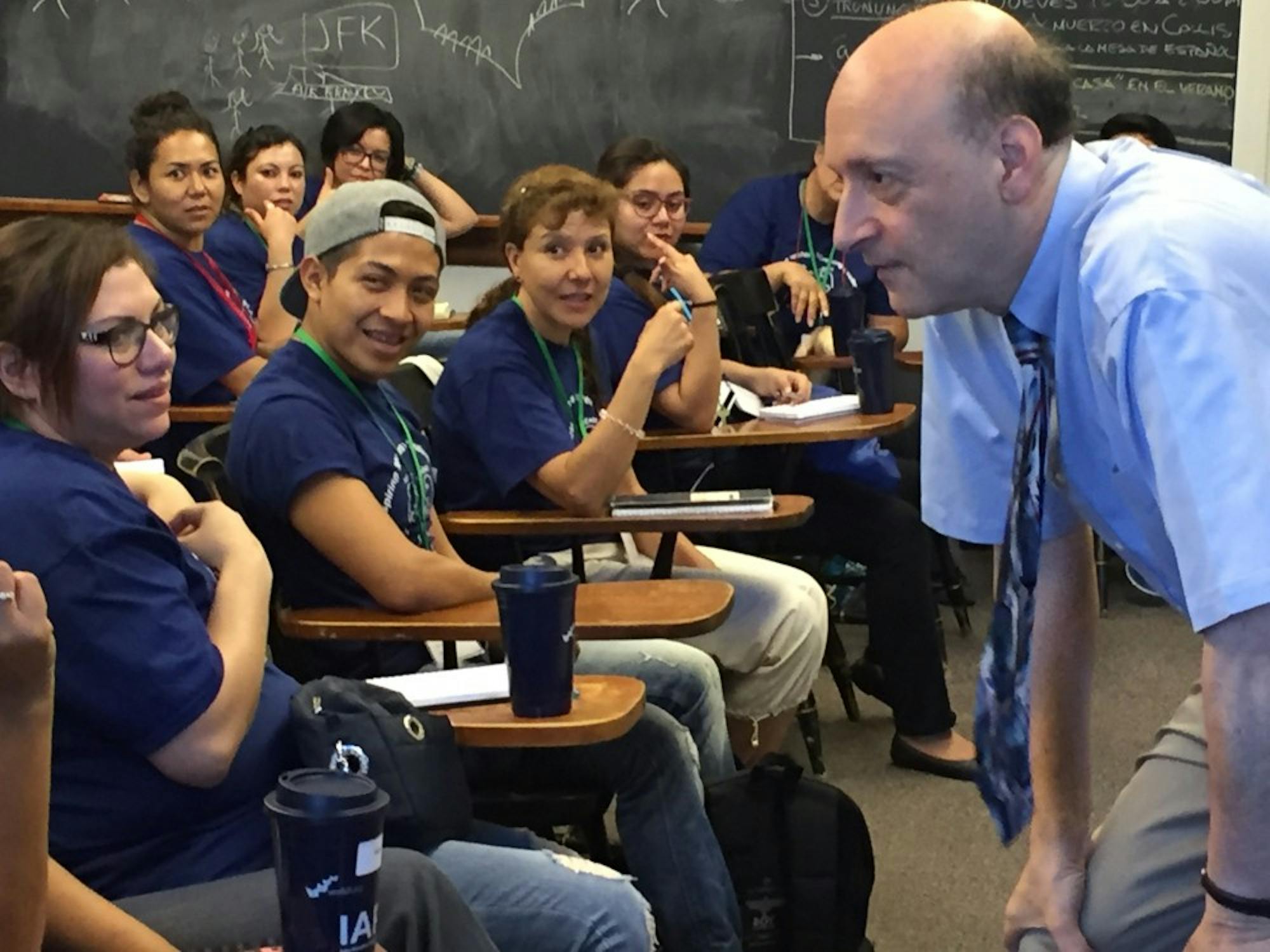

On campus, the program allows participants to attend lecture courses in the morning. According to Rassias-Miles, during the two-week experience, participants use what they have learned to teach their native Spanish in classrooms in Newport, New Hampshire in order to practice the Rassias method.

Among the educators involved in the program, there is heavy representation of Dartmouth alumni, with volunteers coming back to campus from New York and Connecticut.

“Everyone participates to do different things to help perpetuate, [be] change agents and contribute to the multiplier aspect of the program to help eventually spread learning methods,” Rassias-Miles said.

According to Citron, each scholarship costs approximately 5,000 dollars to host the teacher participants on campus. In turn, each teacher impacts an average of 250 students a year for three years following the program. Instruction taught through IAPE has already impacted 2.1 million students.

Recent studies suggest that professionals who speak English in Mexico, held constant by academic level and job training, earn 28 percent more during their lifetime, Citron said. In addition, there has been a recorded difference in English skills between private and public school students. “What we are trying to do is level the playing field and give advantage to the 86 percent of kids in Mexico who attend public schools,” Citron said.

Abril Orozco, a teacher from Campeche, Mexico who locally coordinates the national English program, is a participant in this year’s program. Orozco said the Rassias method was particularly unique because it allows educators to teach grammar and improve their students listening skills.

“Sometimes you lead a class but only visual students might learn,” Orozco said. “If you not only use visuals, but listening and audio skills, the students learn much better. If you put yourself in the place of your students and realize that you are learning, they will learn.”

Orozco also said that one of the best parts of the program is coming to Dartmouth and being immersed into the American culture.

“Here, you get to know how Americans behave and all of these influences on the American language,” Orozco said. “The life on campus is a dream, a limited and small city where you can go everywhere and do everything … it’s beautiful, peaceful, and people here are conscious about the environment.”

Emir Ramírez, an advanced trainer from Chiapas who teaches teenagers ages 12 to 15, initially heard about IAPE in 2008. Ramírez described an increase in students’ participation in classes as a result of the Rassias method.

“It’s more than just changing teaching styles; you are touching your students’ heart[s],” Ramírez said.

Alejandra Cabrera is a university professor who is working to help engage students at the university level. Currently working at the Universidad Politénica de Yucatán that is known for being bilingual, international and sustainable, the school teaches engineering subjects in English. Each student enrolled in courses spends the first quarter, approximately 525 class hours, in English immersion courses. This year, the university sent ten students to the U.S. and Canada to further their engineering studies.

“I’m really proud because the university just opened in September, and us being able to already send students to the United States makes us happy,” Cabrera said. “Next year, I want to be able to not just send ten students, but 20, 30 or even 40, and I think the Rassias method is going to be the key to reach this goal.”

Mireya Fuentes, a teacher from Sinaloa, Mexico, hopes the Rassias method will help connect her students in the classroom, especially at a politically uncertain period in her home state.

“My state is facing a lot of problems right now,” Fuentes said. “The government is against us and this method is not only helpful for learning a language but will be more effective with students. If they have problems, you can bring up another technique and control the environment … I think it’s going to help us connect with other people.”

Fuentes also said she believed one of the key factors of teaching is connecting with her students.

“These methods have all the requirements to improve our English classes right now, and I strongly believe this is going to change many lives,” Fuentes said. “We are facing negative global problems and I think this process will really help — for me, it has been great to be here, practice new stuff and learn from the best teachers.”

Julieta Sánchez, the coordinator of admissions and external relations at WorldFund, said the process is essential for the development of overall English language skills in Mexico.

“In Mexico, we have had English classes in middle school for many years, but studies show the teachers don’t actually speak English in class,” Herrera said. “Here, it’s about learning to teach others and the cultural environment to learn more about education from different aspects.”

IAPE academic coordinator Raúl López gave a similar perspective. As the coordinator of the program, López highlighted the positive impact of the nontraditional approach in Mexico.

“The basis of the Rassias method and philosophy is really what creates the impact in teaching … it’s uplifting the fears you have when you speak a language,” López said. “When you make mistakes it’s fine, and I think that’s the most valuable lesson the students get — that’s how they break their limitations to speak ... creating a truly bilingual country that will open doors to the world.”

Paulomi is a junior from Connecticut and at Dartmouth she is an Economics and Government major with a public policy minor. Outside of The Dartmouth, Paulomi is involved with Women's Club Lacrosse, the Rockefeller Center for Public Policy, and Women in Business. Paulomi is excited to travel to Antarctica in winter 2018 to study public policy in the field.