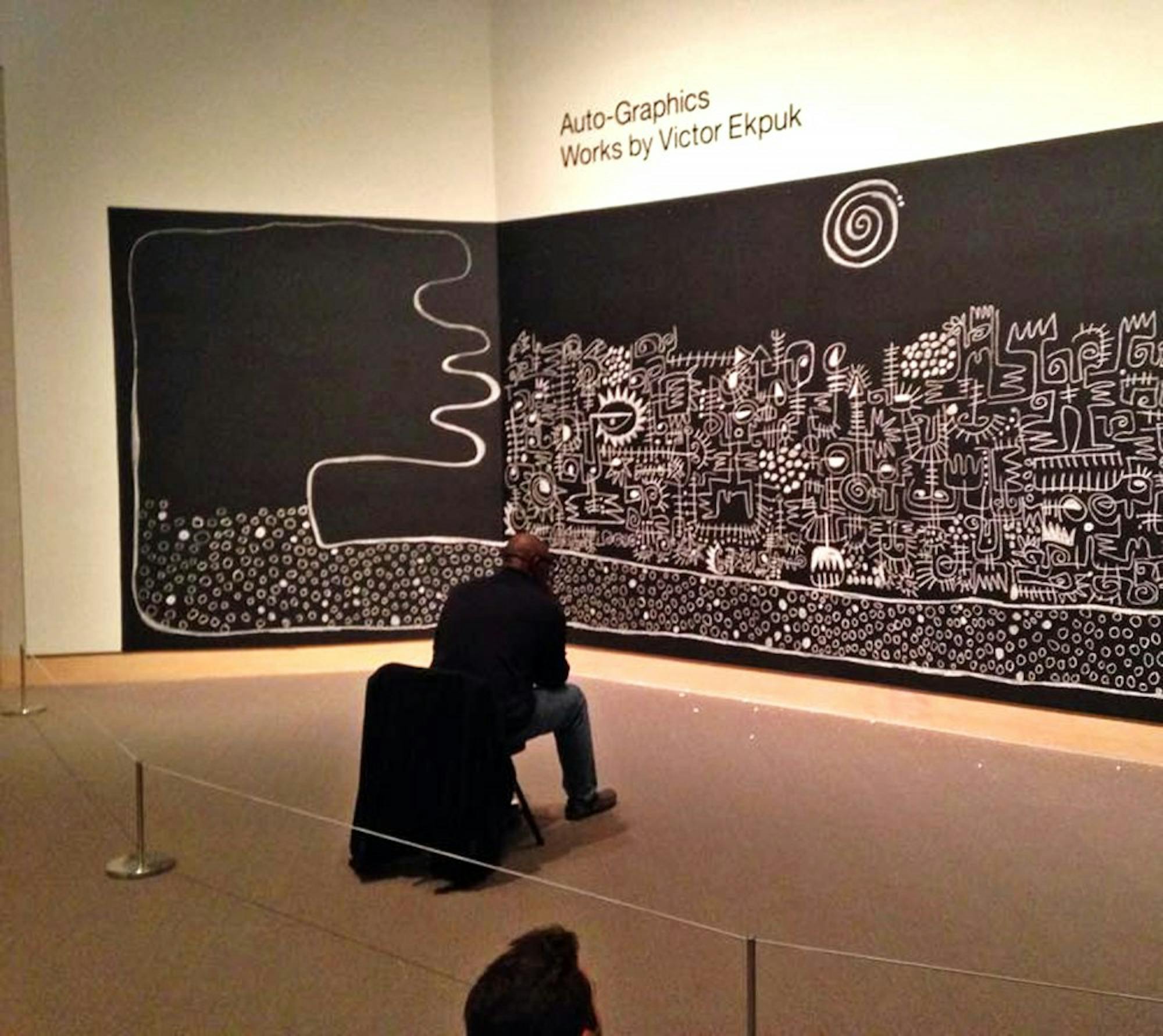

Closing Friday, Nigerian-born artist Victor Ekpuk will spend four days creating an original work on the wall of the Hood Museum’s Lathrop Gallery as part of his exhibition “Auto-Graphics.”

The exhibition, which opened at the Hood on Saturday, showcases Ekpuk’s bold, intricate forms and signature painting-like script. The exhibition, originally curated by Allyson Purpura at the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, contains 18 works and will remain at the Hood until Aug. 2nd.

Ekpuk said that “Auto-Graphics” is primarily a drawing exhibition, as he wanted to explore the form as its own medium. Creating graphic-based works, he primarily uses pastels and graphite on canvas, though he said he has incorporated collage and digital prints into the show.

Ekpuk is perhaps best known for his use of “nsibidi,” a type of symbol-based writing traditionally associated with the secret male Ekpe society from southeastern Nigeria, Hood Curator of African Art Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi said.

Ekpuk said that nsibidi relies heavily on symbols and body movements to communicate, and that he was inspired to make contemporary art out of an old system.

“My work is mainly about mining an old form of art and an old African idea of aesthetics and making contemporary statements from that,” Ekpuk said.

Ekpuk said that his fascination with nsibidi began during his art studies at Obafemi Awolowo University in Ife, Nigeria , where he explored the intricacies of pattern and design in indigenous African art forms. He said that he was particularly interested in nsibidi’s use of line and encoded meanings and how drawing and writing could be interconnected.

Ekpuk said that his studies of nsibidi have allowed him to develop his own fluid letterforms over time, using nsibidi as a “backdrop.” He said that he “doesn’t put emphasis on the meaning of the symbols” and has instead chosen to explore their aesthetic value. He said that he enjoys creating abstraction and reducing complex ideas and forms to basic symbols, and his art is saturated with distinctive dots, figures, scratches, scrawls and signs.

Hood curatorial intern Elissa Watters ’15, who worked alongside Nwezi to facilitate Ekpuk’s exhibition at the Hood, said that Ekpuk’s work revolves around recontextualizing.

“[Ekpuk] works with symbols, reinventing them and taking them out of the context of their meanings — sometimes he doesn’t even know what their meanings are,” she said.

Nzewi said that he has known about Ekpuk since 2009 and has been attracted to the “richness” of his practice ever since. Nzewi helped curate last year’s “Dak’Art” — the Biennale of Contemporary African Art in Senegal — and said that Ekpuk was one of the major artists featured there.

“One of the things we try to do at the Hood is show diversity of cultures — diversity of artistic practice — and so I felt it was important to bring [Ekpuk’s] work to Dartmouth because I think it’s good for our students and the studio program to be exposed to that,” Nzewi said.

Ekpuk described his drawing in the Lathrop Gallery as “a drawing performance.” The importance of memory and the desire to express cultural memory through art is another major sub-theme in his work, Ekpuk said. He explained that this live, temporary drawing on the museum wall will encompass this concept.

“Memory is something that informs our identity, and it is ephemeral in itself,” Ekpuk said. “When the exhibition is over the wall will be wiped off — a result of circumstance.”

Watters said that she enjoyed this interactive part of the exhibition, as seeing Ekpuk in action allowed her to participate more in his process of creation. She finds that artists usually become so “tied up” with their vision that the two become synonymous. Watters appreciated how Ekpuk’s physical presence allowed her to distinguish between the artist and his art.

“[Ekpuk’s] interactive art shows the way he thinks,” she said. “It is very spontaneous and reactive. It was interesting to see [Ekpuk] and how the art relates to him as a person — it is so personal.”

Vice chair of the English department Michael Chaney, who will be giving a talk in May linking Ekpuk’s work to 19th-century slave artisan Dave the Potter, said he will be comparing nsibidi to the secret form of communication used by African slaves, as both depended on coding. Dave the Potter would often write illegibly and incoherently on the outside of the clay objects he made, which Chaney said directly connects to the principles of nsibidi .

“Students will gain the ability to see what was formerly ‘invisible,’” Chaney said. “Learning about a visual tradition equips you with a way of seeing the world that you wouldn’t have otherwise.”

Ekpuk said that he would ultimately rather viewers consider his work more as “contemporary art” than “African art.”

“[Pablo] Picasso was inspired by African art, but that doesn’t make his work ‘African,’” Ekpuk said. “I want viewers to think more about how different cultures affect visual expressions.”

Nzewi said he appreciates how Ekpuk draws from disparate influences and takes inspiration from many unique sources, including textiles, writing and traditional African art forms.

“[Ekpuk’s] work speaks to contemporary art but also to anthropology,” Nzewi said. “His exhibition will resonate with the various constituents the museum serves.”