What happens when a diagnosis does not provide clarity moving forward? For Junaid Yakubu ’16, learning that he had obsessive-compulsive disorder coupled with depression during his freshman winter only led to more questions. Though a clinician explained the details of treatment, stress and anxiety management, Yukubu was left with the dilemma of explaining what he was going through to family back home.

“Depression is something that’s at least understood in Ghana, but the OCD was the hard part,” Yakubu said. “I communicate so much with my mom, and I couldn’t with this. She understood the depression and it helped that we talked about it, but any mention of OCD would probably trigger a response of, ‘Let’s go get some prayers for you.’”

Among students of color, cultural understanding is one of many in the unique set of barriers to seeking services for managing mental health. Though no observable discrepancy exists in the rates at which minority students seek mental health treatment at the College, students’ understanding of mental health remains shaped by their culture and upbringing.

Bryant Ford, a clinician at counseling and human development at Dick’s House, noted that students tend to utilize counseling resources at rates corresponding with their representation on campus.

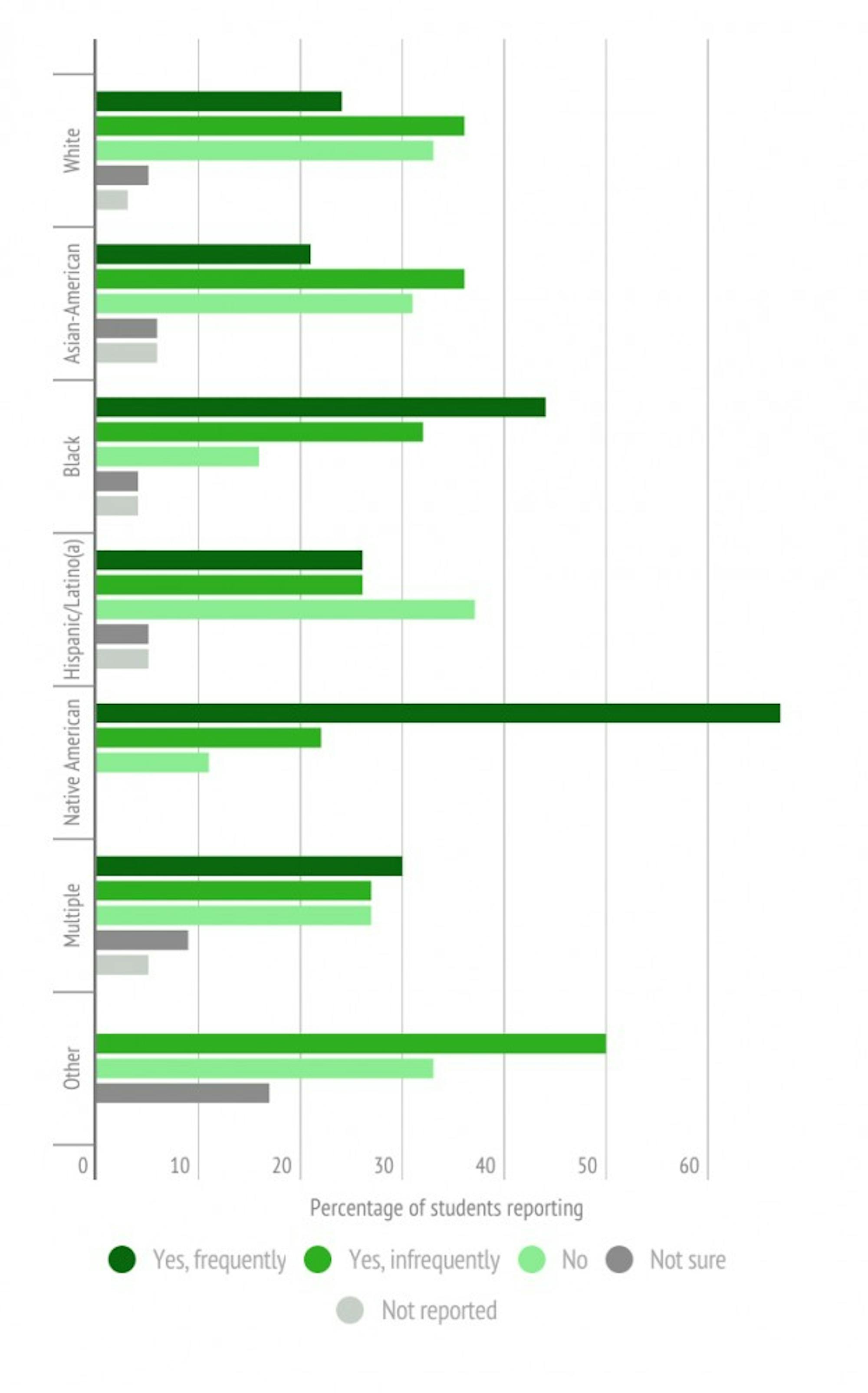

A survey conducted by The Dartmouth generally supported Ford’s statement despite some variation in certain groups. Among 515 survey respondents who marked their race, 66 percent were white, 4.8 percent black, 3.7 percent Hispanic/Latino, 14 percent Asian/Asian-American, 1.7 percent Native American and 8.5 percent multi-racial. Accordingly, of those who sought counseling at Dick’s House, 64.9 percent identified as white, 8.6 percent black, 3.9 percent Hispanic/Latino, 9.2 Asian/Asian-American, 2.6 percent Native American and 10.6 percent multi-racial.

Still, Ford emphasized that coming from a cultural background where discussion and understanding of mental health are not common can lead to misconceptions.

“When we start to look at the health-seeking practices of students of color, they sometimes look very different than from some of their white peers and counterparts,” Ford said. “Part of that is because there’s a negative connotation associated with mental illness. I think historically, sometimes health in general has created this, like some of the experiments that were done in the past which misled people to being mistrustful of seeking services.”

Unlike physical wellness and annual check-ups, it is rare for mental health to be screened regularly. As a result, access to treatment is dependent on the patient’s initiative, which can be difficult when there are language limitations, Ford said. He added that in some cultures, there are no words to describe conditions like anxiety or depression, which further makes these experiences seem invisible or illegitimate.

Arlene Velez, who also works at counseling and human development as a clinician, said that students more frequently come to Dick’s House for the somatic symptoms that emerge from mental health issues.

When a student arrives at the clinic for an appointment, they are asked two questions on the back of their sign-in slip: how many hours of sleep they get per night and how many drinks they consume in each sitting. Velez said the questions are part of a basic depression screening used across the country. The questions allow primary care providers to ask follow-up questions about a patient’s well-being based on their answers, often creating an opportunity to transition to discussions on mental health.

“Most students of color tend to reach out to medical providers for the somaticized symptoms of depression or anxiety instead of coming directly to us,” Velez said. “So from those questions, healthcare providers can possibly refer them to us or just open the door on really looking at one’s mental health.”

Yakubu said that when an illness is not physical, it is harder to find sympathy and understanding from friends. While an amputated leg or other injury can be seen and experienced by an observer, he said that frequently mental health was only felt internally. On the outside, observers only see mental illness when it manifests in behavior. Unfortunately, Yakubu added, individuals are often seen as responsible for controlling their behavior even if there are underlying factors.

“People can be so judgmental of behavior,” Yakubu said. “Compared to physical illness, or if you explain headache to family, they understand because they’ve been through it. But you try to explain OCD, and it’s hard to understand if you haven’t experienced it.”

Amara Ihionu ’17 grew up in a Nigerian-American family, where mental health was not openly discussed or acknowledged. She said that while something like non-verbal autism would be recognized as a special-needs condition, other conditions where an individual appears “functional” are not thought of as real illnesses.

“In Nigerian Igbo culture, we don’t talk about it,” Ihionu said. “If you’re relatively able to function, you’re told to snap out of it. It’s seen as a attitude problem, as under your control. It’s a thought of as a conscious effort you can make to fix yourself.”

Ihionu also said that family structure was a factor that shaped the conversation surrounding seeking a clinician, psychiatrist or therapist. In a family-centric culture, she said that parents and elders often question why their children would find it necessary to speak to a stranger about their personal struggles.

“There’s the idea of keeping it in the family, but sometimes your family can’t understand it,” Ihionu said. “Depression doesn’t need a reason, and if your parents don’t get that and you can’t talk to a clinician then the inability to have your feelings validated will only make the symptoms worse.”

Despite these gaps, Ford and Velez both said it was common for students to reach out to family to include them in the counseling process. Counselors then become involved in a sort of “education for parents,” Ford said, where possible misconceptions on mental health are corrected through discussions between students, family and staff.

Velez added that for students of color, being at Dartmouth can challenge how they perceive their own racial, ethnic and cultural identity. In a high-pressure, success-oriented environment, she added that minority students can often feel as if they do not have a place at the College. Factoring in mental health concerns can further compound these doubts.

“What I’ve seen with students of color is that their sense of belonging is challenged,” Velez said. “It’s like someone made a mistake, or that this place is not right for them. They end up comparing public personas with internal ones, and that adds different layers for students of color.”

Velez said that one of CHD’s major outreach goals was to normalize help-seeking. For students of color, undergraduate dean Brian Reed identified “stereotype threat” as a major barrier to reaching out for help. Individuals of any campus minority — racial, socioeconomic, disability — are often afraid of confirming stereotypes through their actions, Reed said.

“Students who already feel as if any challenge they experience here is because they’re inherently lacking, whether it’s not being able-bodied, being of low-socioeconomic standing or a racial minority, will find it hard to reach out,” Reed said. “There’s always a question of, ‘What might this say of the people I think I represent?’ — of reinforcing the stereotype.”

Though students may be strongly connected with their racial and cultural identity at home, Velez said that does not always mean they are comfortable with expressing those identities at Dartmouth. While cultural differences can be isolating and act as a trigger for mental health concerns, she said that increased community-based dialogue about race and identity could provide a feeling of validation through a “shared experience.”

Da-Shih Hu, a psychiatrist at Dick’s House, noticed the same issues being brought up repeatedly by his Asian-American patients — physical attractiveness, stereotypes, parental pressure — things that Hu himself said he struggled with at this age. In response, Hu teamed up with Sarah Chung, a psychologist at Dick’s House, to form the Asian-American Student Exploration Group. The group aims to create a space to discuss the Asian-American experience at Dartmouth. Past topics have included Asian activism, racism and body image.

Hu said that in Asian and Asian-American culture, emotional expression is understood differently than in broader American society. There is less of a focus on overtly expressing discontent and often, personal feelings may be subjugated to family needs. Unfortunately, Hu said that this can often be stereotyped as Asian-Americans being more emotionally distant than their peers.

Hu added that students of Asian heritage often come from a background where being less assertive is the norm, which can lead to misconceptions that prevent students from having their needs met and their voices heard.

“The repercussion from not speaking up is that people get used to Asians being silent,” he said. “It’s comparable to how we’re socialized to women not speaking up, so when they do it’s considered negative, pushy. People get used to Asians staying silent in the same way, so the ones who speak up are viewed as outliers than aren’t taken seriously, which just furthers this cycle.”

Hu said that the discussion group drew students from a range of backgrounds, from those born in the United States to international students coming from Asia. In the Western psychology viewpoint, Hu said that feeling comfortable with talking openly about problems is often assumed. He added that many students, however, come from a culture where it often may feel like it is not be their place to speak up. Despite mental health being acknowledged less widely in Asia, Hu said he was surprised and pleased by how open students were to considering a Western medicine point of view.

As the main psychiatrist at Dick’s House, Hu also works with students who are considering medication for managing their counseling treatment. Though the idea of taking a medicine to treat an illness is shared across cultures, chemical-based treatments for mental health can be harder to communicate across culture.

Sophomore winter, Yakubu was diagnosed with ADHD in addition to depression, anxiety and his existing OCD. While he started taking anti-depressants as prescribed, he rejected the idea of managing ADHD through medication. In his mind, ADHD seemed like laziness or an unfocused mind, something that required discipline more than anything else.

“Maybe it’s because I’m international, but in my mind it’s like, ‘Isn’t ADHD just an excuse?’” Yakubu said. “A part of me believes that you can’t help it because I’ve experienced it, but there’s a part of me that’s stubborn and rejected the idea of taking drugs for ADHD because it felt like cheating.”

Ihionu recalled the difficulty of communicating with her parents about beginning a course of anti-depressants. Though in the end she said she was able to open up to her mother and received support, she said that it was a stressful process until she reached that point of understanding.

As a beneficiary of her parents’ insurance plan, Ihionu had to make a number of additional considerations to keep medication confidential — paying out of pocket, which meant going on the generic because it is cheaper.

“It was so stressful that first round,” Ihionu said. “Now I’m on insurance, but obviously it’s not cheap even if you pay out of pocket, which I can’t imagine many people can do since [about] 50 percent of the College is on financial aid.”

Ihionu’s experience is common — despite active outreach efforts and activism from student groups, CHD and other offices on campus, systemic and institutional challenges remain for students of color seeking mental health.

Currently, insurance covers 10 counseling sessions per academic year at Dick’s House. Afterwards, students are referred to outside providers in the area, many of whom may be hard to access because their practices are located outside of Hanover. Transitioning away from a familiar clinician also disrupts the relationship and comfort built over time.

The D-Plan further complicates managing mental health concerns, Ford said. For students who go home to an environment where mental illness remains stigmatized, he said it was important to normalize the fact that the reality at Dartmouth could be more accepting of what they find at home.

“You have to let students know that the level of acceptance they feel here isn’t necessarily what they’ll get at home,” Ford said. “It’s why sometimes they don’t want to go home, because they feel like they can reveal a little bit of authenticity here. When you compartmentalize those pieces of yourself, it contributes to the mental health struggles of that.”

More than any other factor, students and experts said the hardest part to seeking treatment comes from experiencing mental health through multiple perspective — cultural, familial and being at Dartmouth.

Ihionu and Yakubu both noted a greater emphasis on the individual in American culture, which often makes pillars of mental wellness like “self-care” harder to understand for students from cultures with a more communal perspective. Yakubu used the example of his passion for filmmaking — while he enjoyed it, he struggled with the guilt of choosing a less financially secure path despite his responsibility to his family.

Velez and Ford both said that one way to balance individualism with community was to think of the self in the context of the group. Self-care can be as simple as taking a shower and getting enough sleep to be well enough to help the community, Velez added, using the analogy of “putting on your own oxygen mask before helping others” on a plane.

After managing his diagnosis after sophomore winter, Yakubu took a leave from the College to be at home with family in Ghana for a year. There was less communication than in the United States, less discussion of what mental illness was, but he added that being with family created a sense of support, even if the environment was less accepting and forced him to rethink mental health.

“In the local language, mentally ill is madness,” Yakubu said. “The kids would chant it and chase people, but they’re kids. Growing up, I used to do stuff that hadn’t been done before and people would say, ‘Oh, he’s crazy.’ It was something I was used to hearing about myself, but when I actually experienced mental illness, I was became more sensitive. It made me fear that it could be reality.”