When geography professor Richard Wright mentioned to a class several years ago that undocumented immigrants attend Dartmouth, the room’s atmosphere shifted. Everything went quiet, he said. Most students seemed surprised.

First Year Student Enrichment Program Director Jay Davis said he works with several undocumented students in each class, but cannot approximate the total number of undocumented students on campus. Neither the Office of Visa and Immigration Services nor the Office of Admissions and the Financial Aid track the number of undocumented students attending Dartmouth.

Silence, and the inability of undocumented students to identify one another, has hampered the formation of a community among undocumented students on campus.

A male member of the Class of 2017, who is undocumented, said that fear associated with his immigration status has accompanied him since he left Mexico at age 5.

Many undocumented students choose not to tell others about their immigration status, leading some to feel “invisible,” said the male member of the Class of 2017, who requested anonymity to keep his status private.

Daniela Pelaez ’16, whose immigration battle was thrust into the national spotlight after her high school peers protested the valedictorian’s impending deportation, said the College lacks a network of undocumented students.

“It’s not like you are undocumented and therefore you know the other undocumented students,” she said.

Over the years, protests like a November 2011 hunger strike on the Green, which aimed to draw administrative attention to the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, have stirred campus discussion but not sustained activism.

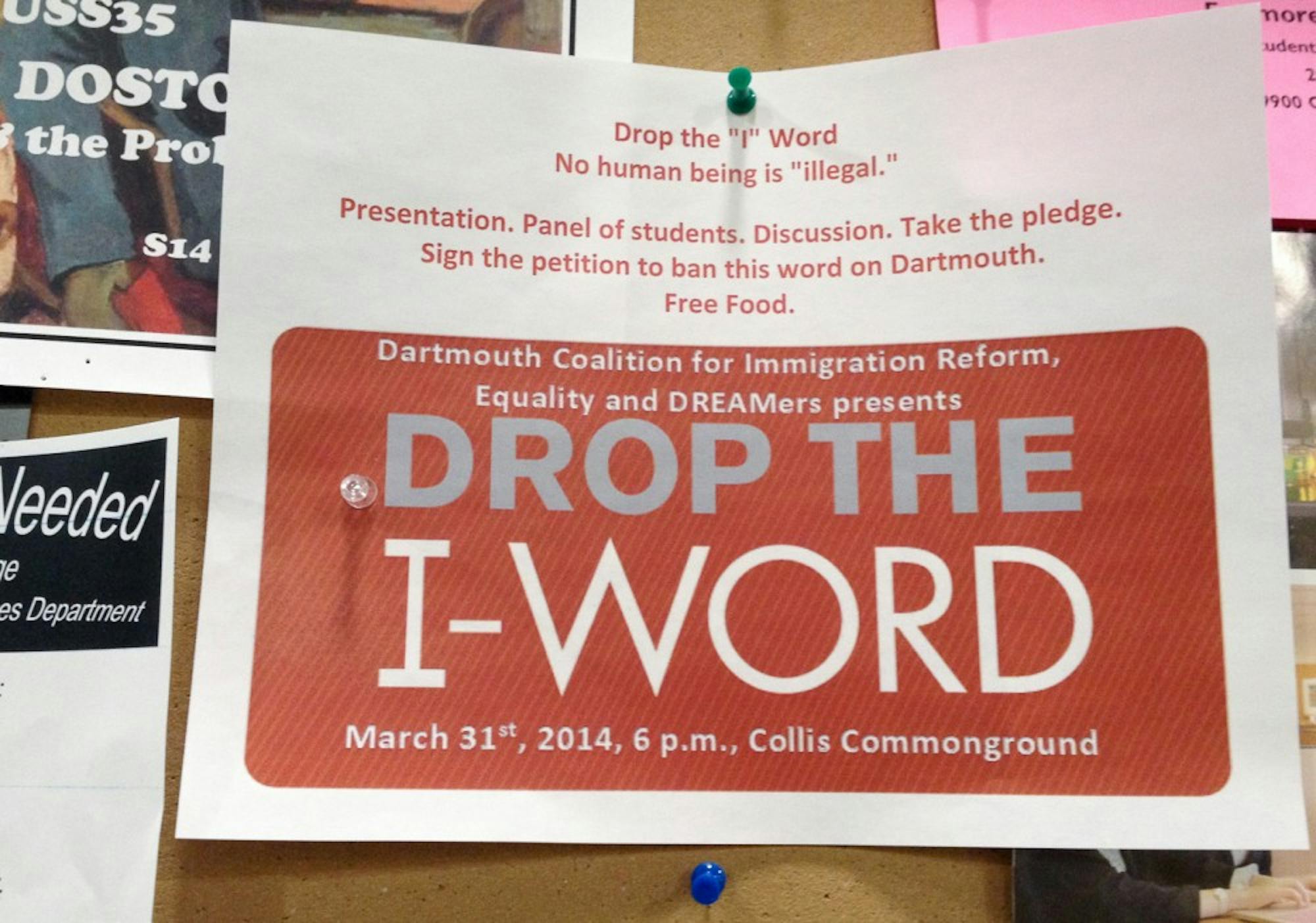

Yet this term, posters urging students to “drop the I-word” have appeared taped inside bathroom stalls and tacked to the cluttered walls of Novack Café. Meant to encourage discussion of the term “illegal immigrant,” the posters advertise an event that will take place in Collis Common Ground at 6 p.m. tonight. The Dartmouth Coalition for Immigration Reform, Equality and DREAMers, a group founded last fall, is hosting the event and will ask attendees to sign a petition that would ban the term at the College.

For some, threads of activism are weaving together at exactly the right time.

“I’m tired of not saying anything because every day it still looms over me, over my head, that I’m undocumented,” the male member of the Class of 2017 and member of CoFIRED said. “Not to be able to tell anyone is hard. I have to keep something that affects my life, that affects my family, hidden.”

“Never rested.”

Growing up, the male member of the Class of 2017 said, he and his family lived with a constant fear of deportation.

His parents continue to live with that fear. Unlike him, they are not covered by President Barack Obama’s June 2012 memorandum known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which grants renewable two-year deportation deferrals and work permits to undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children and meet other criteria like obtaining a high school diploma.

For his parents, deportation remains a threat. An estimated 400,000 undocumented immigrants per year were deported from 2009 through 2012, according to the Pew Research Center. In 2010, 1 million undocumented children were living in the U.S., as were 4.5 million children born in the U.S. to undocumented parents.

“Some students don’t know, their parents haven’t told them, until they graduate from high school or they go try and get a driver’s license, that they’re unauthorized to be here,” Wright said.

A female member of the Class of 2012, who is undocumented and asked to remain anonymous to preserve her privacy, said that fear and stress are part of her family’s daily life.

When her family left Eastern Europe for Connecticut in 2002, they packed up and shipped their belongings to the U.S. in three days, not telling anyone where they were going. Unable to contact anyone from home, they lost touch with many friends.

“Mentally speaking, you are never rested,” she said. “You are living with the fear of what is going to happen.”

Thinking of families being torn apart stirred a visceral reaction in the male member of the Class of 2017.

“You feel angry at something,” he said. “You feel angry at the system.”

“This whole other set of things.”

Valedictorian of her high school class, the female member of the Class of 2012 said she was rejected by most universities she applied to because of her immigration status, leaving her without college plans.

The day after her high school graduation, she heard the phone ring in her Connecticut condominium. A voice on the line told her she had been accepted to Dartmouth.

“Everything around me just stopped,” she said. “I feel like that moment was savored forever.”

Since undocumented students are ineligible for federal aid, when allocating financial aid, the College reviews them as international applicants and meets their demonstrated need through institutional scholarships and loans, dean of admissions and financial aid Maria Laskaris said.

Only a few other institutions currently offer need-blind admission to and meet the full demonstrated financial need of non-American citizens, including Princeton University, Harvard University, Yale University, The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Amherst College.

OVIS provides information, resources and confidential counseling to undocumented students who have questions or seek support. OVIS also works with a law firm in Boston that provides pro-bono legal help to students on an individual basis, director Susan Ellison said.

The female member of the Class of 2012 said that the firm assisted her after her father was deported, as she had concerns about her own status.

Yet legal barriers can prevent matriculated undocumented students from pursuing some College offerings.

Since traveling abroad would require a passport, for example, undocumented students cannot attend foreign study programs and language study abroad programs and can feel isolated from documented peers.

Davis said undocumented students he has worked with are sometimes unsure how to do some things, like return home over break, that documented students don’t think twice about. They may avoid trains or buses that pass too closely to a border, he said, out of fear that a law official could board and ask to see passengers’ identification.

While the students Davis speaks with have not identified being undocumented as a detriment to their social lives, he said, “intersecting identities” connected to their immigration status, including socioeconomic background and ethnicity, do play a role.

“Many of them, not all, are also from under-resourced backgrounds financially,” he said. “They have this whole other set of things that some other, documented students have, which is trying to work enough hours to pay for what they need.”

Pelaez said that the politically aware nature of the Dartmouth student body made it a more accepting community than the neighborhood where she lives in the U.S., adding that she has never received criticism from her peers at Dartmouth because of her immigration status.

The female member of the Class of 2012 agreed, saying that personal problems, like her father’s deportation, affected her academic life, but her friends “did the best they could” to support her.

“My experience at Dartmouth was great,” she said. “I had my own personal stress of being undocumented in general, but there was no added stress because of Dartmouth in any way.”

The male member of the Class of 2017 said he established a network of allies comprising friends and professors, especially those in the Latin American, Latino and Caribbean studies department.

Recalling his frustration when his seventh grade history class skipped its textbook’s chapter on the Mexican-American War, he said he now takes LALACS courses to illuminate the history he was never taught.

Some students’ undocumented status also requires them to think strategically about future employment.

While the female member of the Class of 2012 was in limbo for approximately six months after graduation, she found a job and now works as an analyst in the music industry. DACA, which came into effect shortly after her graduation, allowed her to obtain the documents necessary for formal employment.

“A piece of paper is your passport to anything you want to do in the United States,” she said.

Currently, those who qualify for DACA can continually renew their deferral every two years, though the executive order’s future depends on the next president.

“Time to stop being invisible.”

Some undocumented students and allies have started to vocally advocate for stronger resources at the College. CoFIRED members drafted portions of the “Freedom Budget” demanding more support for undocumented students. Demands include increasing outreach to prospective undocumented students, considering applicants in the domestic admission pool and creating an academic class that highlights the undocumented immigrant experience in America.

“It’s time to stop being invisible, stop being in the shadows and at least get something done and make Dartmouth acknowledge our existence,” the male member of the Class of 2017 said. “All they do is accept us, and then they just throw us in here and that’s it.”

Pelaez said that while she has found the Office of Pluralism and Leadership, the Financial Aid Office and programs like FYSEP helpful when she had a question or concern, resources are decentralized, and students often struggle to determine who they should contact when they need help.

Latino studies and anthropology professor Lourdes Gutiérrez, who is conducting research on the undocumented student experience with Institute of Writing and Rhetoric professor Claudia Anguiano, said that part of their goal is to understand how institutions can better support undocumented students.

“For me,” Gutiérrez said, “institutional support begins with acknowledgement that they are here and that they need to be better served.”

Davis emphasized that it is important to acknowledge the work that is done for undocumented students on campus, but it is still necessary to approach the issue strategically and proactively.

“I think there really is a commitment here to them having a good experience, a wonderful experience,” Davis said. “Yet quiet students who might not seek out and self-advocate for themselves are less likely to be aware of those resources.”

Dartmouth, said the male member of the Class of 2017, must do more to support undocumented students. A member of CoFIRED, he said he urges a culture of understanding and empathy toward undocumented families.

These families, he said, take on incredible risk to come to the U.S.

“Nobody leaves their home just at a whim,” he said. “Nobody leaves their family, nobody risks death, nobody wants to die to cross that border. They do it out of love. They do it for their family because they have nothing else.”

This article was initially printed on March 31, 2014 under the headline "'Never Rested': A look at Dartmouth's undocumented students."