As Dartmouth welcomes prospective students to campus, tour guides boast that the College’s graduation rates are among the highest in the country. In 2012, the numbers backed up the claim: according to the latest report from the Education Department, 96 percent of Dartmouth students graduate within six years.

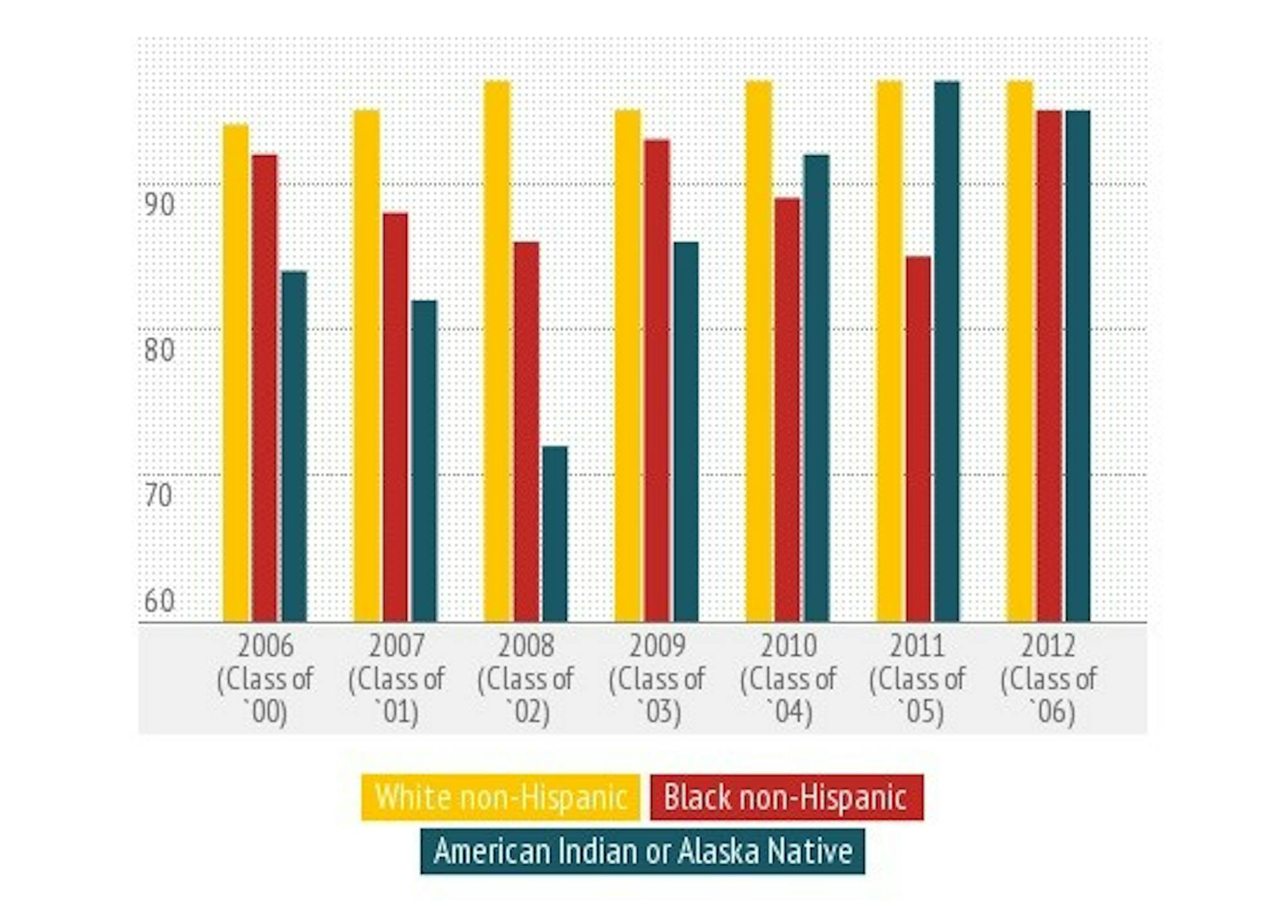

But the graduation is not consistent across all races. While numbers have fluctuated, over the past several years, black and Native American students have graduated at lower rates than white students.

Since 2006, an average of 90 percent of black students, 93 percent of Hispanic students and 83 percent of Native American students graduated within six years from each class. An average of 96 percent of white students graduated in the same time frame.

By 2012, 97 percent of white students, 95 percent of black students, 93 percent of Hispanic students and 86 percent of Native American students from the Class of 2010 had graduated. For black students, 2012 marked a 12 percent increase in graduation rates from 2011, when 85 percent of black students graduated.

For Native American students, however, graduation rates in 2012 were the lowest since 2007. Just 82 percent of Native American students from the class of 2005 had graduated by 2007.

The six-year graduation rate of Hispanic students has remained above 90 percent since 2006, topping out at 96 percent in 2011. In 2011, Dartmouth’s graduation rate for black students was the lowest in the Ivy League. According to the National Journal, which compiled data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the six-year graduation rates for black students at Columbia University, Harvard University, Princeton University and Stanford University were higher than the College’s 85 percent graduation rate in 2011, the last year data was available for all institutions. At Columbia, the six-year graduation rate for black students was 91 percent in 2011, while at Harvard and Princeton, 94 percent of black students graduated within the six year window. Similarly, Stanford graduated 93 percent of its black students.

The University of Chicago graduated a lower rate of black students than Dartmouth that year. Just 80 percent of black students at the University of Chicago received their diplomas.

Among the same schools, Dartmouth had the highest graduation rate for Hispanic students.

Sociology professor Janice McCabe said that without data points continuously marking an upward trend in closing the gap, it is premature to attribute the increase in graduation rates for students of color to administrative action. A third year with an upward trend, or at least year-to-year consistency, would more clearly point to any success.

Dartmouth’s rates are extremely high by the standard of graduation rates across the country, said Matthew Chingos, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on Education Policy. Chingos emphasized that because minorities make up a relatively small share of the population, yearly percentages may oscillate.

Associate dean for student academic support services Inge-Lise Ameer pointed to the First-Year Student Enrichment Program, First Generation Network, Academic Skills Center and the Undergraduate Deans Office’s philosophy of reaching out to students as initiatives that have helped close the gap.

“[Dean of the College Charlotte] Johnson and [Dean of the Faculty Michael] Mastanduno feel really strongly that academic success, not just getting by, but academic success is a really important factor for all students at Dartmouth College,” Ameer said.

College spokesman Justin Anderson said FYSEP and the Advising 360 programs are evidence of progress in closing the graduation gap.

The College found that students who went through FYSEP had a higher GPA than those who did not, Anderson said.

FYSEP, the Academic Skills Center and Advising 360 are available to all students, regardless of race or cultural background.

With the lack of consistency in graduation rates, some community members remain skeptical of Dartmouth’s commitment to minority students. Students and faculty suggested that a variety of factors contribute to the lack of consistent graduation rates for students of color.

Community members said both educational disparities and financial hardships contribute to racial inequality in graduation rates.

Because the United States’ public school system is funded by property taxes, poor neighborhoods have, on balance, weaker educational opportunities when compared with wealthier districts, sociology professor Emily Walton said. Research indicates that black families have fewer assets than white families, even controlling for incomes. As a result, black families are more likely to live in neighborhoods with weaker education systems, and structural factors are to blame for poorer educational preparation for minority students even before they arrive at Dartmouth, Walton said.

Chingos echoed these sentiments.

“One explanation that is clearly important in general is differences in levels of academic preparation,” he said. “We know that, on average, minority students come from families with lower incomes and less wealth than white families. They attend elementary and secondary schools that aren’t as good, so as a result, they tend to arrive at college with weaker preparation on average.”

Differences in preparation do not entirely explain all the graduation rate discrepancies at U.S. institutions, but it certainly contributes, he added.

Aaron Colston ’14 hedged against detractors of affirmative action, arguing that if the students are accepted, they are capable of succeeding at the College.

“My personal stance is that students of color at Dartmouth are perfectly prepared to be here if they are admitted,” Colston said. “When you admit the student you are saying that they are ready for this institution. It’s the institution which is not ready and the institution which is not prepared.”

Public policy professor Charles Wheelan agreed that academic preparation influences the graduation gap, noting that if the median SAT scores are lower for black students than white students, then it should be “no shock” that students from different racial groups bring different academic skills. He said taking a better look into the numbers and determining why lower rates exist at all will help further the discussion.

“What’s the difference between the 10 percent [of black students] who don’t make it and the 90 percent who do?” he said. “Are those 10 percent in the bottom tail? Did they have lower GPAs and test scores coming in? Or maybe that’s not the case at all. Did they come from less rigorous high schools?”

Wheelan said analyzing graduation gaps without regard to race in particular may yield results that can be applied to more specific populations of students.

“What do the 3 percent of white students who don’t graduate look like? Do they have anything in common with the 10 percent of black students?” he said. “I want to know why anybody isn’t making it through, and then I want to drill down what the differences might be between the two groups.”

Wheelan said a broader look at the big issue, from the goals of Dartmouth’s diversity program to the smallest differences among racial groups, would be beneficial.

Minority faculty retention may also contribute to the graduation gap, community members said. At Dartmouth, black faculty make up only 2 percent of the total while Native Americans make up less than 1 percent — only five professors at the College are Native American.

These numbers are in line with other those of Ivy League institutions, although in 2011, Dartmouth had the highest percentage of white faculty members in the Ivy League. In 2012, Columbia University launched a $30 million initiative to boost faculty diversity.

Walton said the College should recruit and retain minority faculty, who might then serve as mentors to students with similar backgrounds. She suggested that Dartmouth create more inclusive classrooms for students of color.

“[Minority students] should be able to talk things through about their experiences,” she said. “When you have such a difference between the student body and the faculty in terms of racial make-up, it makes it hard for students to see themselves in the position of the faculty or their professors in the classroom.”

Although Dartmouth struggles to attract minority faculty because of the Upper Valley’s lack of diversity and isolation, building a “critical mass” of faculty of color will encourage other scholars to come to Hanover, Walton said.

Some students of color support Walton’s contention. Colston said this “critical mass” of minority faculty does not exist.

“Dartmouth doesn’t have enough minority faculty in an undergraduate-focused institution to provide the examples needed for African-Americans to persist at the same rates that whites do,” Colston said. “There’s just a clear disproportion of benefit.”

Others, including Women of Color Collective vice president Yomalis Rosario ’15, pointed to Dartmouth’s structure and its disproportionate effect on students as a possible explanation for the graduation gap.

“The College predominantly serves white people of a certain class,” Rosario said. “Students of color, all marginalized communities that don’t fit the communities that this institution was made for, they face certain challenges on this campus. That can mean having to take on home burdens — financial. It can mean facing discrimination, facing overt racism and the subtle things as well.”

Although all members of the Dartmouth community deal with stress and personal problems, the College itself stymies minorities’ progress, Rosario said. As a result, Dartmouth has the responsibility to ensure minority students graduate, despite structural barriers preventing equal preparation.

“An important distinction to make here is that this institution contributes certain burdens to students of color rather than eliminating them,” she said. “The data speaks for itself. This institution affects students of color differently.”

History professor Russell Rickford, who will begin teaching at Cornell University next fall, said Dartmouth’s culture is plagued by inertia. Students target those who speak out against racial bias, rather than the issue itself, he said.

“When students raise criticism, as they did with the Real Talk protest last year, the outrage is very rarely against the concerns that the protesters are seeking to expose,” he said. “The outrage is channeled at the dissenters for having the audacity to dissent. I think that kind of enforced conformity is part of what preserves an environment that is deeply alienating to marginalized and historically oppressed groups.”

Students’ voices are silenced because some believe that racial inequality has been solved, he said. Once people frame political discourse and social issues around the ideal of a post-racial society, discussions about continuing inequalities are seen as illegitimate.

Along with creating an environment that encourages discourse and dissent, Walton supports a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to discriminatory incidents.

“We need to stop it in its tracks and it needs to come from the top down,” she said. “We need to have zero-tolerance saying these incidents, like racist graffiti, are absolutely not to be tolerated and these students will be expelled. We need some structural things in place that say this environment is not acceptable and not welcoming for students of color or women.”

Women of Color Collective member Anna Winham ’14 said the College should establish cultural initiatives to educate incoming freshmen about students’ different backgrounds and should require students to take courses to build cultural competency.

Palaeopitus member Malcolm Leverett ’14 said Dartmouth’s culture and academic rigor may affect minority graduation rates.

“Ideally, we’d love to see a 100 percent graduation rate but we don’t because people switch schools either because of academics, which can be challenging based on preparation, but a lot of times from what I’ve seen in my class, the fit isn’t right for them,” he said.

Most minority students come from urban and suburban environments, so coming to Hanover is a “giant leap” for some students, Leverett said.

“It’s a much smaller school. It’s tucked away in rural New Hampshire,” he said. “I’ve seen that be a problem for a lot of people.”

Anderson acknowledged that the most recent numbers suggesting an improvement in the graduation gap might be anomalous but said the administration is working to sustain an upward trend.

“I don’t know if the numbers are going to continue to trend in the right direction,” he said. “What I do know is that we’re going to continue to offer the kinds of programs that we’ve developed, and we’re going to improve upon them, and we’re going to come up with new ones,” he said. “We’re going to measure the success of the programs that we initiate, and we’re to continue the ones that succeed and scrap the ones that don’t.”

He emphasized that the administration sought to prevent the numbers from regressing to rates from previous years.

Rosario and Colston are former members of The Dartmouth staff.

Johnson was not made available to comment.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: Nov. 10, 2013

The original version of this article incorrectly stated that the six year graduation rates in 2012 were for students in the Class of 2006. In fact, the 2012 numbers corresponded to the graduation rates for the Class of 2010.