After 16 years as a history professor at Dartmouth, Judith Byfield ’80 left her tenured position and title as chair of the women’s and gender studies department in 2007 to teach at Cornell University.

A black scholar of Africanism, Byfield said she felt isolated at the College, citing a lack of an intellectual community for her specific field and a clear absence of a community among her minority colleagues.

“It’s an isolated place for faculty of color, and sometimes it’s not the easiest environment,” Byfield said. “There was part of me that was ready to try being in a slightly larger location with a little more diversity.”

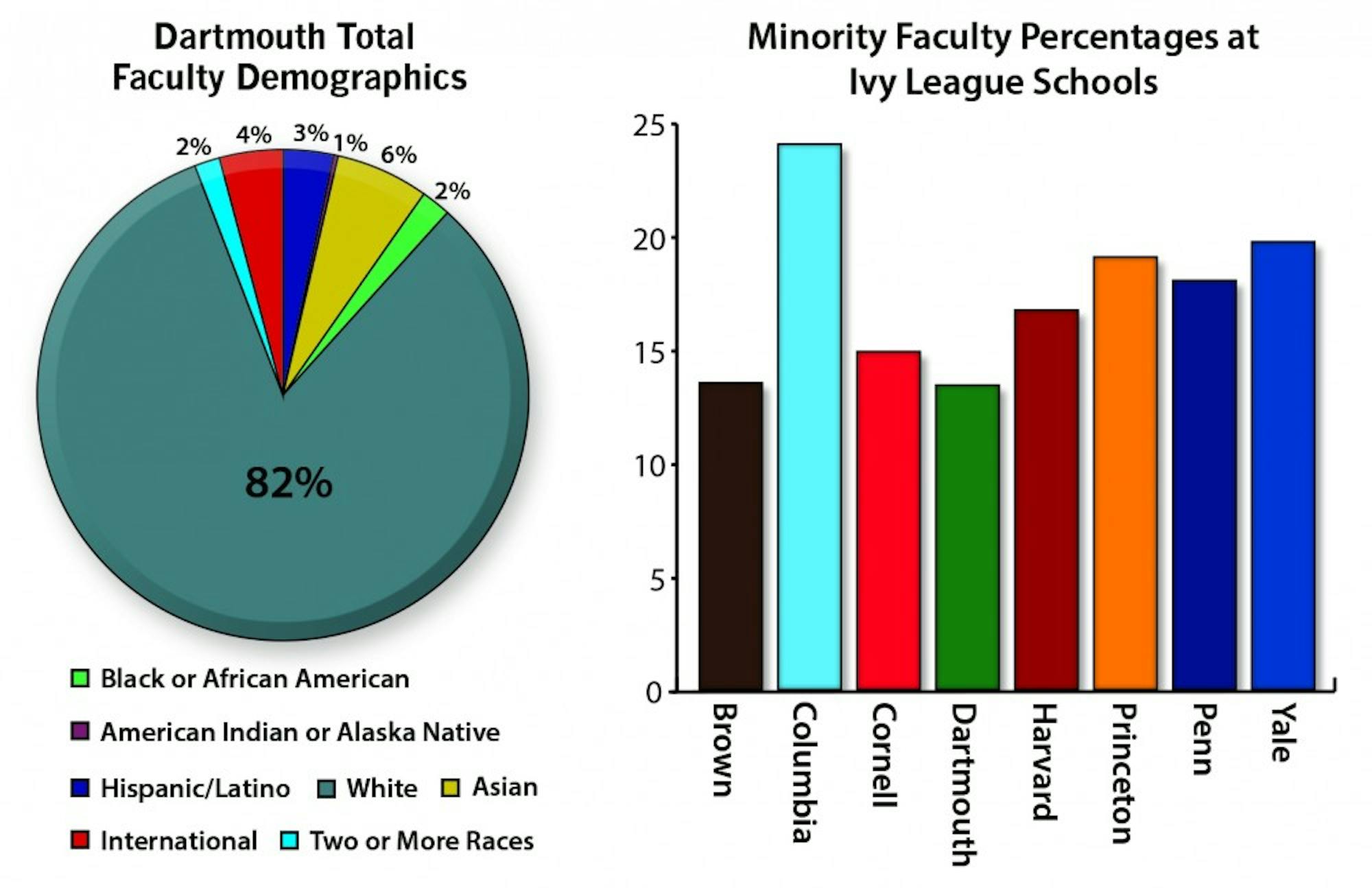

Dartmouth’s faculty is the least diverse in the Ivy League, with total white faculty at 82 percent, including the graduate schools. Approximately 2 percent of faculty members are black, and 3 percent are Hispanic/Latino. Roughly 0.4 percent of faculty, or five professors, are Native American — a relatively high number among Ivy League institutions, according to the 2012 Dartmouth Fact Book.

Of the current undergraduate student body, 7 percent are black, 7 percent are Hispanic/Latino and 3 percent are Native American.

Several black professors point to the poor retention of underrepresented minority faculty, and many tenured minority faculty members have left Dartmouth for other institutions over the past decade. History professor Craig Wilder left after six years to teach at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and history and Africana studies Celia Naylor left a tenured position to move to Barnard College.

At the surface, much of this could be attributed to the College’s small size and rural setting, but some professors point to deeper institutional problems that exacerbate the recruitment and retention of minority professors.

“The issue of minority recruitment goes beyond the oft-cited fact that Dartmouth is located in a rural and largely white community,” mathematics professor Craig Sutton, one of nine tenured black faculty members at Dartmouth, said in an email. “Since I’m aware of faculty of color who have left or would leave Dartmouth for other similarly situated institutions, it’s clear that more than regional demographics is at play.”

About 78 percent of Hanover residents are white, according to the 2010 Census. Sutton said that Hanover’s image as being “largely white and rural” has often been used as an excuse to avoid asking harder, institutional questions about recruitment and retention.

Dean of the Faculty Michael Mastanduno paints a different picture, attributing the low number of underrepresented minority faculty as a side effect of a larger supply and demand issue. Since every elite school aims to increase faculty diversity, Dartmouth is in constant competition with peer institutions to retain and recruit high-quality minority faculty members. The so-called “poaching” of minority faculty is one posited reason for a very mobile group of professors of color.

“We are a very good environment for assistant professors, and they flourish, and when they get tenure or before they get tenure, they’re very attractive,” Mastanduno said. “We can compete on a lot of different dimensions but there are some that boil down to life preferences.”

Mastanduno reiterated Dartmouth’s commitment to creating and maintaining a diverse faculty. The school “does everything it can” to match salary, offer research support and professional development and accommodate spouses, he said.

“We are very aggressive but it’s a tough game,” Mastanduno said. “You can’t bat .500 or .800 in a game like this.”

Though some professors suggested Dartmouth does not fight hard enough for minority faculty who are contemplating the switch to another school, Byfield said she does not see this pattern, adding that the College often does not fight hard to keep white professors. The fervor with which the school hopes to keep a professor usually depends on their field of work.

She suggested that Dartmouth conduct exit interviews with departing faculty members, but acknowledged the difficulty of the proposal.

“Sometimes not cultivating the data allows you to not address the problem,” she said. “Invariably people who decide to leave will leave for a number of reasons, but some are deeply imbedded in structure and culture of university.”

Many faculty members of color voiced concerns that minority faculty members are starkly absent from elevated and decision-making positions. Stephon Alexander, a tenured professor in the physics and astronomy department, said faculty of color need to be given a stronger voice in the recruiting process, and that the College must also commit towards giving current minority faculty members a reason to stay.

“We shouldn’t wait until someone gets offered a job to try to recruit them here. Because the issue is so dire, when it comes to hiring faculty of color, it should be more active,” Alexander said. “The important thing here is that to retain [minority faculty], we should feel that we have a voice in the recruitment process itself — we feel we can add value to ensure that the hiring process is actively seeking faculty of color.”

The struggles accompanying minority recruitment and retention are not unique to Dartmouth. Frank Wilderson ’78, a drama and African-American studies professor at the University of California, Irvine, said many universities seem to lose their minority professors in their sixth or seventh years.

“Irvine is not doing a good job,” Wilderson said. “The only difference is that the UC system is more transparent than the Ivy League. But I don’t think there’s a good job happening. I think that no institution is really doing a good job.”

Alexander said that a clear effort by the College to mitigate its recruitment problems is essential in retaining current faculty members, and added that the perceived trend of faculty leaving Dartmouth further exacerbates efforts to recruit.

“If I say it’s important to bring in minority faculty in the sciences, and find the College doesn’t have the same volition, it makes it hard for me to remain here if other opportunities come knocking, if those institutions have more volition,” Alexander said.

Part of Dartmouth’s existing recruitment problem may lie in its own history. Wilderson said that due to an aggressive political climate in the 1970s and 1980s, the College was actively against the recruitment of minority faculty.

Those outside the College have consistently cited Dartmouth’s reputation as an “old white boy’s club.” In August, Boston Globe writer Derrick Jackson called Dartmouth a school that “far too often seems to exist solely to reveal the depths of racial catatonia among cloistered white students.” In 1989, racial tension at the College came to national attention when staff members of The Dartmouth Review had a verbal confrontation with Bill Cole, a black music professor, in the classroom. The Review had previously attacked Cole in its pages.

Byfield said that during her years at the College, she often had black students come into her office seeking guidance after insensitive incidents involving the Review and racially-themed fraternity parties.

“So often there wasn’t any thought toward the implications on how it would affect students on campus or faculty,” Byfield said. “I met with multiple students trying to get them to stay focused and remind them what they’re here for and not to get derailed by these sorts of incidents. But it’s time-consuming.”

Beyond existing institutional problems, the College’s rural location plays a major part in why minority professors are lukewarm about coming to Dartmouth, Alexander said. He said that the College must be proactive in its endeavors to support current faculty of color because both current and prospective faculty members rely on a strong minority community. Hanover, whose black population is just 4 percent, impacts the social climate for many faculty of color.

“I rely that much more on Craig Sutton being here than if I was at NYU,” Alexander said. “It matters to me that he’s a colleague, so on one of these dark and lonely nights we can go get dinner and talk. It’s intellectual as well as social — these things are imbued with each other for a young academic.”

Russell Rickford, a black tenure-track faculty member who is leaving this year to teach history at Cornell, said that large-scale changes must be made on the part of the College, and suggested the creation of a center for race, class and social justice.

“There needs to be a push for broad transformation, not just more concern for ‘numbers’ relative to ‘peer institutions,’ no matter how marginal those numbers may be,” Rickford said. “Incrementalism isn’t working. It’s not just a question of retention. It’s a question of thriving. How do we begin to transform Dartmouth into a place where people of color, working-class people, LGBTQ people actually thrive?”

This article has been updated to reflect the following correction:

Correction: Nov. 14, 2013

The original version of this article incorrectly described Rickford's position. He is a tenure-track professor, not an untenured professor.