"Nothing daunted me," Kurtz said. "It was difficult because there was resistance, but it was inevitable that we were going to have teams here. Dartmouth had admitted women and had committed to treating women the same as they treated men. It's just that it took a while to work our way through various attitudes."

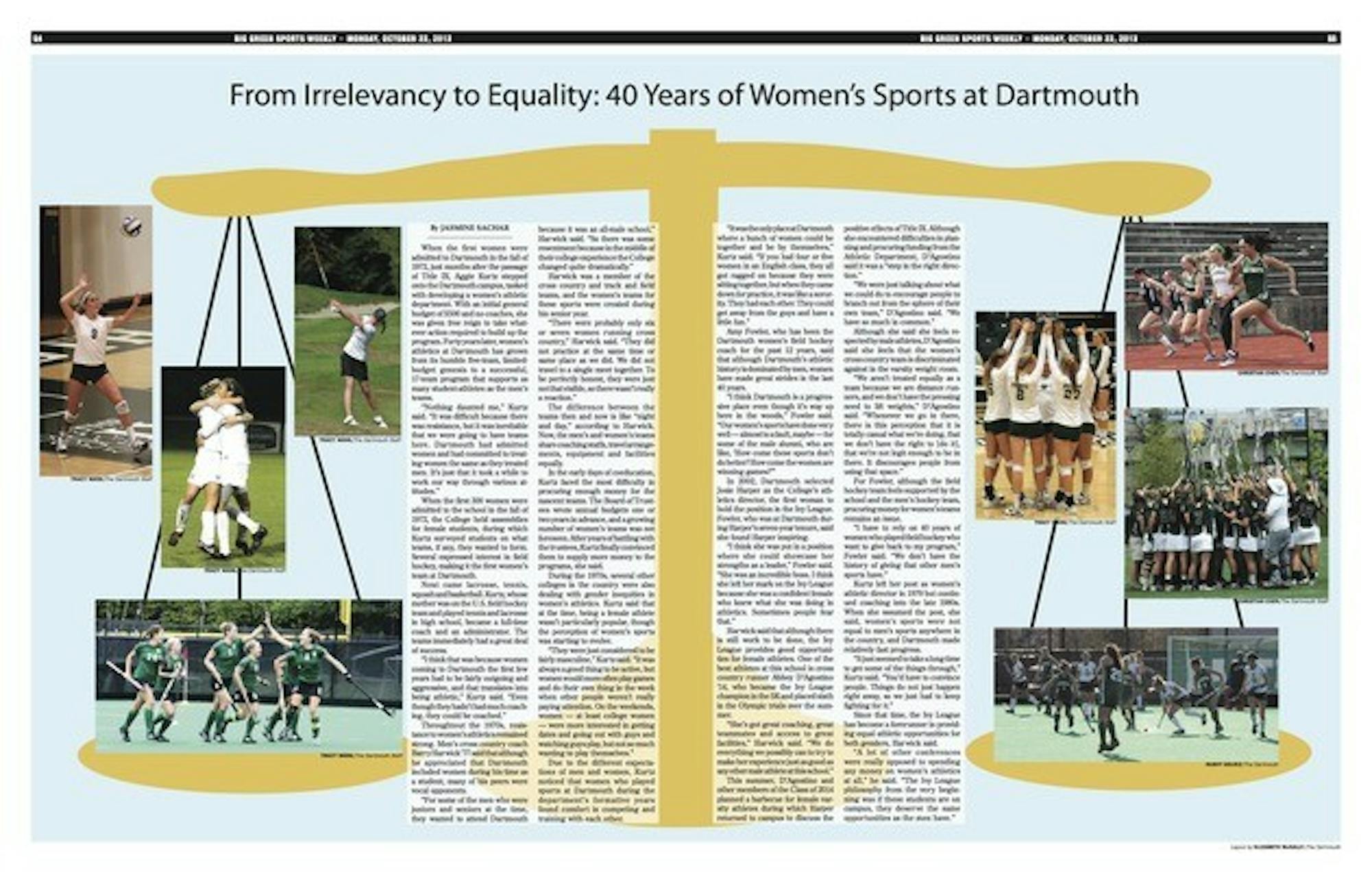

When the first 300 women were admitted to the school in the fall of 1972, the College held assemblies for female students, during which Kurtz surveyed students on what teams, if any, they wanted to form. Several expressed interest in field hockey, making it the first women's team at Dartmouth.

Next came lacrosse, tennis, squash and basketball. Kurtz, whose mother was on the U.S. field hockey team and played tennis and lacrosse in high school, became a full-time coach and an administrator. The teams immediately had a great deal of success.

"I think that was because women coming to Dartmouth the first few years had to be fairly outgoing and aggressive, and that translates into being athletic," Kurtz said. "Even though they hadn't had much coaching, they could be coached."

Throughtout the 1970s, resistance to women's athletics remained strong. Men's cross country coach Barry Harwick '77 said that although he appreciated that Dartmouth included women during his time as a student, many of his peers were vocal opponents.

"For some of the men who were juniors and seniors at the time, they wanted to attend Dartmouth because it was an all-male school," Harwick said. "So there was some resentment because in the middle of their college experience the College changed quite dramatically."

Harwick was a member of the cross country and track and field teams, and the women's teams for these sports were created during his senior year.

"There were probably only six or seven women running cross country," Harwick said. "They did not practice at the same time or same place as we did. We did not travel to a single meet together. To be perfectly honest, they were just not that visible, so there wasn't really a reaction."

The difference between the teams then and now is like "night and day," according to Harwick. Now, the men's and women's teams share coaching staffs, travel arrangements, equipment and facilities equally.

In the early days of coeducation, Kurtz faced the most difficulty in procuring enough money for the nascent teams. The Board of Trustees wrote annual budgets one or two years in advance, and a growing number of women's teams was not foreseen. After years of battling with the trustees, Kurtz finally convinced them to supply more money to the programs, she said.

During the 1970s, several other colleges in the country were also dealing with gender inequities in women's athletics. Kurtz said that at the time, being a female athlete wasn't particularly popular, though the perception of women's sports was starting to evolve.

"They were just considered to be fairly masculine," Kurtz said. "It was always a good thing to be active, but women would more often play games and do their own thing in the week when other people weren't really paying attention. On the weekends, women at least college women were more interested in getting dates and going out with guys and watching guys play, but not so much wanting to play themselves."

Due to the different expectations of men and women, Kurtz noticed that women who played sports at Dartmouth during the department's formative years found comfort in competing and training with each other.

"It was the only place at Dartmouth where a bunch of women could be together and be by themselves," Kurtz said. "If you had four or five women in an English class, they all got ragged on because they were sitting together, but when they came down for practice, it was like a sorority. They had each other. They could get away from the guys and have a little fun."

Amy Fowler, who has been the Dartmouth women's field hockey coach for the past 12 years, said that although Dartmouth's athletic history is dominated by men, women have made great strides in the last 40 years.

"I think Dartmouth is a progressive place even though it's way up here in the woods," Fowler said. "Our women's sports have done very well almost to a fault, maybe for some of the male alumni, who are like, How come these sports don't do better? How come the women are winning games?'"

In 2002, Dartmouth selected Josie Harper as the College's athletics director, the first woman to hold the position in the Ivy League. Fowler, who was at Dartmouth during Harper's seven-year tenure, said she found Harper inspiring.

"I think she was put in a position where she could showcase her strengths as a leader," Fowler said. "She was an incredible boss. I think she left her mark on the Ivy League because she was a confident female who knew what she was doing in athletics. Sometimes people fear that."

Harwick said that although there is still work to be done, the Ivy League provides good opportunities for female athletes. One of the best athletes at this school is cross country runner Abbey D'Agostino '14, who became the Ivy League champion in the 5K and placed sixth in the Olympic trials over the summer.

"She's got great coaching, great teammates and access to great facilities," Harwick said. "We do everything we possibly can to try to make her experience just as good as any other male athlete at this school."

This summer, D'Agostino and other members of the Class of 2014 planned a barbecue for female varsity athletes during which Harper returned to campus to discuss the positive effects of Title IX. Although she encountered difficulties in planning and procuring funding from the Athletic Department, D'Agostino said it was a "step in the right direction."

"We were just talking about what we could do to encourage people to branch out from the sphere of their own team," D'Agostino said. "We have so much in common."

Although she said she feels respected by male athletes, D'Agostino said she feels that the women's cross country team is discriminated against in the varsity weight room.

"We aren't treated equally as a team because we are distance runners, and we don't have the pressing need to lift weights," D'Agostino said. "Whenever we go in there, there is this perception that it is totally casual what we're doing, that we don't have the right to [do it], that we're not legit enough to be in there. It discourages people from using that space."

For Fowler, although the field hockey team feels supported by the school and the men's hockey team, procuring money for women's teams remains an issue.

"I have to rely on 40 years of women who played field hockey who want to give back to my program," Fowler said. "We don't have the history of giving that other men's sports have."

Kurtz left her post as women's athletic director in 1979 but continued coaching into the late 1980s. When she sssumed the post, she said, women's sports were not equal to men's sports anywhere in the country, and Dartmouth made relatively fast progress.

"It just seemed to take a long time to get some of the things through," Kurtz said. "You'd have to convince people. Things do not just happen right away, so we just had to keep fighting for it."

Since that time, the Ivy League has become a forerunner in providing equal athletic opportunities for both genders, Harwick said.

"A lot of other conferences were really opposed to spending any money on women's athletics at all," he said. "The Ivy League philosophy from the very beginning was if these students are on campus, they deserve the same opportunities as the men have."