Not all the old traditions fail. Over spring break, Dartmouth students kept one tradition alive by contributing to the age-old process of maple sugaring in the Upper Valley.

A group of 10 students participated in the sugaring process on Dartmouth’s Organic Farm, the third consecutive year of operation for the alternative spring break project.

Beginning in mid-February, students ventured to the farm to begin tapping maple trees. In total, they tapped 90 trees, program manager Laura Carpenter said. Ideally, the trees should be tapped before it starts to thaw outdoors and the sap starts running, she explained.

Maple specialist at the University of Vermont Mark Isselhardt, who communicates with local sugar producers throughout the region and keeps a sugaring blog, said that in Vermont, people are having a good to excellent season. Isselhardt anticipates that there will be above average production state wide. Average production is 0.31 gallons of syrup per tap per year.

The sap runs most frequently and in the greatest volume when it is above freezing during the day and the temperature dips below freezing at night, environmental studies professor David Lutz said. Lutz, an expert in forest ecology, said pressure develops in the trees during warmer periods, forcing the sap out through the tap hole. In contrast, cooler periods cause negative pressure to develop, drawing water into the tree through its roots and replenishing the sap supply, he said.

Because this year’s temperature gradient was atypical, there was sap flow even before the sugar crew sank their taps in.

“For us, it’s been a fairly nice year,” Lutz said. “The sugar crew probably had a medium year. They were a little off, because they generally don’t tap until spring break. They missed some of the early runs that the data collection group did.”

The winter’s warm spells actually aided sap flow, Lutz said. Although daytime temperatures floated into the 60s, the temperature still plummeted at night. This sharp contrast is precisely what gives rise to a huge flow, he noted.

So far in 2016, production has been high, but it is not clear how long collection will last, Lutz said. In previous years, collection ended in late April.

The season draws to a close when leaves begin to open, Lutz said. As the plant awakens, there is more microbial activity and secondary metabolites — nonessential defense compounds — are produced in greater quantities, resulting in a murky, unpalatable sap, he said. Without fluctuations in temperature, the pressure gradient also dissolves.

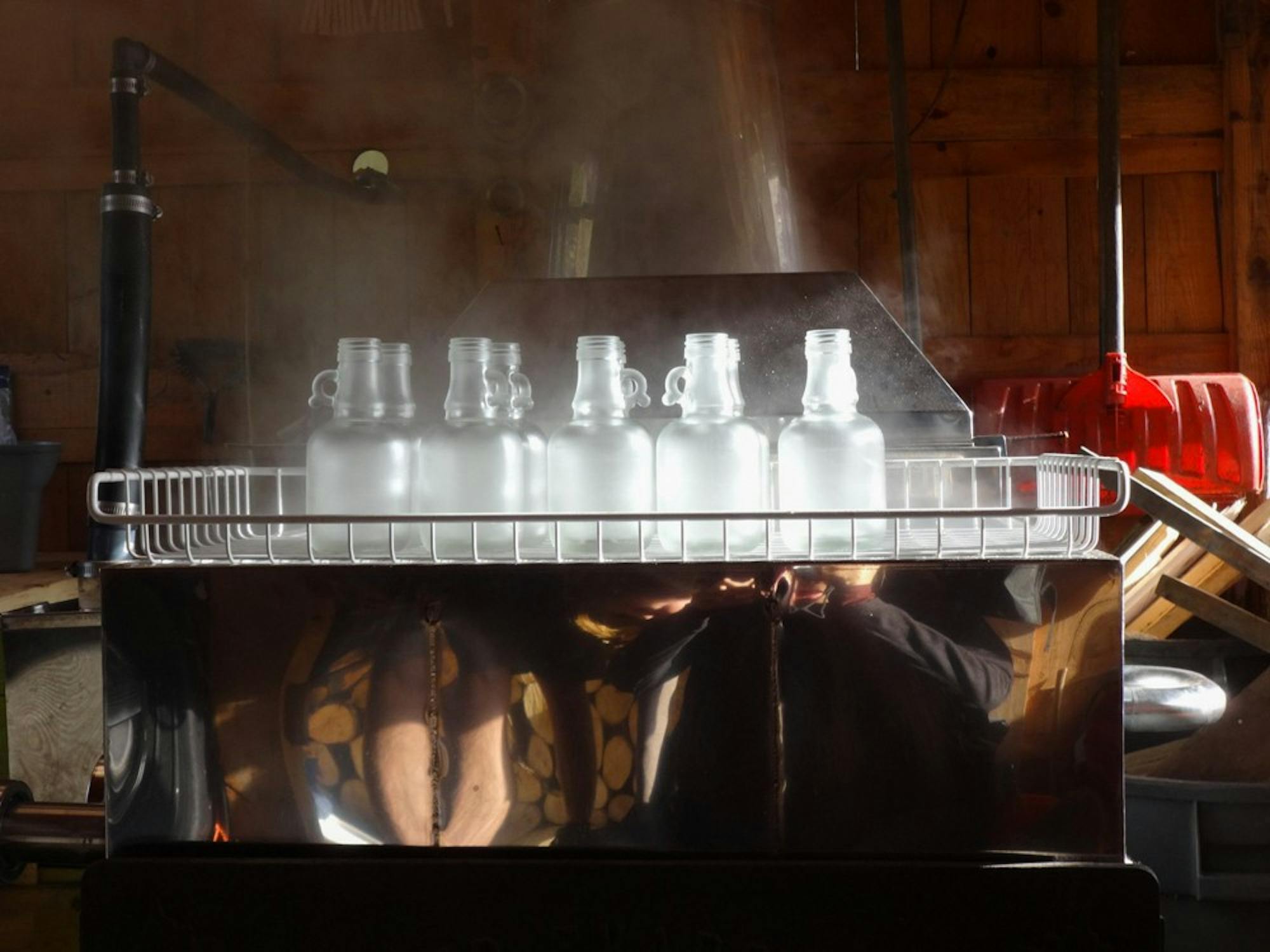

Rather than using a line to connect tapped trees to large collection basins, the Dartmouth students sugaring this spring relied on buckets. Upon concentrating the sap in a large stainless steel pan, the students were responsible for boiling it to produce syrup.

The sap initially has a 2 to 3 percent sugar content, while maple syrup is roughly 67 percent sugar, crew member David Ringel ’19 said. It takes 35 to 40 gallons of sap to produce a gallon of maple syrup.

According to Ringel, the consistency of the sap changes more than the taste. While the unprocessed sap, sometimes known as maple tea, is clear and resembles water, it becomes more viscous and darker with boiling.

Determining when to stop boiling is the most difficult part of the sugaring process, Ringel said. Taste and consistency can be used to evaluate the readiness of the syrup, though the group relied most on the change in boiling point, Ringel said. Maple syrup boils at 219 degrees, 7 degrees above the boiling point of water.

Most of the boiling was done by the team’s co-leaders, Claire Park ’16 and Dana Wieland ’17. However, the last day included a “passing of the torch to the ’19s,” as Ringel and Amanda Zhou ’19 were tasked with the final boil.

“Most memorable was probably spending time in the shack when we were boiling with everyone, smelling all the maple smells and watching the light filter into the room,” crew member Ellen Kim ’17 said.

Although Wieland and Park did not intend for the process to be competitive, they had to turn applicants away in order to maintain a small, cohesive group, Park said. The two tried to select a group that was balanced in terms of gender and class years, Wieland said. They wanted enough freshmen to keep the program going and enough workers with some level of expertise, she added.

About a third of the crew was involved in the Dartmouth Outing Club or Office of Sustainability, a third were new to the farm and another third were past sugar crew members, Park said. The resulting crew was “a group of like-minded students with a can-do attitude,” Ringel said.

Overall, the team produced about 7 or 8 gallons of maple syrup. Most of the supply will be given to Dartmouth’s Advancement Division, which will send 8 ounce bottles of syrup to donors and alumni, Carpenter said. The remaining syrup will be packaged in small bottles that will be available for sale in Collis in the next two to three weeks.

The sugar crew also took a number of field trips to nearby research and production facilities. A visit to Bascom Maple Farms, a large production facility and equipment supplier, demonstrated the commercial aspect of sugaring, Kim said.

Ringel called the visit to Bascom awe-inspiring.

“They produce more syrup every 15 minutes than we will do in an entire season,” he noted.

Bascom’s is one of six large-scale maple syrup producers in the Americas, Wieland added. They operate on a “mind-bogglingly huge scale,” she said.

The sugar crew also took a trip to Vershire, Vermont, where they met with Marc McKee, an informal advisor to the Dartmouth Organic Farm, Carpenter said. In Vershire, the crew visited the Mountain School’s sugar bush. McKee then showed the group his own sugar operation and hosted the students for a community pancake dinner he was holding. There, renowned environmentalist Bill McKibben presented a keynote speech on the effect of climate change on sugaring.

For Ringel, who read McKibben’s book “The End of Nature” (1989) for a class in the fall, the dinner was the highlight of the week.

“Vershire is a quintessential small town. The people are down to earth and the pace of life is slower,” he said.

The crew members also visited the Proctor Maple Research Center at UVM, Wieland said. The nature laboratory is on the cutting-edge of maple research.

“You might not think of sugaring as having a cutting edge, but it’s a big industry, so there’s incentive to make the process fuel efficient and to get more sap for tree,” she said.

Proctor is focused on maximizing yield from taps as well as answering basic science questions pertaining to the sustainability of tapping and the impact of modern technology on production, syrup chemistry and flavor, Isselhardt said.

More sugar than ever before can be collected with modern technologies and vacuums, but the long-term consequences on tree growth is still unknown, Isselhardt said. At Proctor, researchers are tracking a group of trees with different levels of sugar extraction over a period of 10 years to see if there are health effects resulting from tapping, he said.

Park enjoyed witnessing the contrast between people pursuing sugaring as a means of livelihood and scientists researching the process.

“[You] get to pick up on the culture of New Hampshire, which isn’t necessarily something you get at Dartmouth [as] Dartmouth is so much its own entity,” Wieland said. “There is a lot of reflection and a lot of being out there where it’s quiet, and you get to appreciate the farm and northeastern forests.”

According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service’s annual maple syrup production report, New Hampshire produced 4 percent of the national maple syrup product last year, while neighboring Vermont produced 41 percent of the national total. Overall, the northeastern region’s maple syrup production in 2015 totaled 2.96 million gallons, up 7 percent from the prior year’s production.

“Dartmouth is all about traditions and [sugaring] is such a tradition in the Northeast,” Ringel said.

Amanda Zhou ’19 is a member of The Dartmouth Staff.