"There's such an emphasis on being busy and finding satisfaction in responsibility, conversations end up being like What are you doing today?' instead of How do you feel about today?" Ali Oberg '13 said. "People want to be productive, and they don't see conversations about emotions as productive."

It's not abnormal to be sad, especially in a high-pressure atmosphere like Dartmouth, explains Paul Holtzheimer, a psychiatrist and head of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center's Mood Disorder Service. The college environment creates unrealistic expectations.

"The idea that someone can be a party animal throughout the week, still go to his 8 a.m. class and excel academically and socially is a dangerous meme," Holtzheimer said.

Karoline Walter '13 spoke about her experience balancing social and academic expectations while managing depression. "Everything is so fast paced. It's definitely easy to get lost in, and lose yourself in," Walter said.

While humans have evolved to deal with acute stress, we are more vulnerable to chronic stresses, which are more common in the college environment.

"Chronic, unpredictable stress, which defines college, is the easiest way to make a student look depressed," Holtzheimer said.

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability today, yet discussion of the issue remains scarce on campus. If we don't talk about sadness, how can we figure out when sadness is normal, and when it becomes cause for concern? Depressed feelings become abnormal when they begin to affect basic functioning. If a student isn't going to class, seeing friends or enjoying activities for an extended period of time, there may be a more serious issue.

"It's not feeling blue itself that makes you depressed, it's when the things that used to pull you out of that slump stop working," Holtzheimer said.

For those struggling with chronic depression at Dartmouth, it's much more than feeling blue. Depression is one of the most common disorders addressed by on-campus counselors, Dick's House psychiatrist Da-Shih Hu said. Despite its prevalence, the stigma around depression is not limited to this campus.

"For people that haven't had the illness or worked with people that do, they think that you can get out of bed, after all, there is nothing physically wrong with you," Holtzheimer said.

Walter agreed, saying that explaining her experience to those unfamiliar with the disorder has been difficult.

"People say, what is the problem? How can we fix it?' But there's no root to my problem. It's not just something you can identify and fix."

Often, friends who want to help aren't familiar enough with depression to notice the signs. Oberg said that while she tries to be a good resource for her friends struggling with mood disorders, the complexity of the disorder makes hard to recognize.

"I barely understand [depression], and I know people that are depressed," Oberg said. "You can get it conceptually, but you haven't experienced it."

In reality, depression is just as real as any physical disorder, a deficit in mood control no less legitimate than a deficit in physical functioning. Depression still has a negative connotation and the societal notion that one can defeat depression with mere resiliency leaves depressed individuals feeling weak-willed and flawed.

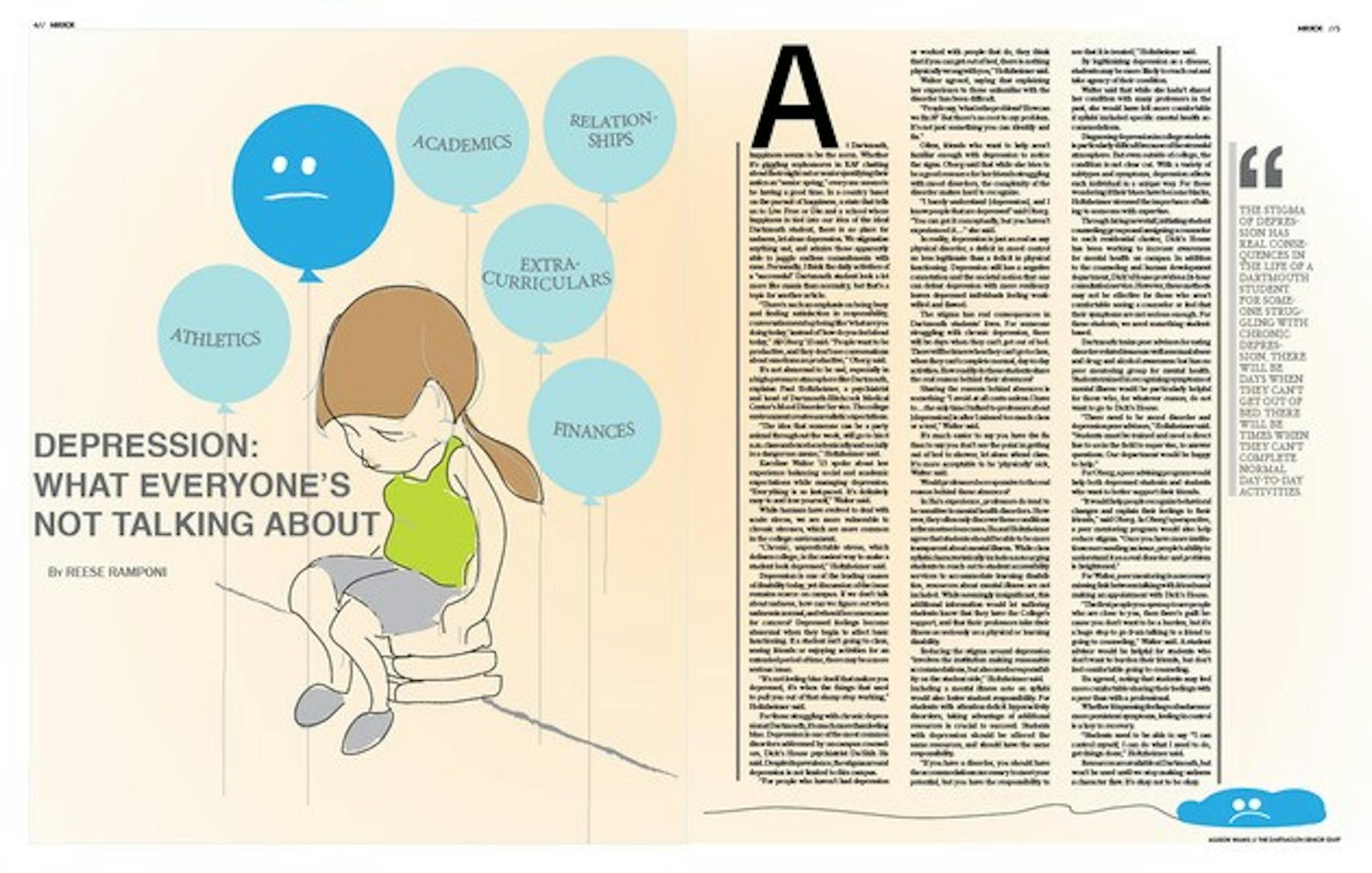

The stigma has real consequences in Dartmouth students' lives. For someone struggling with chronic depression, there will be days when they can't get out of bed. There will be times when they can't go to class, when they can't complete normal, day-to-day activities. How readily do these students share the real reason behind their absences?

Sharing the reasons behind absences is something "I avoid at all costs unless I have tothe only time I talked to professors about [depression] is after I missed too much class or a test," Walter said.

It's much easier to say you have the flu than to say you don't see the point in getting out of bed to shower, let alone attend class. It's more acceptable to be physically' sick, Walter said.

Would professors be responsive to the real reason behind these absences?

In Hu's experience, professors do tend to be sensitive to mental health disorders. However, they often only discover these conditions in the most serious cases. Hu and Holtzheimer agree that students should be able to be more transparent about mental illness. While class syllabi characteristically include a note urging students to reach out to student accessibility services to accommodate learning disabilities, resources about mental illness are not included. While seemingly insignificant, this additional information would let suffering students know that they have the College's support, and that their professors take their illness as seriously as a physical or learning disability.

Reducing the stigma around depression "involves the institution making reasonable accommodations, but also needs responsibility on the student side," Holtzheimer said. Including a mental illness note on syllabi would also foster student responsibility. For students with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders, taking advantage of additional resources is crucial to succeed. Students with depression should be offered the same resources, and should have the same responsibility.

"If you have a disorder, you should have the accommodations necessary to meet your potential, but you have the responsibility to see that it is treated," Holtzheimer said.

By legitimizing depression as a disease, students may be more likely to reach out and take agency of their condition.

Walter said that while she hadn't shared her condition with many professors in the past, she would have felt more comfortable if syllabi included specific mental health accommodations.

Diagnosing depression in college students is particularly difficult because of the stressful atmosphere. But even outside of college, the condition is not clear cut. With a variety of subtypes and symptoms, depression affects each individual in a unique way. For those wondering if their blues have become blacks, Holtzheimer stressed the importance of talking to someone with expertise.

Through hiring new staff, initiating student counseling groups and assigning a counselor to each residential cluster, Dick's House has been working to increase awareness for mental health on campus. In addition to the counseling and human development department, Dick's House provides a 24-hour consultation service. However, these methods may not be effective for those who aren't comfortable seeing a counselor or feel that their symptoms are not serious enough. For these students, we need something student-based.

Dartmouth trains peer advisors for eating disorder-related issues as well as sexual abuse and drug and alcohol awareness but has no peer mentoring group for mental health. Students trained in recognizing symptoms of mental illness would be particularly helpful for those who, for whatever reason, do not want to go to Dick's House.

"There need to be mood disorder and depression peer advisors," Holtzheimer said. "Students must be trained and need a direct line to us in the field to supervise, to answer questions. Our department would be happy to help."

For Oberg, a peer advising program would help both depressed students and students who want to better support their friends.

"It would help people recognize behavioral changes and explain their feelings to their friends," Oberg said. In Oberg's perspective, a peer mentoring program would also help reduce stigma. "Once you have more institutions surrounding an issue, people's ability to understand it as a real disorder and problem is heightened."

For Walter, peer mentoring is a necessary missing link between talking with friends and making an appointment with Dick's House.

"The first people you open up to are people who are close to you, then there's guilt because you don't want to be a burden, but it's a huge step to go from talking to a friend to going to counseling," Walter said. A student advisor would be helpful for students who don't want to burden their friends, but don't feel comfortable going to counseling.

Hu agreed, noting that students may feel more comfortable sharing their feelings with a peer than with a professional.

Whether it is passing feelings of sadness or more persistent symptoms, feeling in control is a key to recovery.

"Students need to be able to say I can control myself, I can do what I need to do, get things done,'" Holtzheimer said.

Resources are available at Dartmouth, but won't be used until we stop making sadness a character flaw. It's okay not to be okay.