I talked to Psi U member Duncan Hall '13, who explained that these problems have been brought up and reconsidered each fall, and that the rumors about their meaning are just that false rumors. While members of Psi U may explain the real meaning behind their outfits, a symbol of unity and recognition, when asked, it is difficult to spread this message across campus.

"For those who don't talk to fraternity members, it's hard to get an updated view," Hall said. "Hearsay feeds hearsay, which feeds judgments that are uninformed."

Those most affected by the presence of Psi U's outfits are not likely to be the ones asking about their real meaning. In truth, Dartmouth does have a problem with classism a deep-seated, complex problem with no clear solution or definition.

Lisel Murdock '09, who worked as a Hopkins Center class divide' intern at Dartmouth, described classism in terms of cultural capital.

"It's this set of ideals and views and philosophies that give people social standing, like knowing what fork to use at the Hanover Inn," Murdock said.

For Taylor Payer '15, classism is the assumption that "everyone has enough money to be a certain kind of Dartmouth student, one that goes on fancy spring breaks in other countries, eats at expensive restaurants and wears J. Crew."

While programs like the First Year Student Enrichment Program and Quest Bridge Scholars, which matches low-income students with colleges and scholarship providers, offer resources for low-income students, these organizations may not reach all community members interested in discussing and addressing issues of classism.

For Hui Cheng '16, Dartmouth did not offer a space to discuss financial concerns.

"Coming in as a '16, I didn't want to self-segregate as Asian, I didn't qualify for Quest Bridge Scholars or FYSEP and I didn't feel like there was a community I could go to," Cheng said.

There are few places to discuss class on Dartmouth's campus, especially for non-minority students. Discussions within minority groups often leave out a key contingent of students at Dartmouth low-income white students.

"It's tough that it's assumed that if you are Native you are poor, but it's also good because I have a space to talk about [class], but white people don't," Payer said.

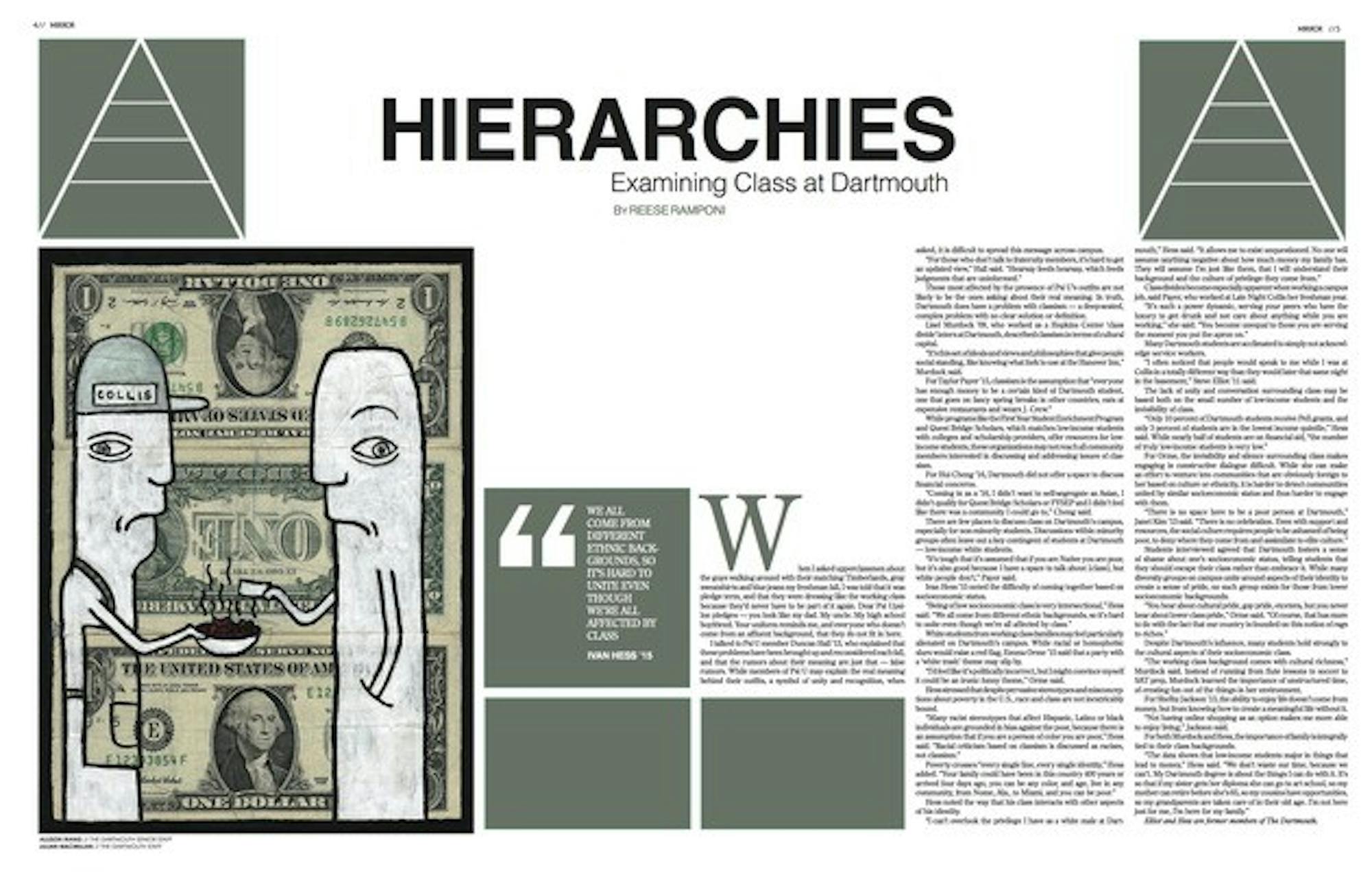

Ivan Hess '15 noted the difficulty of coming together based on socioeconomic status.

"Being of low socioeconomic class is very intersectional," Hess said. "We all come from different ethnic backgrounds, so it's hard to unite even though we're all affected by class."

White students from working class families may feel particularly alienated on Dartmouth's campus. While racial or homophobic slurs would raise a red flag, Emma Orme '15 said that a party with a white trash' theme may slip by.

"I'd feel like it's politically incorrect, but I might convince myself it could be an ironic funny theme," Orme said.

Hess stressed that despite pervasive stereotypes and misconceptions about poverty in the U.S., race and class are not inextricably bound.

"Many racist stereotypes that affect Hispanic, Latino or black individuals are grounded in bias against the poor, because there is an assumption that if you are a person of color you are poor," Hess said. "Racial criticism based on classism is discussed as racism, not classism."

Poverty crosses "every single line, every single identity," Hess added. "Your family could have been in this country 400 years or arrived four days ago, you can be any color, and age, live in any community, from Nome, Ala., to Miami, and you can be poor."

Hess noted the way that his class interacts with other aspects of his identity.

"I can't overlook the privilege I have as a white male at Dartmouth," Hess said. "It allows me to exist unquestioned. No one will assume anything negative about how much money my family has. They will assume I'm just like them, that I will understand their background and the culture of privilege they come from."

Class divides become especially apparent when working a campus job, said Payer, who worked at Late Night Collis her freshman year.

"It's such a power dynamic, serving your peers who have the luxury to get drunk and not care about anything while you are working," she said. "You become unequal to those you are serving the moment you put the apron on."

Many Dartmouth students are acclimated to simply not acknowledge service workers.

"I often noticed that people would speak to me while I was at Collis in a totally different way than they would later that same night in the basement," Steve Elliot '11 said.

The lack of unity and conversation surrounding class may be based both on the small number of low-income students and the invisibility of class.

"Only 10 percent of Dartmouth students receive Pell grants, and only 3 percent of students are in the lowest income quintile," Hess said. While nearly half of students are on financial aid, "the number of truly low-income students is very low."

For Orme, the invisibility and silence surrounding class makes engaging in constructive dialogue difficult. While she can make an effort to venture into communities that are obviously foreign to her based on culture or ethnicity, it is harder to detect communities united by similar socioeconomic status and thus harder to engage with them.

"There is no space here to be a poor person at Dartmouth," Janet Kim '13 said. "There is no celebration. Even with support and resources, the social culture requires people to be ashamed of being poor, to deny where they come from and assimilate to elite culture."

Students interviewed agreed that Dartmouth fosters a sense of shame about one's socioeconomic status, telling students that they should escape their class rather than embrace it. While many diversity groups on campus unite around aspects of their identity to create a sense of pride, no such group exists for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

"You hear about cultural pride, gay pride, etcetera, but you never hear about lower class pride," Orme said. "Of course, that has more to do with the fact that our country is founded on this notion of rags to riches."

Despite Dartmouth's influence, many students hold strongly to the cultural aspects of their socioeconomic class.

"The working class background comes with cultural richness," Murdock said. Instead of running from flute lessons to soccer to SAT prep, Murdock learned the importance of unstructured time, of creating fun out of the things in her environment.

For Shelby Jackson '13, the ability to enjoy life doesn't come from money, but from knowing how to create a meaningful life without it.

"Not having online shopping as an option makes me more able to enjoy living," Jackson said.

For both Murdock and Hess, the importance of family is integrally tied to their class backgrounds.

"The data shows that low-income students major in things that lead to money," Hess said. "We don't waste our time, because we can't. My Dartmouth degree is about the things I can do with it. It's so that if my sister gets her diploma she can go to art school, so my mother can retire before she's 65, so my cousins have opportunities, so my grandparents are taken care of in their old age. I'm not here just for me, I'm here for my family."

Elliot and Hess are former members of The Dartmouth.